By: Jacob S. Warner

Once a constituent Republic of the Soviet Union, Belarus gained its independence in 1991 and has since then entered a unique dynamic with its Eastern neighbor, Russia. Over the last several decades, the slow expansion of Russian influence in Belarus has reached a critical phase in which Russia now poses a significant threat to Belarusian sovereignty. Such amplification of Russian power should be of great concern to countries within the Russian sphere of influence that value their sovereignty.

Since its inception as the Muscovite Tsardom in the 16th century, Russia has possessed a considerable ability to influence the nations in the surrounding region. Although Russia entered a deep recession by the close of 2014, this ability remains ironclad in Eastern Europe and Central

Asia. Even as the Russian GDP shrank by nearly three percent between 2014 and 2017, the centuries-long economic dependence those near it built up around Moscow has not changed [1]. This is most clearly the case with Belarus, whose economy relies on Russia for gas, oil, consumer products, and more. While this dependency of Belarus on the Russian economy allows the Kremlin, some influence in Belarusian internal policy, at the moment, there is a danger of Russia gaining additional influence in the country. For decades, Belarusian President Lukashenko has consolidated government power into his hands while at the same time also prevented Russia from absorbing his nation. One characteristic of his government, which somewhat supports economic independence from Russia, is its maintenance of state ownership of large tracts of the Belarusian economy. Should the Belarusian opposition parties take control from Lukashenko, their large-scale privatization policies may leave Russia an open-ended invitation to purchase a large part of the commanding heights of the Belarusian economy.

The Present State of Russian Influence

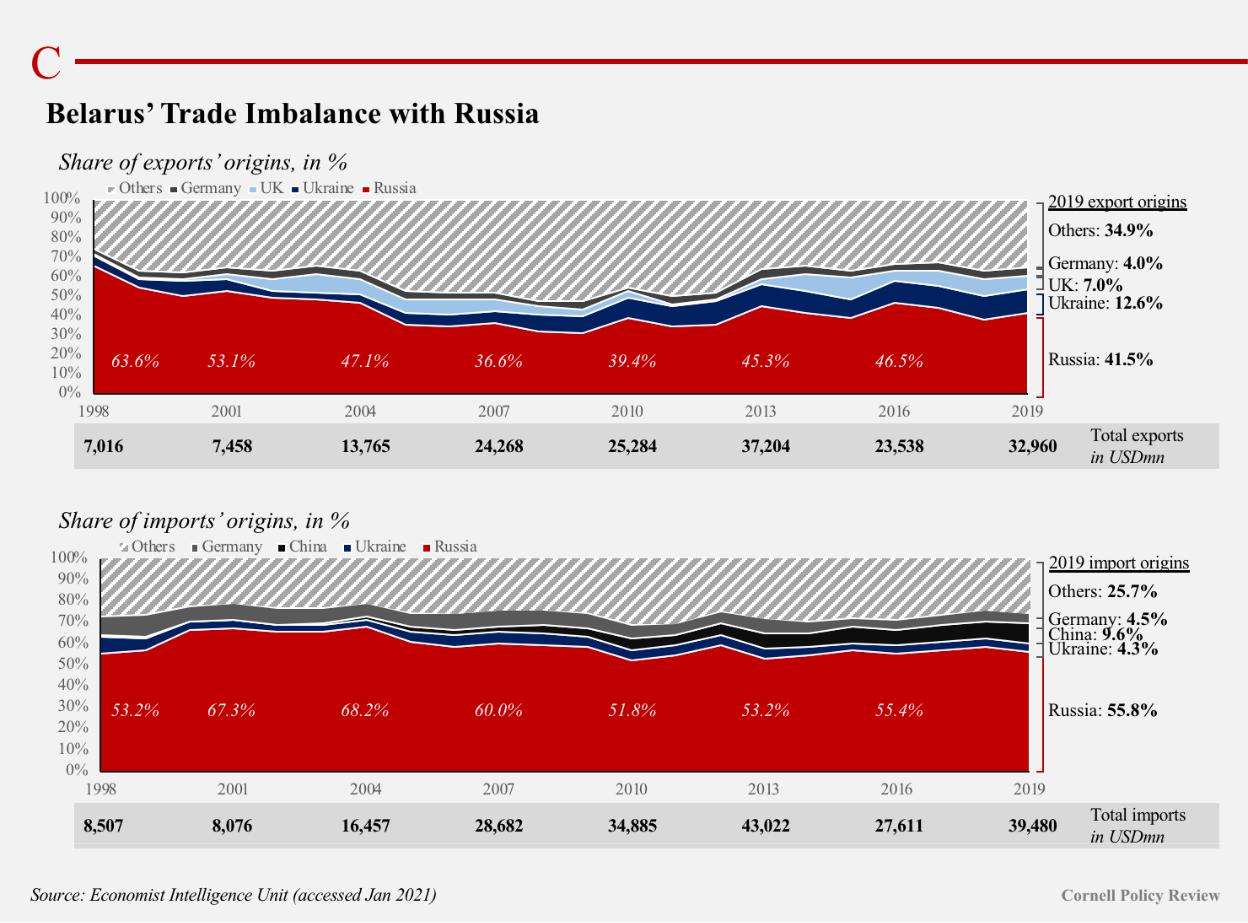

Throughout the 20th century, the republics of the Soviet Union specialized in certain industries so that they might function better as a whole. Under the watchful eye of Soviet economic planners, the Belarusian economy became ever more entwined with the Russian economy. This had the effect that each republic became increasingly dependent upon the other. Currently, Russia is, by a large margin, Belarus’ largest trading partner. Nearly 56% of Belarus’ exports go to Russia, and 41% of its imports are from Russia (Figure 1). This interdependency allows the Russian government to exert tremendous economic pressure on Belarus. Russia could coerce the Belarusian government to implement policies and take actions that directly benefit the Russian government. It could also use such pressure to ensure that Belarus does not escape these dependencies. The economic dependency of these former Soviet Republics, especially Belarus, has thus given Russia the ability to pressure Belarus and maintain its influence.

Figure 1:

While Belarus is relatively dependent on Russian imports, this dependence varies from industry to industry. Two important resources – Russian oil and natural gas – represent well-known reliance which are potentiated even further by Russia’s offering Belarus these resources below market price. A third area in which Belarus is dangerously dependent upon Russia is its armed forces. Not only are Russia’s armed forces much larger than their Belarusian counterpart, but those forces which Belarus does maintain are also entirely “comprised of Russian-origin equipment” [1]. These areas – oil, gas, and military equipment – are just a few of several strategic industries in which Belarus is dangerously dependent on Russian imports; they act as the thoroughfares through which Russia can extend economic pressure into Belarus. Together, they show that Russian power in Belarus is already immense.

Politics and the Economy

Compounding the situation of economic reliance, the current political climate in Belarus creates the significant danger that Russia may gain increased influence in Belarus within the next few years. Since the Fall of 2020, mass protests have raged in Belarus due to the seemingly corrupt nature of the recent Belarusian Presidential election. While President Lukashenko has many faults, since his rise to office, he has been a relatively steady opponent of Russian domination and a stable defender of Belarusian sovereignty. Lukashenko’s government has decided that the state should maintain control and ownership of the most important industries, known as the ‘commanding heights’ of an economy. According to the U.S. Department of State, at present, the Belarusian government maintains control of “at least 75%” of its GDP through its state-owned enterprises, or SOEs [8]. However, the maintenance of state control over such a vast area of the economy is disputed between Lukashenko’s controlling faction and major opposition factions.

Why the Opposition wants to Liberalize the Economy

In contrast to Lukashenko’s policy of maintaining the status quo, the opposition’s policies include implementing significant reforms to the Belarusian economy. A key step in their reformation of the economy includes the partial or complete privatization of large and medium-sized state-owned enterprises [3]. SOEs create several issues in Belarus that their large-scale privatization could solve; such issues include the considerable financial resources needed to maintain SOEs and the Belarusian economy’s reduced competitiveness. However, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) create two problems in Belarus: financial issues for the state and limited ability for economic growth.

Belarusian SOEs tie up billions of dollars from the state’s budget as they are mainly unprofitable. According to the International Monetary Fund, SOEs usually “significantly [underperform] private companies” [4]. This trend is true in most sectors of the economy, including construction, agriculture, and manufacturing. Data further shows that between 2013 and 2016, 20 percent of SOEs showed losses, and 33 percent faced liquidity problems [4]. In addition, SOEs’ “return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) were on average respectively around four and three times lower than those of private companies, and SOE average net profit was about twice lower” [4]. Such disparities would be even more pronounced if the data took into account government

subsidies. Since so many Belarusian SOEs lose money, the state must prop them up with subsidies so that they might continue to function. According to the World Bank, in Belarus in 2015, “the overall cost of state support to public enterprises amounted to 9.5% of GDP” [5]. These expenses thus tie up a large portion of the state’s budget that could be put to better use elsewhere.

The massive portion of the Belarusian economy that these state-owned enterprises make up hurts the economy in another way. In 2016, SOEs occupied over 60 percent of total output and 77 percent of output from the industrial sector [4]. The central role that the public sector occupies in Belarus’ economy and the low comparative profitability relative to the private sector affect the Belarusian economy. It affects the Belarusian economy such that it is, ceteris paribus, less profitable and thus less competitive.

Privatization can solve both two problems. Regarding SOE-induced budget tie-ups, once the companies are privatized, the state will no longer have to spend billions of dollars to prop up such unprofitable entities. Concerning the poor competitiveness of SOEs, without state ownership and support, newly privatized enterprises are forced into a competitive environment and must become profitable to remain viable. For these reasons, the Belarusian opposition by and large desires privatization of the state-owned commanding heights of their economy.

Foreign Direct Investment in Belarus

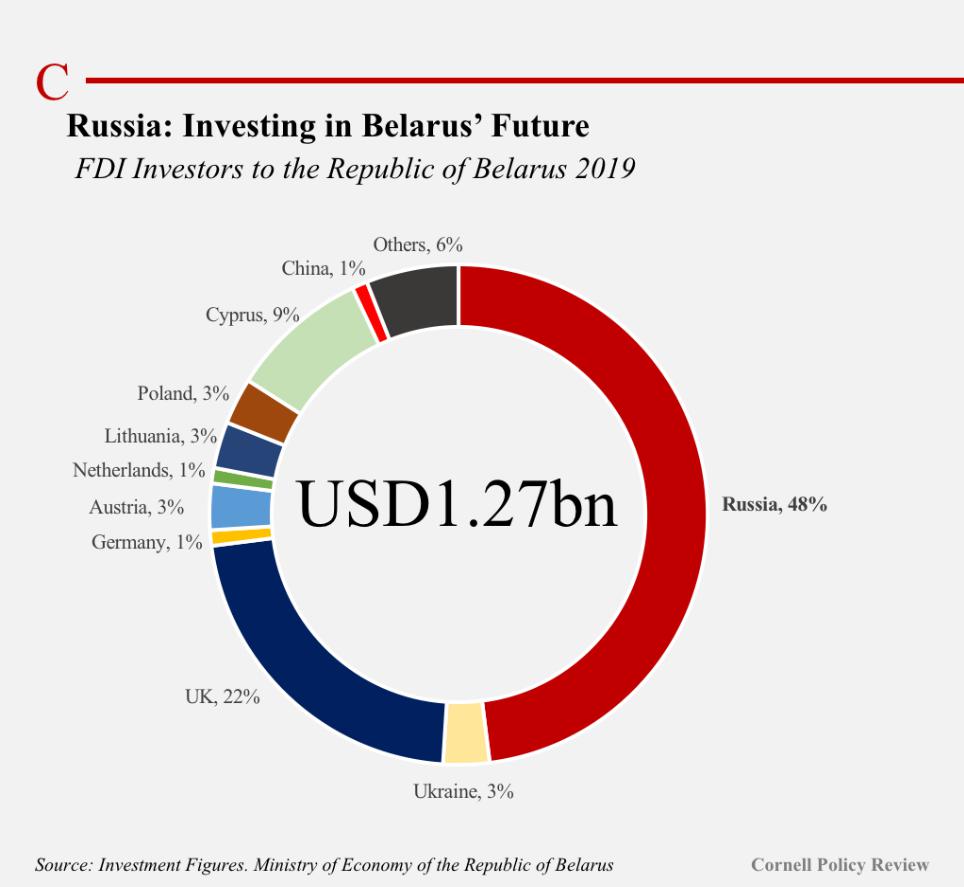

Unfortunately, such privatization may also create undesirable downsides for Belarus in that it may further Russia’s attempts to gain control of Belarus’ economic assets. Privatization will allow Russia to expand its power in Belarus because, in recent years, Russia has made up the majority of foreign direct investment flowing into Belarus. According to the National Bank of Belarus, about 1.27 billion dollars of foreign direct investment (FDI) flow into the country annually. Russian investments make up about 48% of such investment, nearly half of all foreign direct investment in Belarus (Figure 2). It is also worth noting that Cyprus, which has a large and wealthy Russian minority, makes up a disproportionately large share of FDI flowing into Belarus. Russians already have the will and means to invest heavily in the Belarusian economy at a rate nearly as much as every other country in the world combined [6]. While the Russians would not gain complete control of newly privatized industries, they would likely still purchase a

great deal of control over the commanding heights of the smaller, Russian-speaking, Belarusian economy. Should a new Belarusian government begin to privatize, Russia would thus attain increased influence over Belarus. Not only would it own some of the most important assets of the Belarusian economy, but Russia would also have direct control over those who work in such industries. According to the European Council on Foreign Relations, by “buying out large state-owned enterprises, for example, Russia could gradually turn the senior levels of these enterprises into its own political lobbyists” [7]. For these reasons, should the Belarusian opposition gain power and implement privatization policies, Russian influence is likely to grow.

Figure 2:

Potential Policy Solutions

The political and economic situations lead one to believe that the way to constrain Russian economic influence is to limit Russian investment. While there are several ways to go about this, the best method is to simply not privatize. At the very least, if the Belarusian government does not privatize its state-owned industries, Russians will not have the opportunity to buy parts of those industries. Some may argue that the government can still employ a privatization policy as long as it directly places limits on Russian investment. However, such a direct policy would not work for two reasons: political status and Russia’s reaction. Politically, Russia and Belarus are both parts of the Eurasian Economic Union and the Union State. In both unions, the two countries function in a single unified market, including the free movement of resources. Within such a framework, it is nearly impossible for Belarus to implement policies to directly discriminate against Russians with regard to direct investment. In addition, Russia’s possible reaction to such a policy poses an issue in its own right. As shown earlier, Russia, if it so chooses, can place tremendous economic pressure on Belarus. Should Belarus oppose Russian investment in such a direct manner, the Russian government may react aggressively. Thus, since it is unfeasible for Belarus to oppose Russian investment into its economy directly, an excellent way to prevent the growth of Russian influence is to simply not privatize its state-owned industries.

While such a method may stem the proliferation of Russian influence, it prolongs the detrimental effect of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) on the Belarusian economy. A two-pronged approach to reduce the harmful impact of the SOEs may be the optimal solution since this would support the growth of the private sector while reducing preferential treatment towards SOEs. According to the U.S. Department of State, in Belarus, “both the central and local governments’” policies often reflect an old-fashioned, Soviet-style distrust of private enterprise [8]. Distrust of this kind has brought about government suppression of the private sector in Belarus. Many laws are designed to “discriminate against the private sector” [8]. The result is that private firms face an unfair competitive situation. In market capitalist economies, private businesses compete to remain profitable. The implementation of policies to relax restrictions on privately owned businesses would allow this private sector to grow. Should the Belarusian government relax

restrictions on the private sector, such enterprises would grow far faster than their state counterparts due to their inherent competitive nature.

The second portion of this approach includes the elimination of preferential treatment towards SOEs. For the same reasons that relaxing restrictions on private businesses is beneficial, policies to reduce preferential treatment would help the private sector grow by providing a less biased environment. These policies can include regulation to set prices for monopolistic SOEs at competitive levels while “subjecting SOEs to the same laws and regulations regarding employment and labor costs as private competitors” [9]. As the private sector grows and the public sector receives less preferential treatment, the Belarusian economy would slowly transform to become more competitive while concurrently limiting Russian influence.

Russia poses a troubling threat to Belarus. Economic interdependence, high levels of Russian investment, and the potential liberalization of the Belarusian economy together place Belarus in a precarious situation. Nevertheless, policy solutions to help alleviate this situation are apparent. These solutions might include relaxing restrictions on the private sector, eliminating preferential treatment towards SOEs, and preventing liberalization policies. With proper policy solutions, hopefully, Belarus will possess the power it needs to maintain sovereignty from Russia.

References

- “Belarus.” CIA World Factbook. accessed December 2020. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/belarus/.

- “Annual Indicators.” Economist Intelligence Unit. accessed January 2021. http://country.eiu.com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/article.aspx?articleid=2010609784&Country=Be larus&topic=Economy&subtopic=Charts+and+tables&subsubtopic=Annual+indicators.

- Краткое Описание. “Новые Рабочие Места.” Беларусь Для Жизни. accessed January 2021.

- “Republic of Belarus Selected Issues.” International Monetary Fund (IMF). IMF Country Report No 17/384. published December 2017. accessed January 2021. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjC3rO QzsTuAhWkElkFHXxlBVEQFjABegQIBBAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.imf.org%2F~%2 Fmedia%2FFiles%2FPublications%2FCR%2F2017%2Fcr17384.ashx&usg=AOvVaw0zRPNY5 fX8Lf4DR9Isikgl.

5. Kremer, Alex. “Why Economic Reforms in Belarus are now more urgent than ever.” World Bank Blogs. accessed December 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/europeandcentralasia/why-economic-reforms-belarus-are-now-more-urgent-ever-0.

6.“Investment Figures.” Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus. accessed December 2020. https://www.economy.gov.by/en/FIGURES-en/.

7. Slunkin, Pavel. 2020, November 5. “Lukashenka Besieged: Russia’s Plans for Belarus.”

8. European Council on Foreign Relations. accessed January 2021. https://ecfr.eu/article/lukashenka-besieged-russias-plans-for-belarus/.

9. “2018 Investment Climate Statements: Belarus.” US Department of State. accessed January 2021. https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-investment-climate-statements/belarus/.

10. Ter-Minassian, Teresa. 2017, October. “Identifying and Mitigating Fiscal Risks from State-Owned Enterprises.” Fiscal Management Division, Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Identifying-and-Mitigating-Fiscal-Risks-from-State-Owned-Enterprises-(SOEs).pdf.