Graphic by Maralmaa Munkh-Achit

Written by Noah Yosif

Edited by Sonali Uppal

Introduction

The global coronavirus recession prompted most countries to enact a historic amalgam of economic policies designed to mitigate its financial disruption to households, businesses, as well as their economy at-large. These measures encompassed direct payments to citizens, government guarantees to eligible businesses, significant reductions to central bank interest rates, enhanced macroprudential policies toward private financial institutions, as well as a general expansion of the social safety net such as increased unemployment benefits[1]. While most experts concur these measures were necessitated by the opportunity cost of inaction, their enlargement of government debt balances and central bank liquidity have indubitably contributed to a rise in global inflation, as well as concerns of increased volatility in global prices and purchasing power. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), average annual global inflation stood at 3.3 percent in April 2021, up 37.5 percent since the previous month, at a level not seen since October 2008 during the Great Recession[2].

This predictable surge in global inflation has triggered a major debate among economists and policymakers alike regarding its future trajectory, as either a transient phenomenon, destined to subside over time in a post-coronavirus economy, or a sustained adjustment, with significant implications for consumers and businesses. Yet, absent from this discussion, is acknowledgment of the increased dissociation between inflation and the money supply, as well as the confluence of structural drivers including aging demographics, productivity growth, and entrenched inflation expectations on this relationship. In fact, despite similar pronouncements of surging inflationary pressures following countries’ enactment of economic stimuli during the 2001 Recession[3], Great Recession of 2008[4], and European Debt Crisis of 2010[5], global inflation remained mulishly low, and well beneath central bank targets. Understanding the recent divergence between inflation and the money supply will yield essential insight to the trajectory of global inflation in the aftermath of the coronavirus recession, as well as its impact on the international economy at-large.

The Evolution of Classical Inflation

While the latest trends cast doubt on a sustained period of global inflation, such concerns are well-founded in classical macroeconomic theory, suggesting that an enlarged money supply accelerates credit demand and, in turn, generates increased consumption of goods and services accompanied by rising prices absent any counteractive changes to supply[6]. Given such dynamics, which have, until recently, proven historically accurate, increased government debt via economic stimuli enacted in response to the coronavirus recession could be considered quite pernicious as higher debt levels raise concerns of repayment risks to the borrowing country, which could foster downward pressure on its currency and, in turn, bolster inflation expectations[7]. In this scenario, borrowing countries would be limited in their responses to restore sustainability: promote fiscal austerity, induce faster economic growth, or lower real interest rates; if these options were either insufficient or infeasible, an enlarged yet stagnant money supply could yield increased inflation requiring even more drastic policy responses to maintain price stability[8].

However, shifting macroeconomic dynamics have limited the applicability of these once-sound theoretical constraints. Advanced economies as well as some emerging market economies have exhibited an increased tolerance for managing higher levels of sovereign debt at lower real interest rates with reduced risk premiums, leading to less-binding sustainability limitations and muted inflation risks[9]. Additionally, many central banks have become increasingly amenable to accumulating additional government debt on their balance sheets to finance essential stimulus efforts and anchor inflation expectations[10]. Furthermore, many of these same central banks have been operating near or at the zero-bound since the aftermath of the Great Recession, which has amplified the potential for disinflation and, consequently, lowered inflation expectations[11]. These trends, which emerged well before the coronavirus recession, have provided most countries with considerable freedom to enact broad-based economic stimulus measures with limited concern for their well-documented consequences on global inflation.

Divorcing the Money Supply from Inflation

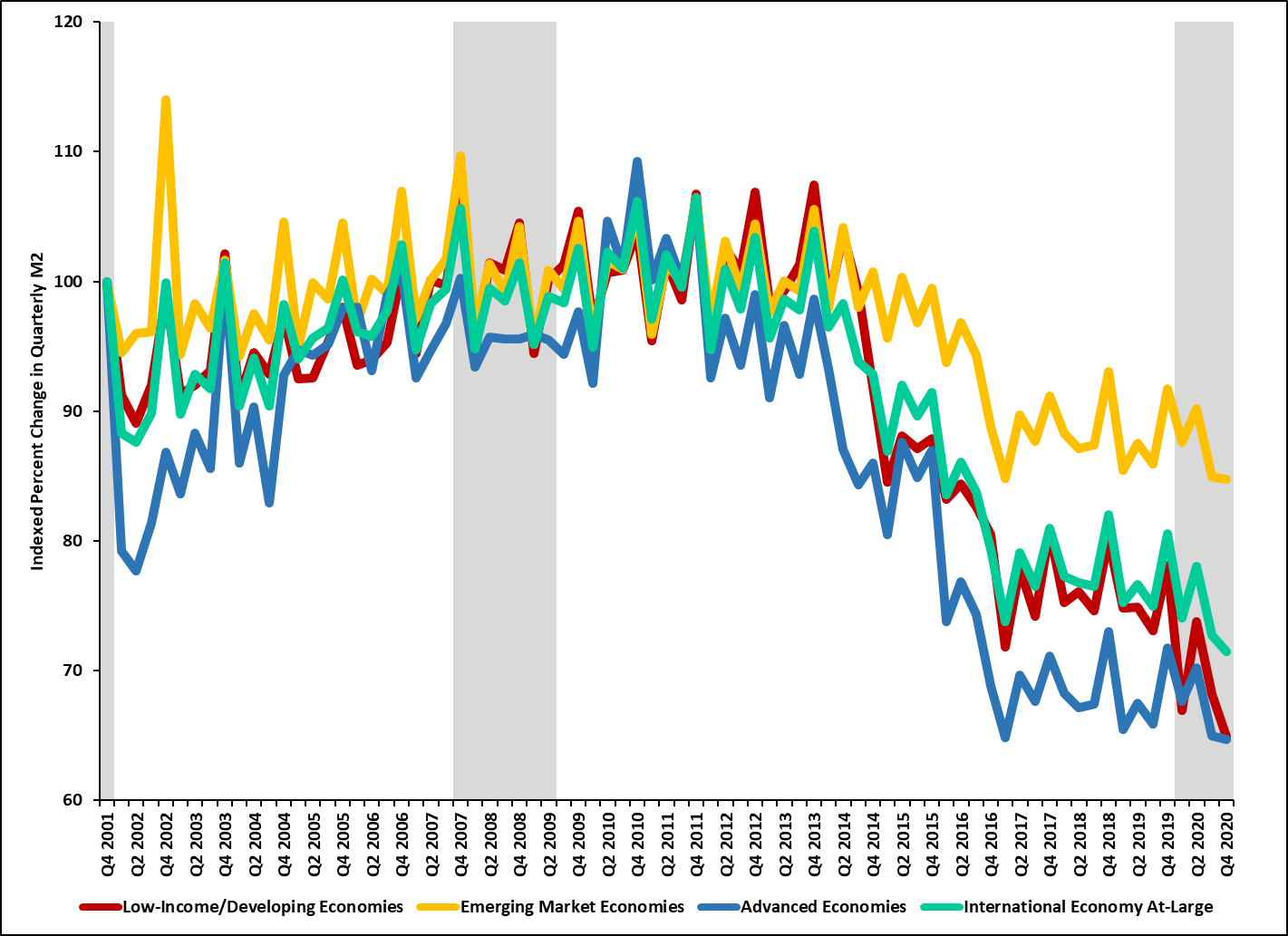

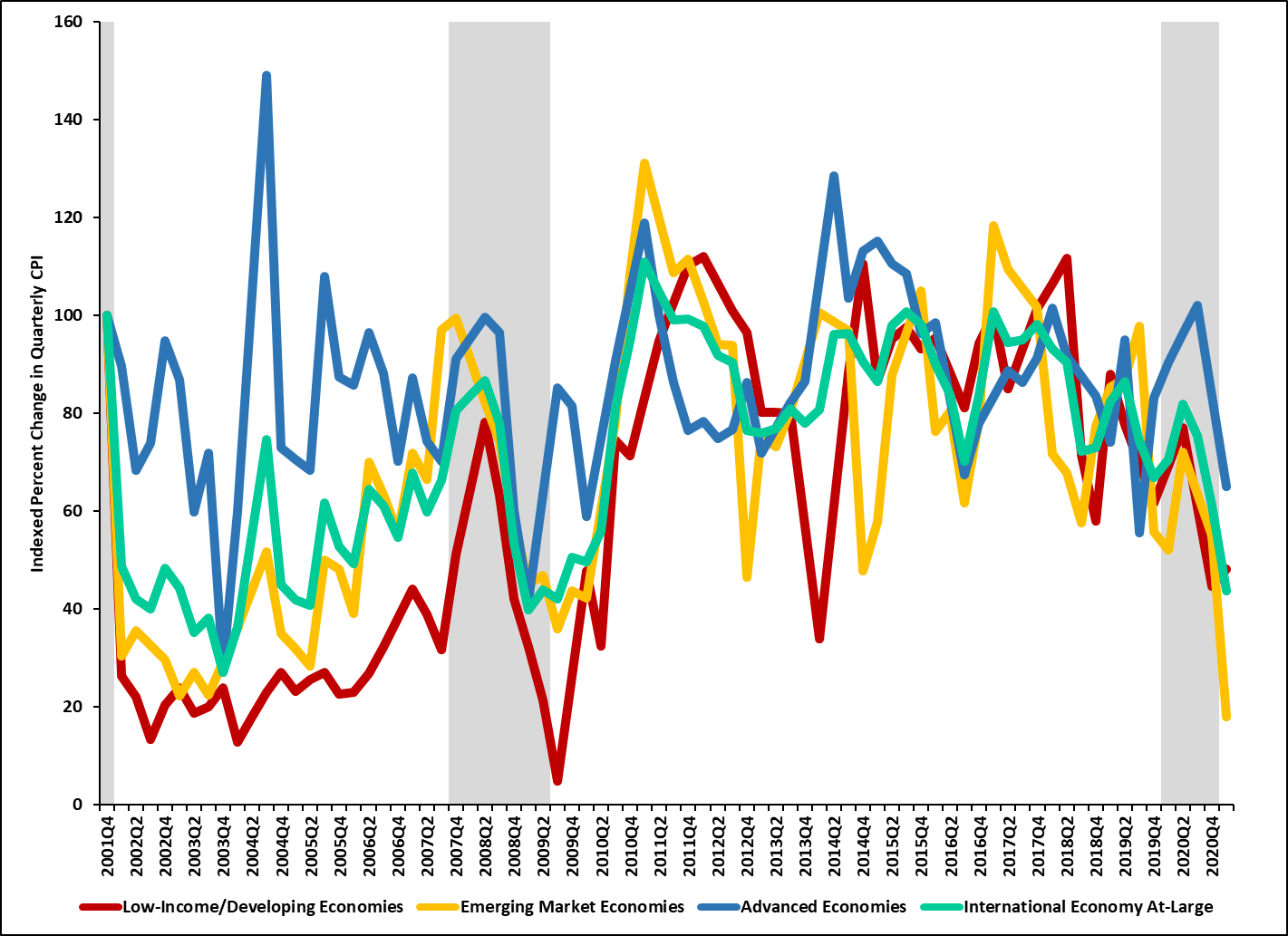

A rudimentary examination of recent macroeconomic data suggests a fraying relationship between the money supply and inflation. Figures 1 and 2 below examine recent trends in money growth, as proxied by the M2 monetary aggregate, and inflation over the past 20 years, including three of the most recent global financial crises to date. As shown within Figure 1, M2 rose after the early 2000s recession, and stagnated following the 2008 Financial Crisis, however, these movements were not congruently reflected within Inflation. As shown within Figure 2, global inflation declined after the early 2000s recession, with brief spikes among advanced economies, and proceeded to decline precipitously in the latter stages of the economic expansion following the 2008 Financial Crisis. At face-value, these trends over the last two economic cycles engender good reason for caution when expecting stimulus measures to spark an equivalent rise in global inflation. They are further indicative of lower spending patterns which have reduced the efficacy of stimulus measures in producing a broad-based acceleration in economic activity[12].

The casual mechanisms driving the slowdown in M2 growth are complex, encompassing a tightening regulatory environment for the financial services sector and protracted periods of accommodative monetary policy through lower interest rates[13]. The influence of such factors is particularly acute during the early stages of a new economic cycle, where central banks maintain a lower interest rate posture to encourage increased market activity, limiting the opportunity cost of saving, while private financial institutions exercise increased caution when providing credit services, accounting for a rebounding, yet volatile, recovery[14]. Yet, systemic factors are also at play, including a progressive deceleration in global GDP growth due to a fundamental shift in demand for goods versus services, as well as technological advances that have transformed the process of market-based intermediation, and left traditional financial institutions with much less influence over the expansion or contraction of the money supply[15]. Altogether, these factors have diminished the efficacy of conventional institutions and policies to channel stimulus measures into increased economic activity via spending, resulting in depressed global inflation.

Figure 1: Index of Global Quarterly M2 Growth (source: IMF, NBER, Author’s Calculations)

Figure 2: Index of Global Quarterly Consumer Price Index Growth (source: IMF, NBER, Author’s Calculations)

Divorcing Government Debt from Inflation

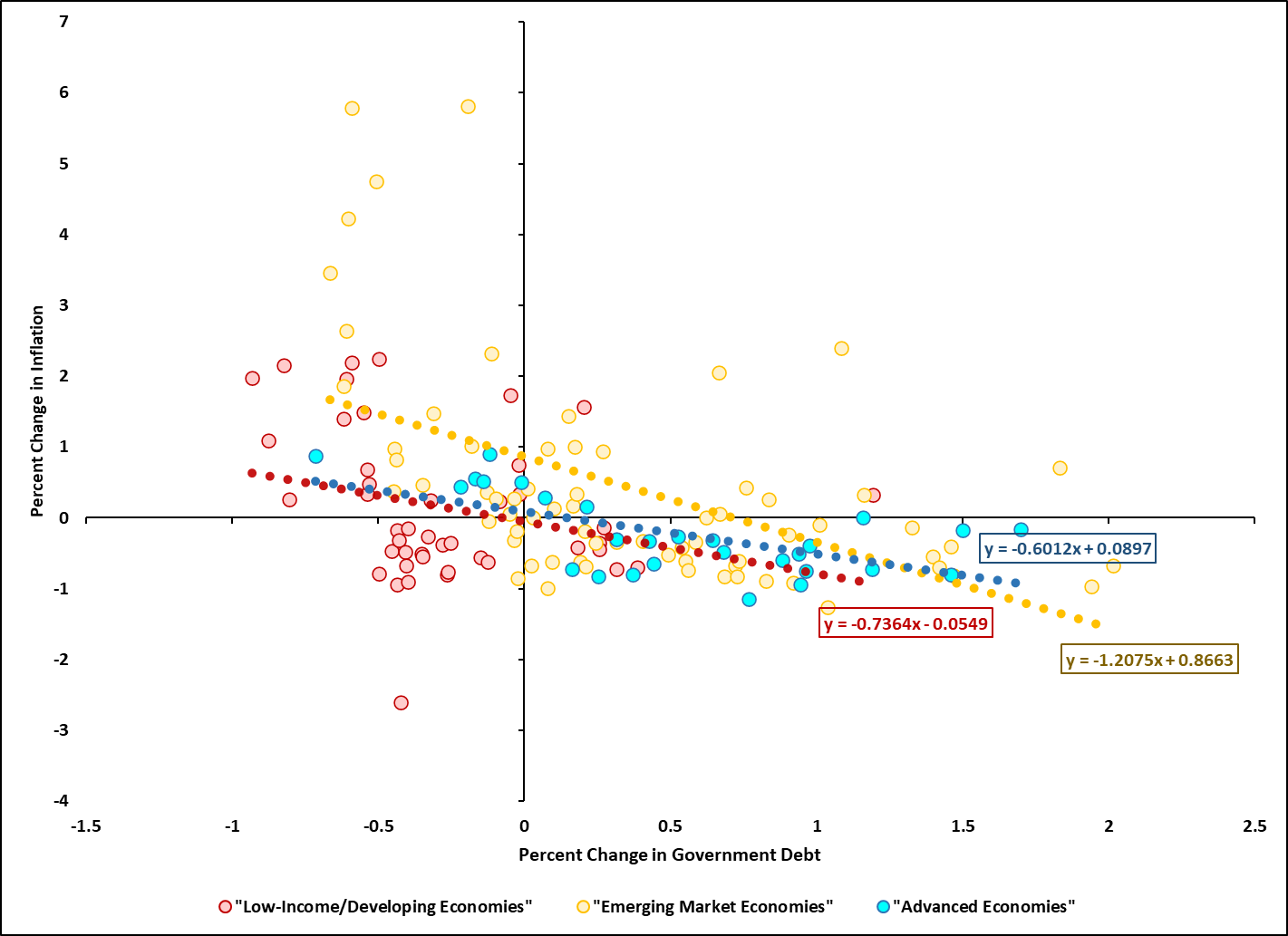

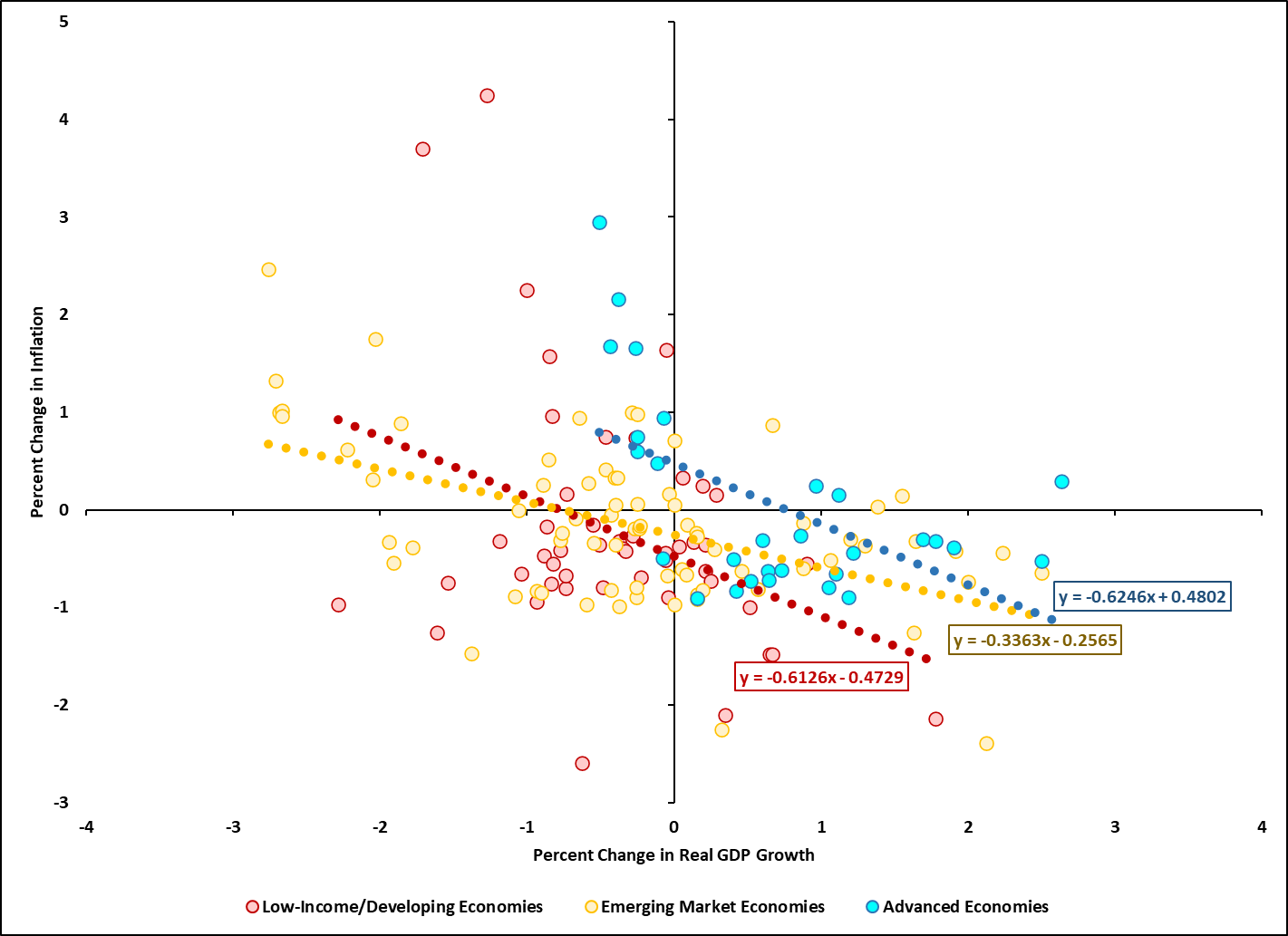

Recent macroeconomic data additionally portends an accelerating disassociation between government debt and inflation. As mentioned previously, classical macroeconomic theory posits that an increase in government debt generates repayment concerns leading to downward pressure on the currency of a borrowing country and rising inflation expectations[16]. These theoretical dynamics are refuted in Figure 3, positing an inverse relationship between the percent change in government debt between 2001 and 2021, and the percent change in inflation between 2001 and 2021, among economies across the wealth spectrum. In other words, increased government debt balances depress long-term inflation. Figure 4 contextualizes these results through ascertaining a similar inverse relationship between the 20-year percent change in government debt, and 20-year percent change in real GDP growth. Generally, inflation is positively associated with economic growth, since prices are driven by the velocity of demand therefore, these results suggest rising levels of government debt depress economic growth and, in turn, inflation.

Such contractionary effects generally result from fiscal retrenchment among households and businesses, whose sentiments and spending decisions are uniquely sensitive to fluctuations in fiscal policy, influenced in part, by government debt management. For example, Japan enacted several consumption taxes to offset high levels of government debt accumulated in response to a prolonged period of stagflation originating in the early 1990s which have continued to depress its economic growth[17]. Similarly, increased levels of government debt in the United States accrued during the 2008 Financial Crisis led to a series of politicized austerity measures through fiscal cliffs and government shutdowns which disrupted consumer and business spending during the early stages of its recovery[18]. Many countries in Europe adopted a similar approach to managing government debt during the European Sovereign Debt Crisis specifically, in response to fulfilling their obligations outlined within crisis-induced reforms to the Stability and Growth Pact which increased deflation risks and threatened a prolonged economic slowdown[19]. Remarkably, in each of these cases, lower economic growth has led to stagnation or deflation, rather than inflation.

Figure 3: Change in Government Debt vs. Inflation (source: IMF, Author’s Calculations)

Figure : Change in Real GDP Growth vs. Inflation (source: IMF, Author’s Calculations)

The New Class of Global Inflation Drivers

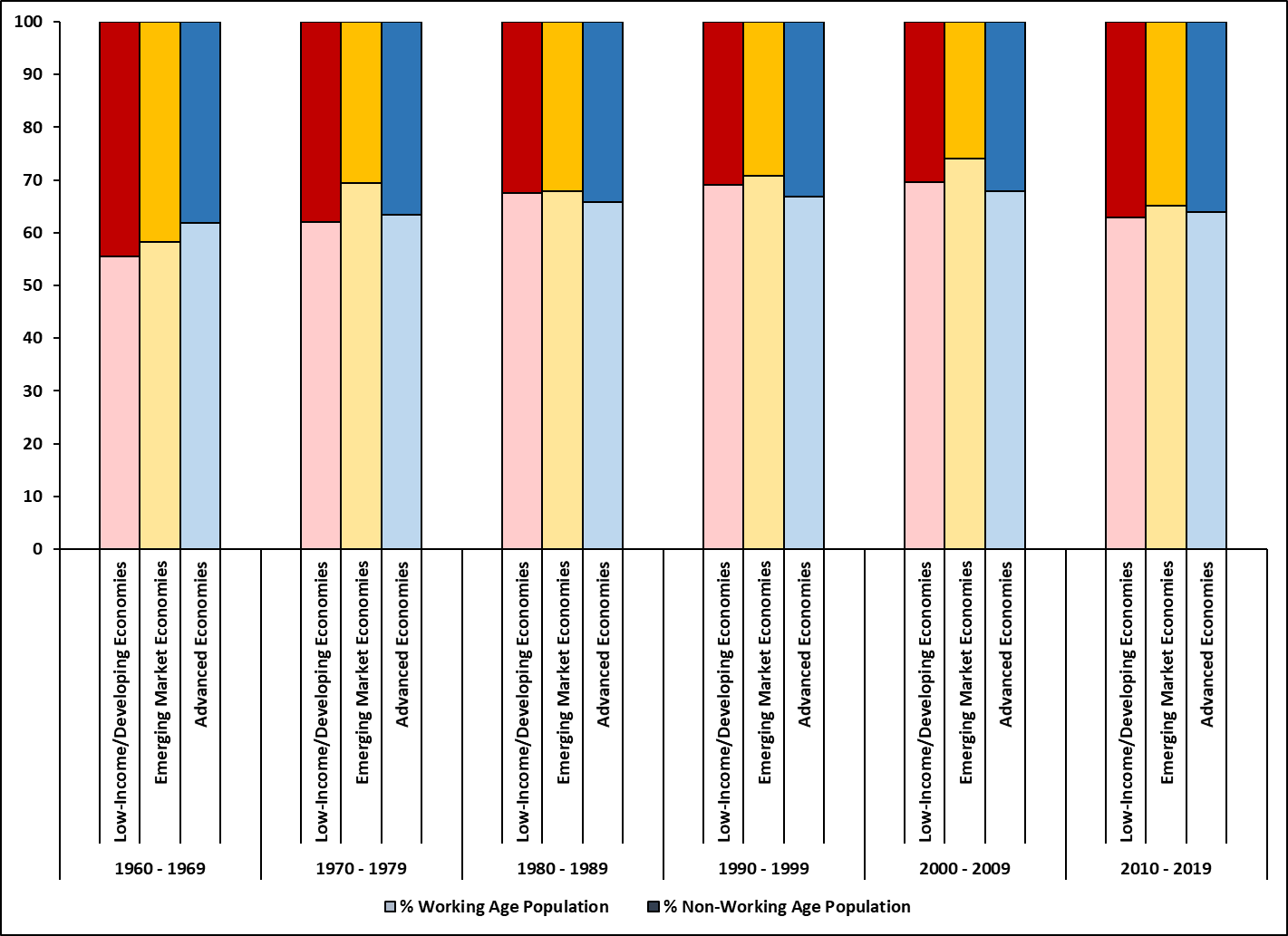

The remainder of this analysis will examine alternative forces which have begun to exert an increased influence over the trajectory of global inflation, including aging demographics, productivity gains, as well as inflation expectations. As per Figure 5 below, economies across the wealth spectrum are coping with a demographics transition driven by plateaus in their working-age population due to higher life expectancies and declining fertility rates[20]. This phenomenon, which emerged at the turn of the century and accelerated during the past decade, enabled most economies to experience declines in their working age population, creating asymmetry between the number of individuals exiting the workforce compared to new entrants. Such asymmetry has been shown to create deflationary pressures through depressed wages, business formations, as well as economic growth[21]. While demographic transitions are natural, cyclical phenomena, the irregularities produced by this current cycle could have a pronounced impact on the composition of labor markets and the economic growth they are able to engender.

Figure : Changes in Working Age Population by Decade (source: IMF, Author’s Calculations)

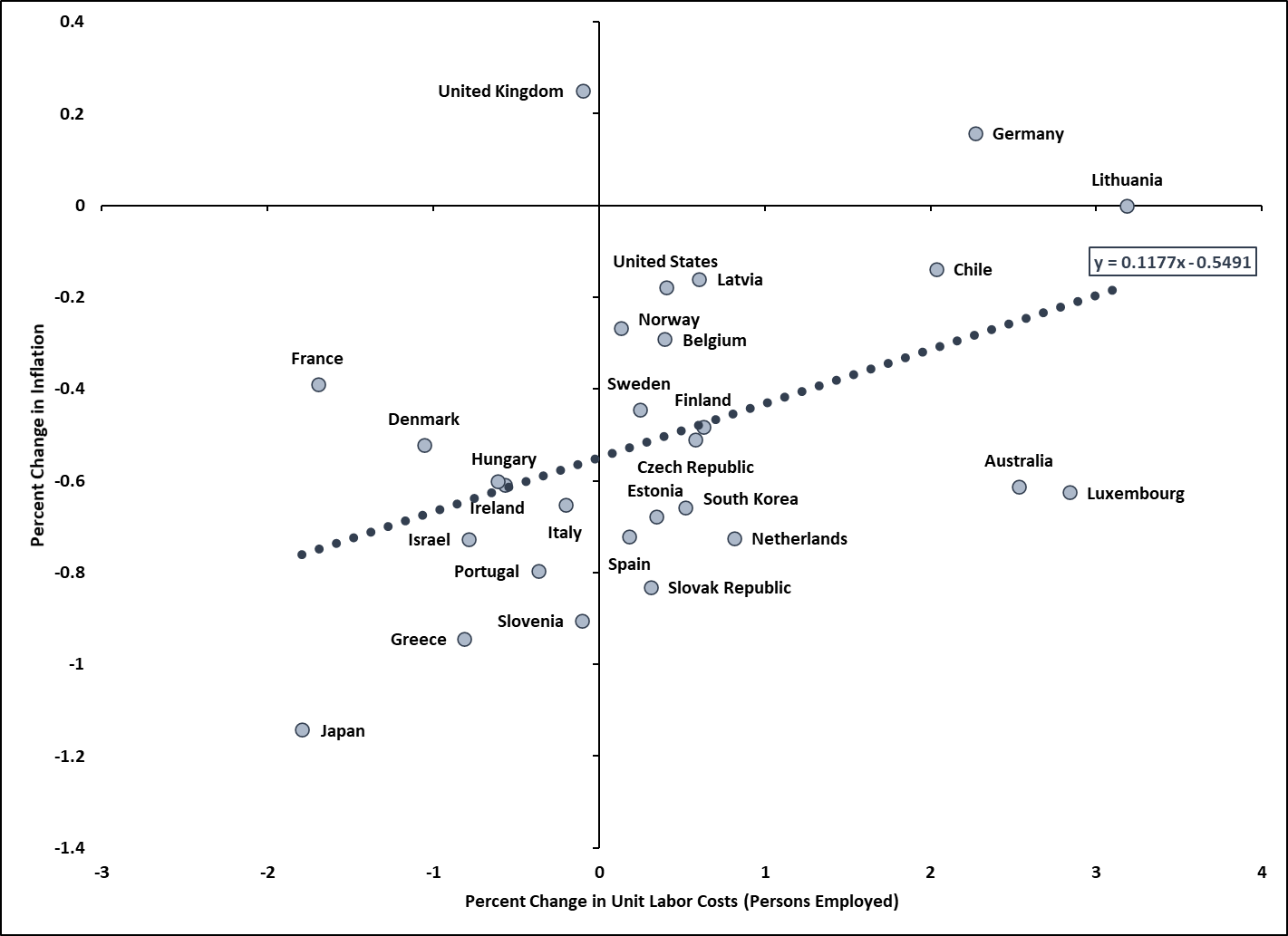

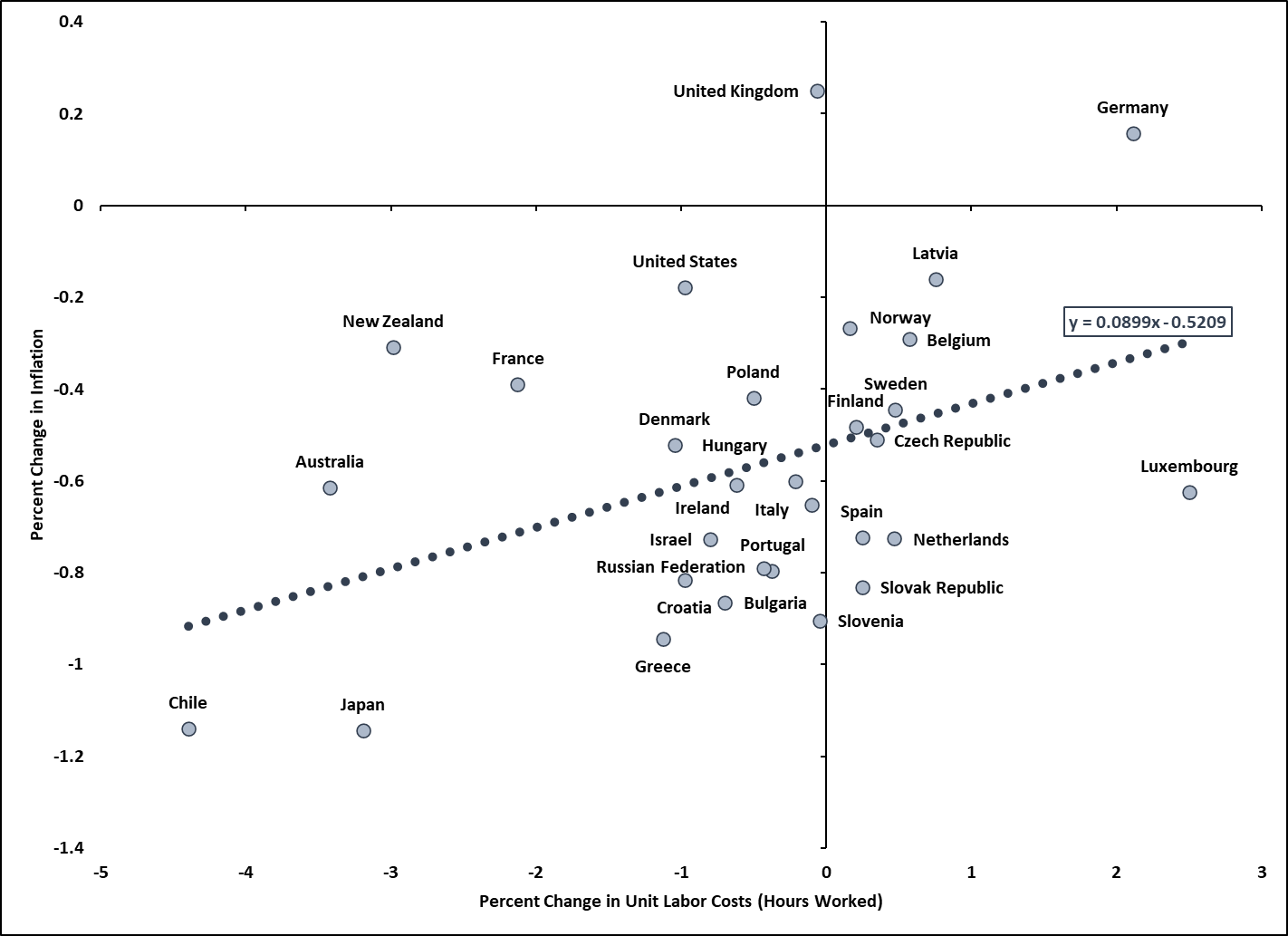

Productivity growth, specifically rising unit labor costs, have proven to be another potent driver of global inflation. Classical economic theory suggests, ceteris paribus, that increases in inflation roughly mirror wage growth less productivity growth[22]. Therefore, unit labor costs, the price of labor paid per unit of output, is often seen as a leading indicator of core consumer price indexes since higher wages increase consumption capacity, bolstering economic growth[23]. This relationship is depicted in Figures 6 and 7 below, demonstrating a positive association between a 20-year percent change in unit labor costs, calculated in terms of persons employed and hours worked, and a 20-year percent change in inflation among many advanced and emerging market economies. The existence of a relationship between unit labor costs and inflation, in conjunction with recent structural headwinds including a productivity slowdown driven by capital deepening as well as labor shortages forcing firms to improve production efficiency[24], not only explain the slowdown in global inflation which occurred prior to 2021, but additionally offer some relief that its present acceleration might be restrained by the persistence of these issues.

Figure : Change in Unit Labor Costs (Persons Employed) vs. Inflation (source: OECD, IMF, Author’s Calculations)

Figure : Change in Unit Labor Costs (Hours Worked) vs. Inflation (source: OECD, IMF, Author’s Calculations)

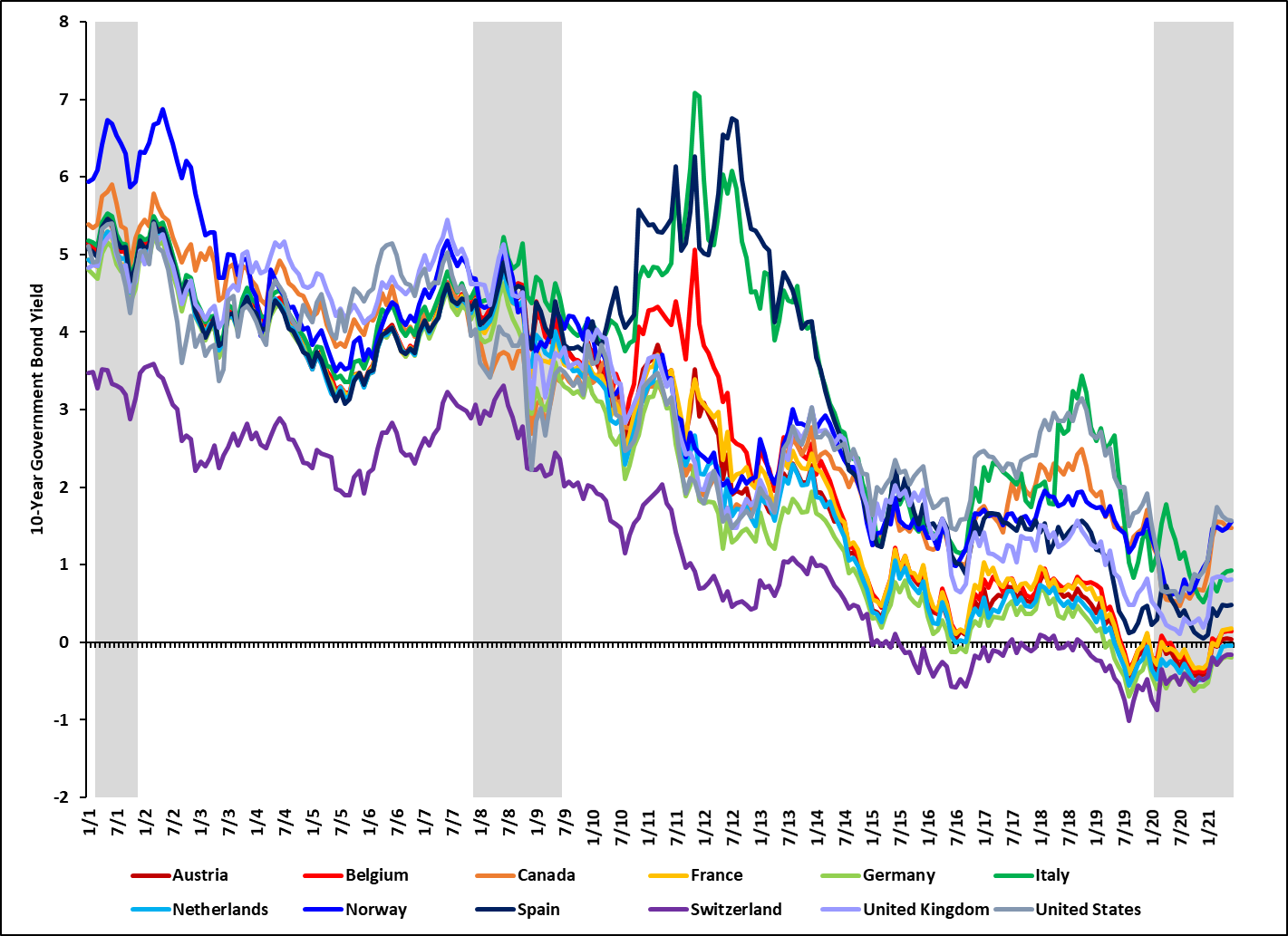

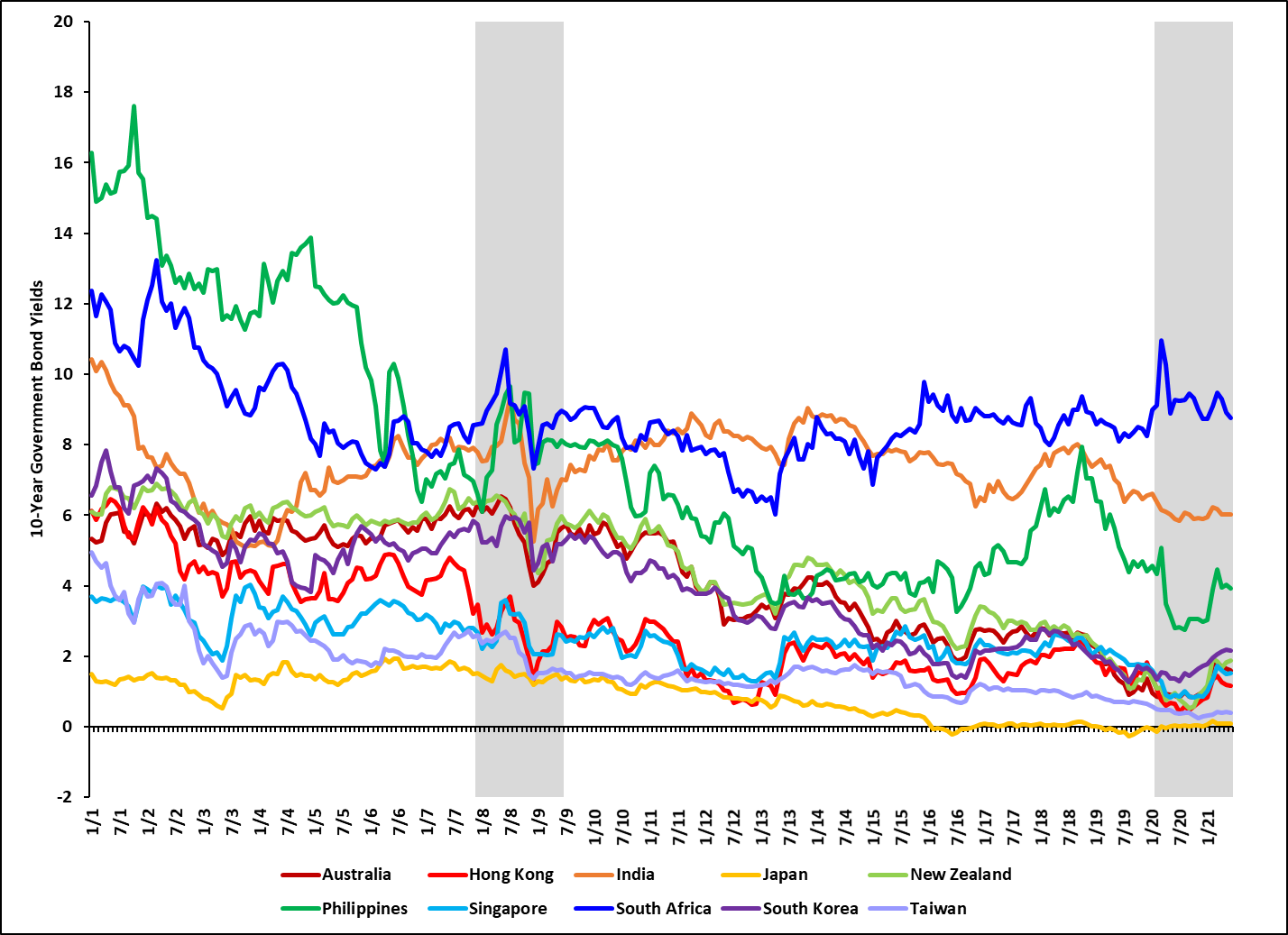

Finally, the improved anchoring of inflation expectations has exerted increased influence over global inflation outcomes. In other words, long-term inflation expectations held by both households and businesses has rendered them relatively insensitive to price shocks, limiting their propensity to demand wage increases or raise wages which generate higher inflation[25]. Empirical studies have suggested the anchoring of inflation expectations substantially improved following the 2008 Financial Crisis[26], and that sector-specific Phillips Curves have flattened in recent years which has elevated the importance of inflation expectations when determining its implications for sector-specific inflation risks[27]. Figures 8 and 9 below demonstrate these trends by tracking the fluctuation of 10-year government bond yields, which are positively associated with inflation expectations, over the past 20 years. With the exception of South Africa, India, and several other emerging market economies, 10-year government bond yields in most countries have declined significantly, suggesting that improved anchoring of inflation expectations, in addition to lower interest rates, have been important drivers of recently tepid global inflation growth.

Figure : 10-Year Government Bond Yields – Americas & Europe (source: TradingEconomics, NBER, Author’s Calculations)

Figure : 10-Year Government Bond Yields – Africa, Asia & Oceania (source: TradingEconomics, NBER, Author’s Calculations)

Conclusion

The recent rise in global inflation in response to a timely rescission of macroeconomic headwinds induced by the coronavirus recession merits further attention, but presently remains far from concerns of being uncontrollable. While historic levels of economic stimuli are creating an upward momentum in prices, the impact of an enlarged money supply and government debt levels has increasingly weakened over the past several decades. Conversely, persistent structural forces such as aging demographics, productivity gains, and well-anchored inflation expectations maintain a considerable influence over global inflation patterns and are likely to restrain runaway growth if such were to occur. Considering the likely transience of this current spike in global inflation, the real challenge for policymakers will be determining an appropriate combination of policy tools to maintain a healthy momentum in price growth complimenting countries’ return to a new normal. If managed properly, the current trajectory of global inflation could help, rather than hinder, the international economy in starting a new economic cycle on the right foot.

- Meyer, Victoria, and Jake Caporal. Rep. The Shifting Roles of Monetary and Fiscal Policy in Light of Covid-19. Center for Strategic & International Studies, February 2021. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/210223_Meyer_Monetary_Fiscal.pdf?lPd.UOY.lxNalGcHcCG4A7irYwWBONFr. ↑

- Riley, Charles. “Global Inflation Hasn’t Been This High Since 2008.” CNN Business. June 3, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/06/02/economy/inflation-oecd/index.html. ↑

- Bernanke, Benjamin S. “Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble.” News & Events. Speech presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, January 10, 2010. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20100103a.htm. ↑

- Jordà, Òscar, Chitra Marti, Fernanda Nechio, and Eric Tallman. Rep. Why Is Inflation Low Globally? Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, July 15, 2019. https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2019/july/why-is-inflation-low-globally/. ↑

- Orphanides, Athanasios. “European Crisis and its Implications for Global Inflation Dynamics.” Globalisation and Inflation Dynamics in Asia and the Pacific 70 (2013): 131-135. ↑

- Arias, Maria A., and Yi Wen. The Liquidity Trap: An Alternative Explanation for Today’s Low Inflation. No. 2. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2014. ↑

- Sheets, Nathan, and George Jiranek. Tech. Is Higher Global Inflation Around the Corner? PGIM Fixed Income, September 2020. https://www.pgim.com/fixed-income/white-paper/higher-global-inflation-around-corner. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Chamon, Marcos, and Jonathan D. Ostry. “A Future with High Public Debt: Low-for-Long Is Not Low Forever.” IMFBlog (blog). International Monetary Fund, April 20, 2021. https://blogs.imf.org/2021/04/20/a-future-with-high-public-debt-low-for-long-is-not-low-forever/. ↑

- “Central Banks to Pour Money Into Economy Despite Sharp Rebound.” Bloomberg News. April 19, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-04-19/robust-rebound-won-t-augur-end-to-stimulus-central-bank-guide. ↑

- Del Negro, Marco, Domenico Giannone, Marc Giannoni, and Andrea Tambalotti. “Global Trends in Interest Rates.” VOXEU.org (blog). Centre for Economic Policy Research, November 12, 2018. https://voxeu.org/article/global-trends-interest-rates. ↑

- Wu, Kelsey, and Max Thomasberger. “When Will the Global Consumer Class Recover?” Future Development Blog (blog). The Brookings Institution, November 25, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/11/25/when-will-the-global-consumer-class-recover/. ↑

- Pelagidis, Theodore, and Evangelia Desli. “Deficits, Growth, and the Current Slowdown: What Role for Fiscal Policy?.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 26, no. 3 (2004): 461-469. ↑

- Sheets, Nathan, and George Jiranek. Tech. Is Higher Global Inflation Around the Corner? PGIM Fixed Income, September 2020. https://www.pgim.com/fixed-income/white-paper/higher-global-inflation-around-corner. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Noble, Gregory W. “Too Little, Too Late? Raising the Consumption Tax to Shore Up Japanese Finances.” The Japanese Political Economy 40, no. 2 (2014): 48-75. ↑

- McGahey, Richard. “The Political Economy of Austerity in the United States.” Social Research 80, no. 3 (2013): 717-748. ↑

- Monastiriotis, Vassilis, Niamh Hardiman, Aidan Regan, Chiara Goretti, Lucio Landi, J. Ignacio Conde-Ruiz, Carmen Marín, and Ricardo Cabral. “Austerity Measures in Crisis Countries—Results and Impact on Mid-Term Development.” Intereconomics 48, no. 1 (2013): 4-32. ↑

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Long-Run Macroeconomic Effects of the Aging US Population. “Aging and the Macroeconomy: Long-Term Implications of an Older Population.” (2012). ↑

- Glassman, Jim. “What an Aging Population Means for the Economy.” Markets and Economy (blog). JP Morgan Chase & Co., March 4, 2020. https://www.jpmorgan.com/commercial-banking/insights/what-aging-population-means-for-economy. ↑

- Tsang, Eric. Rep. What Explains the Low Inflation in the US? A Review of Recent Literature. Hong Kong Monetary Authority, August 29, 2019. https://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/publication-and-research/research/research-memorandums/2019/RM10-2019.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Brauer, David A. “Do Rising Labor Costs Trigger Higher Inflation?.” In Handbook of Monetary Policy, pp. 701-708. Routledge, 2020. ↑

- Rich, Rob. “What Are Inflation Expectations, and Why Do They Matter?” Cleveland Fed Digest. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, May 28, 2019. https://www.clevelandfed.org/en/newsroom-and-events/cleveland-fed-digest/ask-the-expert/ate-20190528-rich.aspx. ↑

- Grishchenko, Olesya, Sarah Mouabbi, and Jean‐Paul Renne. “Measuring Inflation Anchoring and Uncertainty: A US and Euro Area Comparison.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 51, no. 5 (2019): 1053-1096. ↑

- Luengo-Prado, María José, Nikhil Rao, and Viacheslav Sheremirov. “Sectoral Inflation and the Phillips Curve: What has Changed Since the Great Recession?.” Economics Letters 172 (2018): 63-68. ↑