By Yiming Zhong

Edited by Courtney Schneider and Alessandra McCormack

Graphic by Sarah Lu

CEO and Founder Minhong Yu of New Oriental Education & Technology Group Inc., China’s largest private educational services provider, compiled an annual report and summary of his company’s activities in 2021. During that year, “New Oriental encountered an excessive number of barriers. Many businesses were uncertain for policy-related reasons, COVID-19, international relations, etc. Thanks to everyone’s efforts over the past six months, New Oriental has survived and maintained some strength. In response to the many obstacles encountered, several individuals banded together and assisted each other, working diligently to advance. The market value of New Oriental decreased by 90%, its operating income decreased by 80%, 60,000 employees were laid off, and cash expenditures such as tuition refunds, employee dismissal N+1, and office lease cancellations cost the company nearly 20 billion RMB.”1 These massive losses were largely a result of the Chinese Government’s Double Reduction Policy.2

On July 24, 2021, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council announced the, “Opinions on Further Reducing the Burden of Homework and Off-campus Training for Students in Compulsory Education,” or Double Reduction Policy. Its primary purposes were to reduce the homework burden on students in compulsory education, resolutely decrease off-campus tutoring in disciplines, and improve the standards of after-school services to meet the diverse needs of students.3

The Double Reduction Policy was initially issued in response to the call for a reduction in the excessive amount of homework and burdens of off-campus tutoring on students. It has since gained support from all Chinese provinces and city officials.

The private education sector in China used to be prosperous, with severe competition and enormous demand. However, the Beijing regime’s Double Reduction Policy on off-campus tutoring triggered massive bankruptcies among private education companies. Among those impacted was New Oriental, whose CEO – Minhong Yu – was left frustrated and teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. This frustration was not unique to Minhong Yu; discontent was widespread among private education organizations. This was merely a sliver of the severe scope of challenges posed by the Double Reduction Policy.

Many families shared this frustration as they could no longer seek off-campus tutoring and other means of increasing their childrens’ educational prospects. To address public confusion, the Chinese government revised their initial restrictions on the private education sector in order to improve relations and protect private entrepreneurs unrelated to the school curriculum.

On July 29, 2021, the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) issued a, “Notice on Further Clarifying the Scope of Off-campus Training Disciplines and Non-Disciplines in Compulsory Education.” Under this new policy, the definitions of “disciplines” and “non-disciplines” were more clearly defined. It stated that history, geography, mathematics, foreign languages (English, Japanese, Russian), physics, chemistry, and biology were disciplines–prevented from offering off-campus classes or tutoring services to students in compulsory education. Conversely, sports, art, music, and comprehensive practical activities (including information technology, labor, and technology education) were treated as non-discipline categories.4 By further defining disciplines and non-disciplines, the Ministry of Education of the PRC hoped to lessen academic burdens while promoting a more comprehensive education and creating a fairer and more equal education system.

The long-term goals of the Double Reduction Policy are to relieve students from an overwhelming amount of homework and off-campus schoolwork and facilitate on-campus clubs, activities, field trips, and other liberal arts-related education experiences. As students no longer felt the pressure to continue their education outside of regular school hours, they could spend their free time engaging in other activities.

However, unintentionally, the policy’s “double reduction” more adversely impacted the private sector’s off-campus tutoring–specifically the non-disciplinary education sector–by distorting the market demand, possibly contributing to more significant uncertainty in the yet-to-be-seen effects on Chinese youth in the long term.

The Social Context in China

China’s educational system is composed of individuals who accept the added pressures of its private, off-campus tutoring and frequent mock exam offerings. The Chinese public has embraced this long standing legacy. Often, enrolling in a good school is the only path to success for many young Chinese people and the only way to obtain a position in government or a well-known company with above-average pay. To outmaneuver the massive number of competitors in a 1.4 billion person population base, demand for off-campus education and tutoring has soared. This pressure has pushed young people to forgo entertainment and self-interest in the name of advancement, and has become the central theme of Chinese students’ childhoods.

After the Warring-Kingdoms era, the emperor Qin Shi Huang united all disparate kingdoms into a single empire. Under his leadership, China’s central bureaucracy was established. Qin Shi Huang and many later emperors attempted to find effective ways to hire or elect administrators to best serve China’s vast, densely populated empire.

In 605 A.D., under the Sui dynasty, leaders established a royal written examination that selected candidates based on their socioeconomic background. This system was in place for nearly 1300 years and lasted until the end of the Qing dynasty.5 This century-old civil service administrative selection system profoundly influenced China’s modern-day system and its functions. It also influenced systems in other countries.6 Though the royal test dissolved when Chinese Imperialism ended, the impact of this system, which is deeply rooted in Chinese culture, persists in society today.

Following the Chinese Civil war of 1949, the national government reformed the country’s educational system by borrowing elements of rigor and competitiveness from the traditional royal examination and adopted them into the country’s education system. During the Cultural Revolution era, the education system in China was paralyzed and university education services shut down. After the Chinese Economic Reform began in 1978, the education system resumed following a tumultuous period of ten years, and the government addressed the upfront challenges presented by the radical reform of the education system. It was not only the educational system that was reformed by adopting royal examination elements, but also the selection process of civil administrative servants since 1994.

Government Strategies and Decisions

Since the founding of the PRC, the state’s attitude towards scientific research and its popularization can be divided into three stages of development. In the decade between 1949 and 1959, the government focused on scientific research projects in the infrastructure and defense industries. The PRC’s scientific research cooperated with the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Front became an essential guiding development policy.

From 1978 to 2002, China’s understanding of popular science gradually deepened the reform of the education system. The “Outline of Education Reform and Development in China,” issued in 1993, underscored how primary and secondary schools should change the pattern of “examination-oriented education,” which is the earliest response to the concept of quality education in the central policy text.7 The “Action Plan for the Revitalization of Education for the 21st Century,” issued by the Ministry of Education in 1998, addressed the importance of shaping education by cultivating single scientific research talents in high-quality education.8

Finally, from 2003 to 2020, comprehensive implementation of sustainable universal popular science, quality education, and scientific research became the government’s top priority. The Eleventh, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Five-Year Plans all emphasized the need to fully implement quality education through an effective reduction in academic burdens on primary and secondary school students, comprehensive consideration of students’ abilities, and improvements in students’ employment skills and abilities. This also deepened the reform of the education system and accelerated scientific-practical development policies such as technological innovation and interdisciplinary studies.9

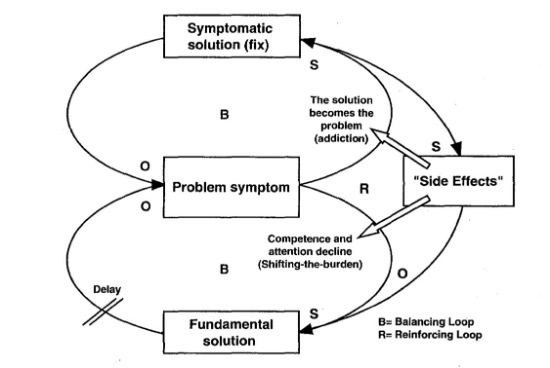

The Double Reduction Policy is a continuation of this government education revolution, which marked a new era for the Chinese education system. However, it differed in its rapid and rigid (rather than incremental) nature. Original governmental education policies were implemented gradually without provoking significant public backlash. By contrast, the Double Reduction Policy acted as a swift method to eliminate the entire private education sector, leveraging nascent education programs such as Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics (STEAM), field trip research, and campus clubs and activities. Like the shifting-the-burden archetype introduced by John Ehrenfeld, the symptomatic solution could be temporarily solved by the quick fix and by the fundamental solution with potential side effects. However, it is unknown whether the solution that the Chinese government implemented is fundamental or another quick fix.10

Figure 1. John R. Ehrenfeld. “Chapter 2. Solving the Wrong Problem: How Good Habits Turn Bad” Sustainability by Design: A Subversive Strategy for Transforming Our Consumer Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 10-21.

Further, according to the “Outline of Action Plan for National Science Literacy (2021-2035),” issued by the State Council on June 3, 2021, President Xi Jinping stressed that scientific and technological innovation and popularization of science are the two directions to realizing innovation and development. Without high-quality and comprehensive education, China will be ill-equipped to undertake a complex transformation from an export-oriented power to a scientific and technological-oriented one. Recent educational data in China shows that only 10% of the population possess high-quality and comprehensive education, while the remaining majority has traditional education.11

Calamity in the Private Education Sector

In 2018, Ministry of Education Officials published a plan for better regulation of off-campus tutoring, demanding that private education companies register with the government and align their curriculum with public schools.12 However, the implementation and compliance of this directive were weak without the firm and did not generate the effective outcomes that top officials had expected.

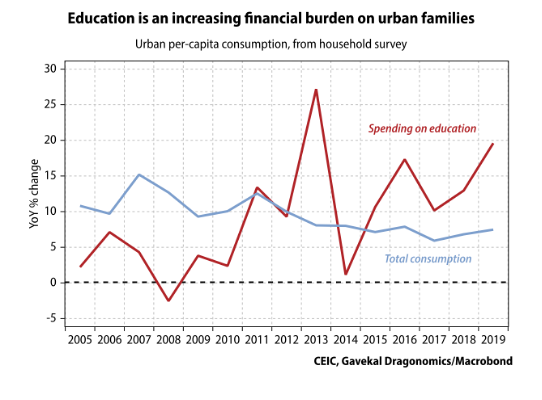

Two events influenced the government’s attitude towards off-campus tutoring, which triggered bankruptcies in the private education sector. First, all students were required to use online education platforms to comply with strict social distancing rules during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, private tutoring took advantage of online education, earning large amounts of money and undergoing rapid expansions.13 The second event was the 2020 population census. The census revealed that China’s population growth rate and fertility rate have dramatically slowed. The root cause of this, as government officials concluded, was the excessive amounts of schoolwork for youth and the resulting financial burdens on parents to pay for additional education expenses. Education has been one of the fastest-growing categories of household spending, rising from 7.5% of the nationwide total in 2013 to 9.5% in 2019, according to the official household survey.14

Figure 2. Ernan Cui. Class Is Over For Tutoring Firms (2021, July 26), Page 2.

To correct this, the government implemented the Double Reduction Policy, with massive crackdowns on private education companies spreading from major cities to rural areas. The economic fallout among the Chinese private education sector was massive.

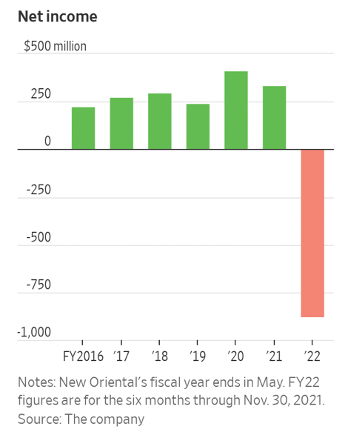

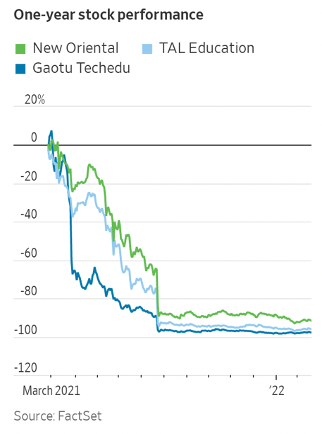

On February 22, 2022, New Oriental Education & Technology Group Inc. reported an $876 million loss for the second half of the 2021 fiscal year, compared with a net profit of about $229 million in the beginning of the same year.15

Figure 3. Dave Sebastian & Anniek Bao. Chinese Tutoring Companies Take Big Financial Hit Amid Crackdown (2022 February 22).

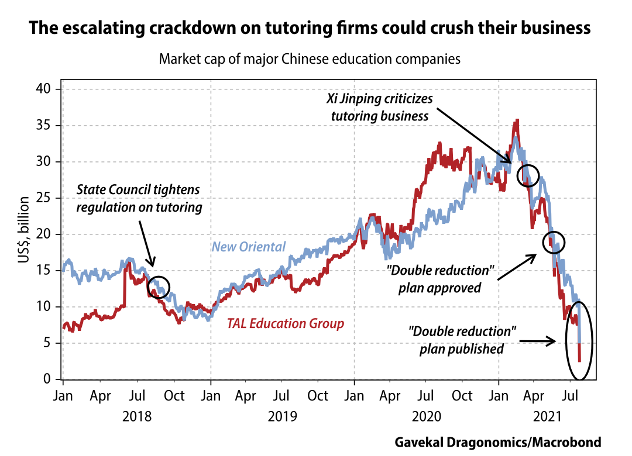

On February 21, 2022, another private education company, TAL Education Group, similarly reported that it lost $99 million in the final quarter of 2021, pushing its net loss in the first nine months of its fiscal year to $1.03 billion. In the preceding year, the company had earned a $53 million profit in the same period.16

These organizations represent two of the major players in the Chinese education sector, whose losses provide a snapshot of the Double Reduction Policy’s industry-wide repercussions. The two companies’ probability timelines reveal how policy influences their supplies and decisions.

Figure 4. Ernan Cui. Class Is Over For Tutoring Firms (2021, July 26), Page 1.

Figure 5. Dave Sebastian & Anniek Bao. Chinese Tutoring Companies Take Big Financial Hit Amid Crackdown (2022, February 22).

Social and Economic Dilemmas for Parents and Students

Parents and students must face new social and economic dilemmas created by the Double Reduction Policy. As the legal channel of receiving tutoring is officially closed, the continued demand of off-campus tutoring and the pressure from severe competition drive up the price of illegal tutoring and increase the time of searching for off-campus opportunities. In addition, the equilibrium of the demand and supply side has been demolished by the Double Reduction Policy. Therefore, the cost will increase on the supply side and generate a huge amount of deadweight loss for the society. With or without off-campus tutoring, students must take highly demanding examinations that determine whether they will be granted admission into China’s top schools and a chance at a promising career. However, the newfound lack of tutoring has left parents unsure of how to guarantee their children’s success. For example, do parents and students who cannot afford at-home tutoring forgo additional homework or after-school tutoring, yet furthering the economic class divisions? Or, do lower-income parents take on other financial burdens to afford at-home tutors, which will allow their children to be able to compete?

Many wealthy families have found workarounds to the Double Reduction Policy, including hiring live-in private tutors to work as full-time nannies and teachers. Providing advancement opportunities to wealthy students increases the risk of decreasing advancement opportunities among middle-class students who may fall behind simply because their parents cannot afford such luxuries.17 This asymmetrical competition may put the education system in further jeopardy.

Comprehensive and high-quality education may also indirectly increase the burden on parents. Newly created education sectors such as STEAM, field trip research, campus clubs, and activities are not comparable with developed economies since they have more funding, concept structure, and time. Concerned about their children receiving low-quality education through these nascent initiatives, parents prefer to spend extra money on extracurricular studies. Competition in the education system is deeply rooted in Chinese culture, which may steer the government’s more holistic approach away from its desired outcomes.

Differences in Family Culture Background and Demographic Population Distribution

In the “Report on Household Education Expenditure in China (2019),” Chinese families were divided into four groups according to their total annual household educational expenditures. High-income families’ average expenditure on off-campus training is 8,824 yuan per year – nearly six times that of the lowest-income group at 1,520 yuan per year. The average off-campus training expenditure of the top five percent of families is 14,372 yuan per year – approximately 20 times that of the lowest five percent of families’ 710 yuan per year spending.18 Within that top five percent are families with higher incomes who spend more on tuition and liberal arts classes, and the gap widens with the increased age of students. In addition, there are significant differences within the high-income group. A possible reason is that, due to budget constraints, low-income families have prioritized investment in their children’s out-of-school education. The high-income group is less constrained and impacts to their children’s investment in out-of-school education are more rooted in cultural, rather than economic, factors.

Family structure is also significant. Data shows that in single-child families, there is likely to be more investment in off-campus education than in multi-child families. In the same one-child family, the only-child girl has more access to extracurricular education opportunities.19 According to the household registration status – a Chinese policy that restricts people from moving regionally – students from rural households are less likely to receive extracurricular tutoring and interest classes. Families of this population, who invested during childhood in more resources for both in-school and off-campus education for their children, are likely to compensate for the poorer quality of in-school education.

Conclusion

The Double Reduction Policy aimed to improve the quality of after-school programs, decrease the amount of homework required of students in compulsory education, cut down on the number of students who needed extracurricular classes outside of school, and accommodate students of varying backgrounds and learning styles.

The legacy and influence of the Double Reduction Policy challenged many families and may jeopardize their children’s futures. The development of on-campus events, clubs, liberal arts studies, and other on-campus activities deserves critical attention. There is a need for reform to persuade parents to favor the public schools’ services instead of off-campus tutoring, presently illegal under the Double Reduction Policy. Furthermore, the recent rise of non-disciplinary sector tutoring may challenge the government’s initial intent in this new educational policy to promote greater education equality and reduce the burden of extra-familial expenses. Lastly, government exams have not changed in their difficulty, yet the new procedure removing after-school tutoring support has drastically elevated students’ and parents’ anxieties. China requires more complementary policies and reforms to achieve the government’s long-term goal of educational equity and reduced familial financial burdens while mitigating its concerns on ongoing education issues, market regulation, and population challenges.

Endnotes

- Minhong Yu 俞敏洪. (2022). Laoyuxianhua丨努力工作,努力学习,努力寻找新的方向!. Wechat article微信公众平台.

- Wendy Ye. “China’s Harsh Education Crackdown Sends Parents and Businesses Scrambling.” CNBC.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council issued the “Opinions on Further Reducing the Burden of Homework and Off-campus Training for Students in Compulsory Education” (中共中央办公厅 国务院办公厅印发《关于进一步减轻义务教育阶段学生作业负担和校外培训负担的意见 》).

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). Notice on Further Clarifying the Scope of Off-campus Training Disciplines and Non-Disciplines in Compulsory Education (教育部办公厅关于进一步明确义务教育阶段校外培训学科类和非学科类范围的通知).

- Zainab. (2022, March 23). Who invented exams? standardized testing creator. The Invented.

- Herrlee G Creel. (March 1974). “Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration”. Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 1(2): 119–136.

- State Council of People’s Republic of China. (1993). Outline of Education Reform and Development in China《中国教育改革和发展纲要》.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (1998 December 24th). Action Plan for the Revitalization of Education for the 21st Century《面向21世纪教育振兴行动计划》

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2006, 2011, 2016). Eleventh Five-Year, Twelfth Five-Year, and Thirteenth Five-Year Plans.

- John R. Ehrenfeld. “Chapter 2. Solving the Wrong Problem: How Good Habits Turn Bad” In Sustainability by Design: A Subversive Strategy for Transforming Our Consumer Culture, 10-21. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2021 June 3rd). Outline of Action Plan for National Science Literacy (2021-2035) 《全民科学素质行动规划纲要(2021-2035)通知》.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2018 February 22). Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China《国务院办公厅关于规范校外培训机构发展的意见》.

- Ernan Cui. (2021, July 26). Class Is Over For Tutoring Firms. Gavekal Dragonomics.

- ibid

- Dave Sebastian & Anniek Bao. Chinese Tutoring Companies Take Big Financial Hit Amid Crackdown (2022, February 22).

- Dave Sebastian & Anniek Bao (2022, February 22). Chinese Tutoring Companies Take Big Financial Hit Amid Crackdown.

- Wenxin Fan. Who Says No Tutors and Less Homework Is Bad? Many Chinese Parents (2022, January 15).

- Yi Wei. Report on Household Education Expenditure in China (2019). ISBN: 9787520154680. Social Sciences Academic Press (CHINA) published.

- ibid