Graphic by Maralmaa Munkh-Achit

Written by: Ashley Hock and Jordan Perras

Edited by: Sonali Uppal

Since World War II, Americans have used homeownership as a popular means to build wealth through home equity and rising property values. Yet, Black Americans have been historically excluded from this popular wealth accumulation tool. A recent report from researchers at Gallup and the Brookings Institution notes that a home in a majority Black neighborhood is likely to be valued for twenty-three percent less than a near-identical home in a majority-white neighborhood. To understand how this disparity arose and why it has persisted, we must review the federal housing policy that emerged in the early 1900s.

During the Great Depression, the federal government implemented several policies to address a nationwide housing shortage and make homeownership more accessible through lower interest rates and longer amortization periods. However, the implementation of these new policies had specific requirements that codified racial discrimination and segregation. In the decades following the New Deal, the federal government enabled residential segregation through redlining. The practice was only in place through the 1960s, though Black Americans are still grappling with its effects today.

The Origins

In 1934, the U.S government established the Federal Housing Association (FHA) to address the nation’s housing shortage. The new agency subsidized the mass production of public housing developments. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein points out how public housing units were inhabited mainly by white families who could not find housing anywhere else. Many people think of public housing as a shelter for people who cannot afford it. Rothstein refutes this point saying, “public housing’s original purpose was to give shelter not to those too poor to afford it but to those who could afford decent housing but couldn’t find it because none was available” (Rothstein 18). The public housing program created by the New Deal laid out a specific set of requirements. The new program required “separate projects for African Americans, segregated buildings by race, or [exclusion of] African Americans entirely from developments” (Rothstein 19).

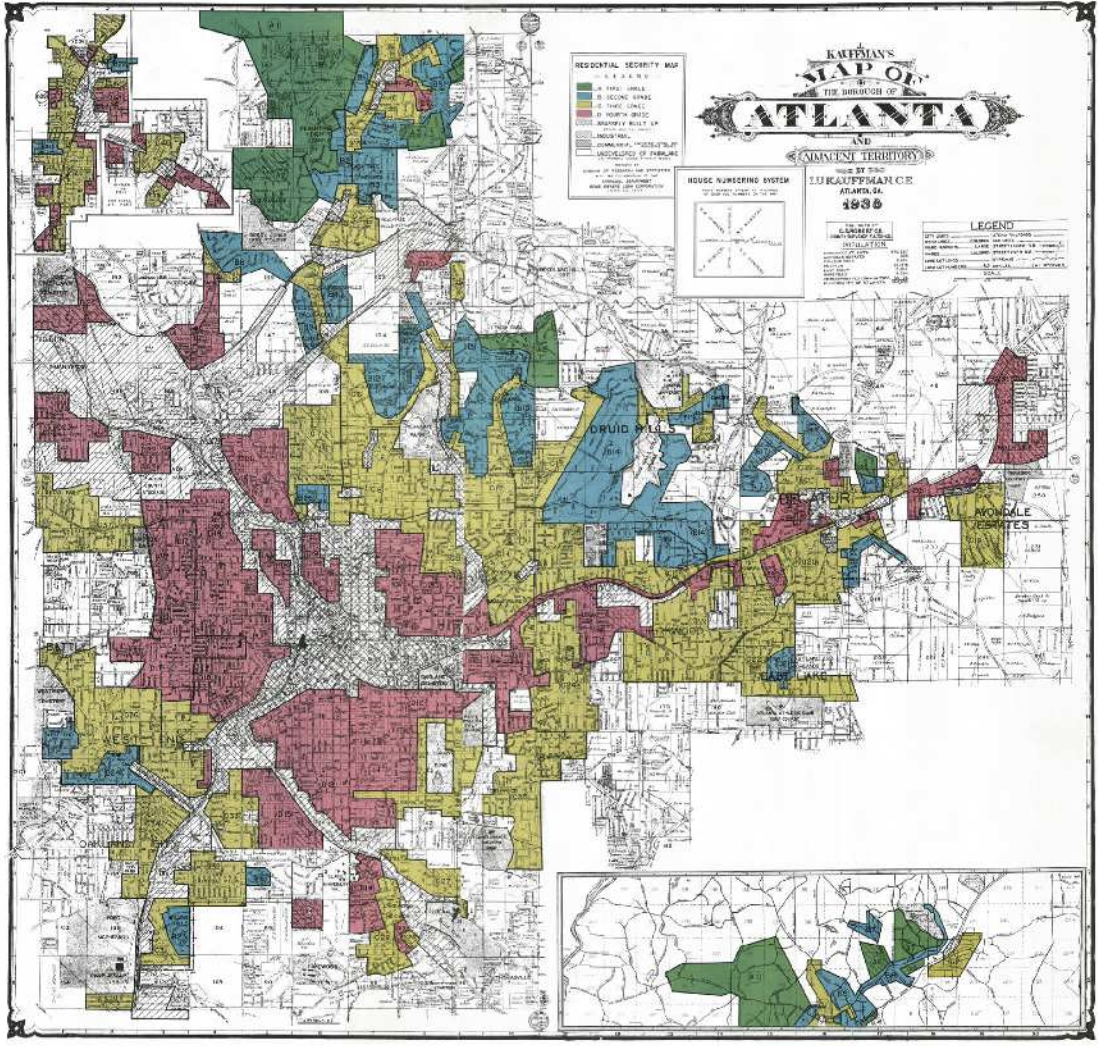

The creation of the FHA in 1934 led to changes in the mortgage lending system to encourage people to buy homes. Standard practices such as thirty-year fixed-rate mortgages have their origins in this era of legislation. However, to help insure mortgages, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created color-coded maps to assess the relative ‘riskiness’ of backing mortgages in different neighborhoods. Neighborhoods shaded green and blue were considered the most stable and low risk, with green neighborhoods seen as the safest. However, yellow and red neighborhoods were considered in decline or hazardous, respectively. The FHA considered mortgages in red neighborhoods “too risky” to back3. Hence the term ‘redlining.’

Figure 1: Residential Security Map of Atlanta5

On the surface, the use of these ‘residential security maps,’ as the FHA called them, would not seem like a tool for residential segregation. However, one of the primary criteria used in the assessment was the racial composition of a neighborhood. Neighborhoods shaded green were populated by White people only. Blue neighborhoods were seen as areas that were not at risk of attracting Black people. Yellow neighborhoods were seen as places declining in desirability (and thus, value) because Black people had started to move there. Finally, red neighborhoods were populated primarily by Black people.3 The FHA did not back mortgages in yellow or red neighborhoods.

The primary justification for the FHA’s refusal to insure loans in yellow and red neighborhoods was that a Black person buying a home in a particular neighborhood would decrease the property value of all of the homes in that area, a phenomenon termed ‘blight.’1 During the 1940s, developers were mass-producing suburbs to keep up with demand. Real estate brokers and banks played on the fear of decreasing property value to encourage white families to move to the suburbs. Black families, on the other hand, were not allowed to buy homes in the suburbs.1 This created a domino effect of ‘white flight’ from inner cities. As a result, residential segregation continued to increase.

State of Formerly Redlined Neighborhoods

Formerly redlined neighborhoods continue to suffer from a lack of investment. Because the HOLC identified these neighborhoods as ‘risky,’ little interest arose to invest in these communities. Redfin found that there are fewer restaurants and stores in the formerly redlined neighborhood, and economic development in these areas is stagnant4. A 2018 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) found that low-to-moderate-income families currently inhabit roughly 74 percent of formerly redlined neighborhoods. In contrast, 91 percent of neighborhoods shaded green are middle-to-upper income areas today. Furthermore, 64 percent of them are primarily minority neighborhoods.5 The NCRC study also found that formerly redlined neighborhoods have seen the least demographic change since the practice was made illegal. Walking down two adjacent blocks or neighborhoods in many U.S. cities can highlight the impact of decades of racist policies.

Black Homeownership Today

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 formally outlawed redlining, but statistics related to Black homeownership and formerly redlined neighborhoods make it clear that the damage has already been done. A report by Redfin Real Estate Brokerage found that a homeowner in a formerly redlined neighborhood gained roughly fifty-two percent less in personal wealth from property values than one in a formerly greenlined neighborhood.4 The Redfin report also found that home prices in formerly redlined neighborhoods are significantly lower today than those in neighborhoods that were shaded green or blue.4 Estimates from the Brookings report note that historic devaluation costs Black homeowners $156 billion in cumulative losses today. Bias from home appraisers also influences these values and can cost individual homeowners over $100,000[7], even though home appraisers are in theory bound by the Fair Housing Act to conduct home appraisals free of discrimination. Unsurprisingly, given these hurdles, homeownership rates for Black households are lower than that of White households. Forty-four percent of Black families today own a home compared to seventy-three percent of White families.

Reparations

Although federal housing policy has not made a significant dent in addressing these existing disparities, local policies supporting Black homeownership – often framed as reparations – have seen limited success. In late 2019, Evanston, Illinois, introduced one of the first municipal reparations programs in the United States for Black residents who can prove they are the descendants of Black homeowners in the area from 1919-1969 [6][8]. This initiative passed in March 2021 [6]. As outlined above, formerly redlined and segregated neighborhoods have seen dramatically less home price appreciation than historically white neighborhoods, drastically reducing the equity gains available to Black homeowners. Reparations are one way to rectify this financial disparity. Evanston’s $10 million program funded by cannabis sales tax will first be distributed in grants of $25,000 for homeownership-related costs such as mortgages, down payments, or home improvements [6][8]. While programs of this type do not fully address the financial and societal impact of segregation and redlining, they can be important steps towards grappling with longstanding inequalities.

References

[1] Gross, Terry. “A ‘Forgotten History’ Of How The U.S. Government Segregated America.” NPR. NPR, May 3, 2017. https://www.npr.org/2017/05/03/526655831/a-forgotten-history-of-how-the-u-s-government-segregated-america.

[2] Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: a Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[3] Lockwood, Beatrix. n.d. “The US Government Used These Maps to Keep Neighborhoods Segregated.” Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.thoughtco.com/redlining-definition-4157858.

[4]Richardson, Brenda. 2020. “Redlining’s Legacy Of Inequality: Low Homeownership Rates, Less Equity For Black Households.” Forbes Magazine, June 11, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brendarichardson/2020/06/11/redlinings-legacy-of-inequality-low-homeownership-rates-less-equity-for-black-households/.

[5] Mitchell, Bruce, and Juan Franco. 2016. HOLC “REDLINING” MAPS: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality. NCRC.

[6] Perry, Andre M. & Ray, Rashawn, 1 April 2021. “Evanston’s grants to Black homeowners aren’t enough. But they are reparations.” Accessed April 2, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/evanston-housing-reparations/2021/04/01/4342833e-9243-11eb-9668-89be11273c09_story.html

[7] Kamin, Debra. “ Black Homeowners Face Discrimination in Appraisals.” New York Times, August 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/25/realestate/blacks-minorities-appraisals-discrimination.html

[8] Fies, Andy. “Evanston, Illinois, finds innovative solution to funding reparations: Marijuana sales taxes.” ABC News, July 19, 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/US/evanston-illinois-finds-innovative-solution-funding-reparations-marijuana/story?id=71826707