Illustrations by Steve Arnold (used with permission)

Written by Jennifer Thompson

Edited by Chelsea Halstead

Although the full extent of COVID-19’s wreckage remains unknown, devastating effects on health, society, and the economy have already affected reproductive autonomy in the United States. Challenges in gaining access to care, resource scarcities, and economic barriers have nearly all aspects of reproductive health choices, exacerbating a situation that is already difficult for many.[1] The ability to exercise reproductive autonomy within the context of intimate relationships, sex, and family formation is central to our lives and our dignity as human beings, and does not cease during a pandemic.[2]

Previous public health emergencies have demonstrated that because the effects on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) are often not a direct result of a crisis, they often go unrecognized—despite being considered essential, life-saving components of healthcare.[3] The impacts on SRH care cover a wide expanse. A recent Lancet publication reported that past humanitarian crises have demonstrated “reduced access to family planning, abortion, antenatal, HIV, gender-based violence, and mental health care services results in increased rates and sequelae from unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pregnancy complications, miscarriage, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, suicide, intimate partner violence, and maternal and infant mortality.”[4]

Past humanitarian crises have demonstrated “reduced access to family planning, abortion, antenatal, HIV, gender-based violence, and mental health care services results in increased rates and sequelae from unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy complications, miscarriage, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, suicide, intimate partner violence, and maternal and infant mortality”

– The Lancet, 2020

Though the current shock from the pandemic may seem temporary, evidence suggests effects from the pandemic may linger.[5] Moreover, pre-existing inequities are amplified by crises, leaving historically marginalized groups experiencing a greater burden of impact.[6] As the United States continues to fight through this pandemic, it is critical to envision a path where heightened value is placed on preserving and promoting reproductive health and rights as essential components of life.

It is vital that policymakers take quick action to address this potential catastrophe. In the immediate sense, urgent action can support some of the most time-sensitive issues such as access to contraceptive services, abortion care, and safe care related to pregnancy and delivery. In the long-term, understanding the implications of equitable access to SRH allows legislators to take the necessary steps and make decisive and evidence-based actions—securing SRH as a fundamental right and creating a pathway to amend longstanding issues related to inequity. The recent passage of the CARES Act, a $2 trillion federal relief package promising to deliver funding to state and  local governments, healthcare facilities, and businesses, neglected protection or support for sexual and reproductive health rights.[7]

local governments, healthcare facilities, and businesses, neglected protection or support for sexual and reproductive health rights.[7]

As noted by Dr. Herminia Palacio, president and CEO of the Guttmacher Institute, “the path to sound and just policies can be difficult to discern amongst the fog of misinformation and disinformation.”[8] Throughout the negotiations of COVID-19 relief packages, it is important that evidence is used to inform the true state of SRH rights in the U.S. Armed with factual information, state and federal legislators can use the recommendations presented in this paper to take actions to protect and support these fundamental rights. Additionally, these recommendations provide a foundation for constituents to petition their congressional representatives to prioritize and protect reproductive freedoms while promoting SRH. This is by no means an exhaustive list, as many of these issues are longstanding and predate COVID-19.

Inequities in health states and healthcare

Profound inequities regarding health states and healthcare have existed long before COVID-19 and often perpetuate structural and systemic barriers resulting from racism, environmental injustices, gender disparities, and economic inequities.[9][10] Although health disparities are multifactorial, one critical component for addressing these stratified systems of care is through access to comprehensive health insurance.

In the U.S., more than two million low-income individuals remain uninsured as a result of states’ deliberate decisions not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).[11] The majority of individuals affected by this coverage gap have limited family income and unpredictable access to employer-based coverage.[11] Most states which have opted out of Medicaid expansion are in the Southern U.S. and have longstanding histories related to racial health inequalities, by default reinforcing geographic disparities in coverage.[12][13]

Though much of the available data is preliminary, deaths related to COVID-19 are disproportionately high for Black Americans, with evidence suggesting stark disparities in Southern states.[14] A recent analysis by the Washington Post demonstrated that majority-Black counties have three times the rate of infections and almost six times the rate of deaths when compared to majority-White counties nationwide.[15] In Alabama, more than 50% of people killed by COVID-19 were Black, despite making up only 26% of the population, and in Mississippi, Black Americans have accounted for 66% of deaths even though they comprise only 38% of the population.[16]

In addition to disparate health outcomes created by unequal opportunities to access quality healthcare, many people who are insured lack comprehensive coverage. Although ACA Marketplace insurance plans are required to cover FDA-approved contraceptive methods, Medicare,[1] religious employers, and non-profit religious organizations are exempt, which results in coverage gaps.[17][18] Coverage for contraceptive services during a crisis is critical for families who want to avoid pregnancy. Historically, the unintended pregnancy rate for poor women is greater than five times that of higher-income women, though individuals who are able to correctly and consistently use contraceptives have an unintended pregnancy rate of only 5% annually.[19]

Because the Hyde Amendment bans the use of federal funds for abortion care under Medicaid,[2] Medicare, and other federal programs,[3] most individuals pay out of pocket for their abortions.[20] Had the ban been lifted in 2018, over 15.5 million reproductive-age women enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare could have received federal support for abortion coverage.[21] As COVID-19 relief packages are being prepared, Republican lawmakers have demanded that anti-abortion Hyde Amendment language be included in any funding measures. [22][23] Private insurance plans do not guarantee coverage for abortion care either; the Guttmacher Institute notes that as of May 2020, more than half of U.S. states have abortion restrictions on private health plans, including the policies of public employees in 22 states.[24]

Additionally, lapses or inability to access healthcare because of insurance restrictions negatively impacts many other areas of reproductive health, ranging from preventative services for reproductive cancers, to HIV and STI screening and treatment, to transgender and LGBTQIA+ specific care.

The U.S. must improve access to comprehensive health insurance coverage and eliminate discriminatory restrictions through the following actions:

– In the short term, the federal government should incentivize states to expand Medicaid, through already introduced legislation such as Senate Bill 585, or the SAME Act of 2019.

– In addition to funding increased state subsidies to make ACA Marketplace plans more affordable, the federal government should direct states to establish an emergency open enrollment period for persons whose health may have been impacted by COVID-19.

– In the long term, demands for universal health coverage via a single-payer healthcare system that removes insurance companies from the healthcare system must continue to receive support. If states like New York were to pass legislation such as the New York Health Act, it would set the standard for equitable and just healthcare coverage and other states would arguably follow suit.

– Access to SRH services should be expanded to all individuals, regardless of documentation or immigration status.

– All health insurance plans (including those offered through the ACA Marketplace) should be mandated to cover all FDA-approved methods of contraception, including male condoms and vasectomies.

– Congress should expedite the Affordability is Access Act, which would allow birth control pills to be available over the counter without a copayment or prescription.

– Currently, Medicaid, Medicare, and most commercial insurance plans limit reimbursement for prescription refills to once a month, prohibiting many from having an extended supply of medications. Insurance plans should relax restrictions on prescription refills for critical medications, including contraceptives, HIV medications, and other essential drugs.

– To help reduce discriminatory restrictions on insurance coverage of abortion, Congress should eliminate the Hyde Amendment from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) annual appropriations bill.

Resource scarcity and family planning provider shortage and diversion

The COVID-19 response has affected nearly every facet of healthcare delivery and exacerbated already dire clinician shortages in some areas of the country.[25][26] The overwhelming strain on the healthcare system, coupled with clinicians’ decreased capacity to see patients (especially for non-emergency care), has resulted in fewer clinicians providing SRH services.[27] Globally, SRH clinics and providers are known to be the primary source of care and safety net for people of reproductive age.[4] In addition, resource diversion away from SRH to prioritize the pandemic response reduces already threatened funding for sexual and reproductive health.[1]

The 2019 domestic gag rule, which bans federal family planning funding to healthcare providers who perform or refer patients for abortion services, has reduced the Title X network’s capacity by 46% nationwide.[28] Four million people rely on Title X services for access to birth control, reproductive cancer screenings, STI treatment, and more, including two-thirds of whom live under the federal poverty line, and half of whom are uninsured.[29] Since the rule has gone into effect, about 1,000 clinic sites (such as Planned Parenthood) have left the network, significantly reducing the number of family planning providers available to serve communities already strained for resources.[1] Since the implementation of the gag rule, it is estimated that the ability of 1.6 million patients to receive care for contraceptive services alone has been reduced.[28]

Although many reproductive health services can be safely and effectively provided via telehealth— including contraceptive counseling and prescription, medication abortion, STI care, obstetric mental healthcare, and some pregnancy-related care—regulatory barriers persist.[30] Beginning in April 2020, Planned Parenthood committed to providing telehealth services in all 50 states, though their exclusion from Title X funding places limitations on resources available to patients.[31]

To help mitigate the effects of provider diversion and shortage, Congress should promote SRH access by restoring integrity to the Title X family planning program and supporting SRH services through telehealth and other avenues. This can be accomplished through:

– Legislative action to block implementation of the 2019 domestic gag rule and create a pathway for providers and affected clinics to return to Title X network funding.

– Support for widespread implementation of telehealth for SRH providers by encouraging states to eliminate unnecessary barriers to use and reimbursement, including telehealth services related to the provision of medication abortion and expedited partner therapy for STI treatment.

– State legislative efforts that would allow pharmacists to prescribe hormonal contraception, eliminating an additional clinician visit and potential COVID-19 exposure. Ultimately, the goal for hormonal contraception should be targeted at over-the-counter access.

– Protection of the pharmaceutical supply chain. Efforts to bolster the U.S. drug supply in response to COVID-19 must take into account pharmaceutical products related to SRH. These include but are not limited to contraceptive drugs and devices, condoms, drugs used for medication abortion, antibiotics for treating STIs, HIV medications, reproductive cancer screening tools, vaccines, and hormone therapy drugs.

Attempts to implement additional abortion restrictions and advance ideological agendas during a crisis

National abortion data from 2017 suggests that around 70,000 people in the U.S. seek abortion care each month (Palacio, 2020). Throughout the pandemic, some governors and state attorneys have used the COVID-19 crisis to attempt to limit access to abortion care, considering it “nonessential healthcare that can be delayed.”[32] Prominent medical experts and organizations have remained firm on their stance that abortion care is an essential, time-sensitive component of healthcare that cannot be delayed without posing risks to patient safety and well-being.[33]

The legalization of abortion throughout the U.S. in 1973 saw dramatic public health impacts, including decreases in morbidity and mortality nationwide.[34] The availability of safe, legal abortion procedures has reduced the rate of complications from illegal abortions and self-induced abortions[4] to a present-day procedure with associated complications of less than 1%.[34][35] Mortality was also reduced dramatically; in 1965, the number of documented deaths resulting from illegal abortions was just under 200, noted by experts as a likely underestimation.[36] In 1976, the reported number of pregnancy-related deaths due to illegal abortion was two.[36]

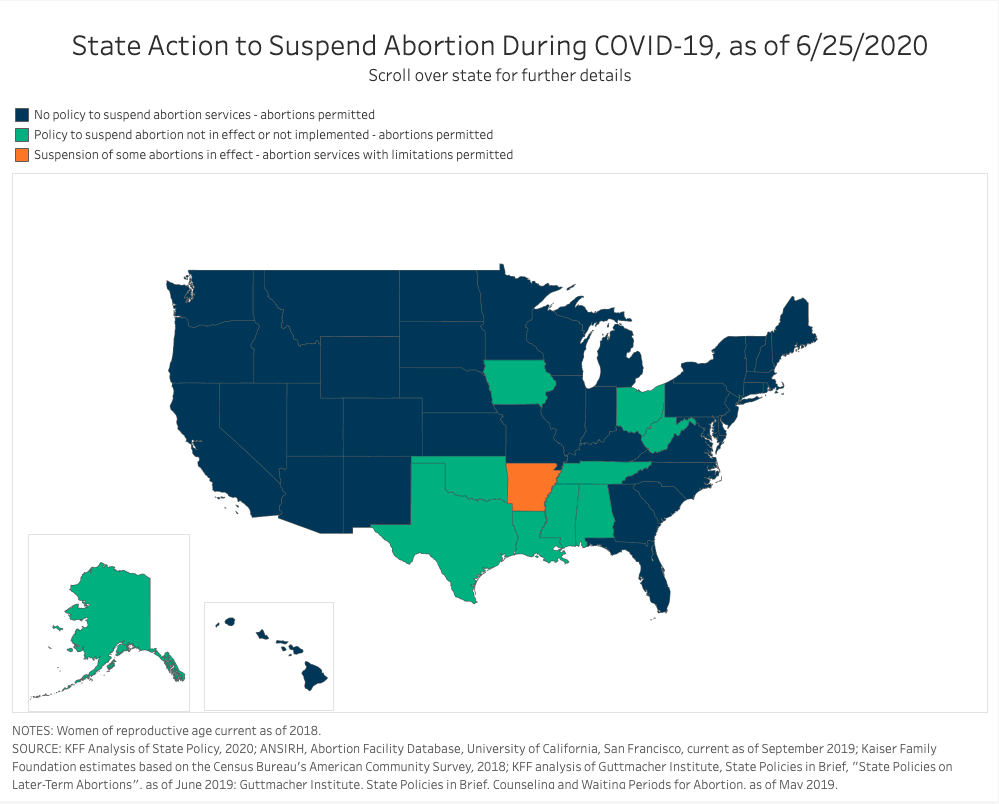

Throughout the pandemic, restriction attempts have been made in Alaska, Iowa, Ohio, West Virginia, Tennessee, Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas (see below). In a recent study, the Guttmacher Institute found that if abortion care in Texas were eliminated, the average driving distance to a clinic would increase from 12 miles to 243 miles, or by 1925%.[8] If upheld, proposed COVID-era abortion restrictions could have lasting effects on SRH access, reversing progress made over the past several decades.

Figure 1. For interactive data viz, see State Action to Suspend Abortion During COVID-19 – Kaiser Family Foundation

To protect the right to abortion care, the following legislative actions should be taken:

-Support the Women’s Health Protection Act, a federal bill that would protect abortion care from state-level abortion bans and medically unnecessary restrictions, such as waiting periods, multiple-trip requirements, and limitations on medication abortion.

-Support the Equal Access to Abortion Coverage in Health Insurance (EACH Woman) Act, which would lift the Hyde Amendment and restore insurance coverage of abortion for individuals enrolled in Medicaid and other federal health insurance programs.

–Repeal legislation that requires parental notice for minors to obtain abortions. This would improve access in 37 states that currently require the involvement of one or both parents as well as a 24-48 hour waiting period prior to a minor obtaining an abortion.

-Enable advanced practice clinicians (such as certified nurse-midwives and nurse practitioners) to provide medical and early surgical abortion care, thereby safely expanding abortion access nationally.

Maternal and Infant Health

Although the direct effects of the COVID-19 virus on pregnancy and maternal health are still unknown, the U.S. has been in the midst of a maternal mortality crisis for a long time.[37] Every year in the United States, about 700 women die as a result of pregnancy-related complications.[38] The U.S. has the highest pregnancy-related mortality ratio[5] (PRMR) of any high-resource country and is the only high-development index nation where the rate continues to rise.[39] The U.S. is also the only nation that expends twice the percentage of gross domestic product on healthcare when compared to other countries, yet has the poorest maternal health outcomes—a performance that has been described as both a national disgrace and a human rights crisis.[40]

Significant racial and ethnic disparities exist within pregnancy-related mortality rates, disproportionately affecting some people more than others. CDC data from 2011 to 2016 indicate that Black non-Hispanic women have three to four times greater likelihood of dying from a pregnancy-related cause than non-Hispanic White women, and American Indian/Alaskan Native women are two to three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than non-Hispanic White women.[42] These differences are thought to be directly related to the effects of racism that Black women (and non-White women) experience when seeking healthcare.[42] The myriad ways racism (interpersonal and structural) pervades society has shown to inhibit access to healthcare and the utilization of support services.[43]

The healthcare delivery system also plays a role in health disparities, as there is a clear overlap between clinical and social systems of power and the reinforcement of persistent inequities. A recent study used statistical models to demonstrate that if Black women gave birth in the same New York City hospitals as White women there could be a possible reduction of severe maternal morbidity by 47%.[44] Conversely, outcomes are not improved in rural areas—maternal mortality is significantly higher in rural areas, where obstetrical providers may not be available.[45] These disparities will persist, if not worsen, given the clinician shortages, decreased availability of resources, and other barriers imposed by the pandemic.

The perspectives taken when examining maternal mortality often provide a distorted picture of why maternal deaths occur. Frequently, a biological and physiological framework is used in lieu of examining the structural and systemic components of this nationwide pathology. Of the pregnancy-related deaths that occur in the U.S each year, it is estimated that 60% are preventable.[42] There are several postulated reasons for U.S. outcomes being so far behind other developed countries including: lack of critical investment in social determinants of health which influence health outcomes, insignificant actions from healthcare leadership to dismantle structural racism and improve health disparities, and government failure to collect accurate data or study maternal deaths in order to understand how they could be prevented.[46][47]

To prevent the further deterioration of maternal and newborn health, legislators should take the following actions to support access and availability of pregnancy-related care:

– Ensure that tracking and testing are available for pregnant and postpartum women. To better understand the impacts of COVID-19 on pregnancy, funding should be sustained for programs such as the Pregnancy Coronavirus Outcomes Registry. This nationwide study provides real-time data on patients through pregnancy and the postpartum period and intends to better understand the effects of COVID-19 on pregnancy, delivery, and newborn health and well-being.

– Pass the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act to comprehensively address racial disparities in maternity care and fill gaps in existing legislation. Components of this critical legislation are: 12-month postpartum Medicaid coverage, investments in rural maternal health, the promotion of a diverse perinatal workforce, funding for community-based organizations working to improve outcomes for Black women, and investing in social determinants of health.

– Follow the lead of states like New York in establishing COVID-19 maternity task forces to make recommendations on the impact of the virus on pregnancy. In addition, states should examine and accelerate the process for certifying additional birth centers to provide families with safe alternatives to already strained hospitals.

– Continue to support and fund equity in the maternal mortality review process through the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act (PMDA) and related legislation. The PMDA supports states as they improve their tracking systems and investigatory efforts into pregnancy-related deaths via maternal mortality review committees, and it provides care recommendations and strategies to prevent future deaths.

– Families should have access to providers from within their own communities who prioritize primary and preventative care across the lifespan. One way to support this would be to allocate more funding toward scholarships and education for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) healthcare providers. In addition, all healthcare curriculums should equip clinicians with ways to address racism and promote reproductive justice.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed devastating inequities within an already broken system, healthcare has also demonstrated agility and an ability to reorganize within a very short interval—indicating that systemic change is possible. No singular policy exists that will enable all people to exercise reproductive autonomy or narrow today’s significant health disparities. But demanding actionable policy changes now, with an ongoing goal of addressing our nation’s deeply entrenched inequities, will be a starting point for dismantling structural injustices and establishing SRH as a fundamental right.

Resources

- Ahmed, Zara, and Adam Sonfield. “The Covid-19 Outbreak: Potential Fallout for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights.” Guttmacher Institute, March 10, 2020. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2020/03/covid-19-outbreak-potential-fallout-sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights.

- Palacio, Herminia. “Anti-Abortion Groups Are Making COVID-19 an Even Greater Public Health Threat.” Rewire.News, March 30, 2020. https://rewire.news/article/2020/03/30/anti-abortion-groups-are-making-covid-19-an-even-greater-public-health-threat/.

- Wenham, Clare, Julia Smith, and Rosemary Morgan. “COVID-19: The Gendered Impacts of the Outbreak.” The Lancet 395, no. 10227 (March 2020): 846–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2.

- Hall, Kelli Stidham, Goleen Samari, Samantha Garbers, Sara E Casey, Dazon Dixon Diallo, Miriam Orcutt, Rachel T Moresky, Micaela Elvira Martinez, and Terry McGovern. “Centring Sexual and Reproductive Health and Justice in the Global COVID-19 Response.” The Lancet 395, no. 10231 (April 2020): 1175–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30801-1.

- Scott, Dylan. “4 Aftershocks of the Coronavirus Pandemic That Will Be Felt for Years.” Vox, May 11, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/5/11/21254892/coronavirus-us-economy-primary-health-care-insurance.

- Kantamneni, Neeta. “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Marginalized Populations in the United States: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, May 2020, 103439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103439.

- Ahmed, Zara, Ruth Dawson, Megan K. Donovan, Leah H. Keller, and Adam Sonfield. “Nine Things Congress Must Do to Safeguard Sexual and Reproductive Health in the Age of COVID-19.” Guttmacher Institute, April 7, 2020. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2020/04/nine-things-congress-must-do-safeguard-sexual-and-reproductive-health-age-covid-19.

- Palacio, Herminia, Zara Ahmed, Ann Biddlecom, Elizabeth Nash, and Rachel Jones. “Protecting Reproductive Rights During the COVID-19 Crisis.” Webinar, May 7, 2020.

- Chotiner, Isaac. “The Interwoven Threads of Inequality and Health.” The New Yorker, April 14, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/the-coronavirus-and-the-interwoven-threads-of-inequality-and-health.

- Perritt, Jamila. “To Protect Abortion Rights for All, We Must Address the Inequities in Care That Are Killing Us.” Rewire.News, April 27, 2020. https://rewire.news/article/2020/04/27/abortion-rights-inequities-care-killing-us/.

- Orgera, Kendal, and Rachel Garfield. “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States That Do Not Expand Medicaid.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog), January 14, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/.

- Artiga, Samantha, and Kendal Orgera. “Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity since the Aca, 2010-2018.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 5, 2020. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/.

- KFF. “Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog), April 27, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/.

- Chotiner, Isaac. “The Interwoven Threads of Inequality and Health.” The New Yorker, April 14, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/the-coronavirus-and-the-interwoven-threads-of-inequality-and-health.

- Thebault, Reis, Andrew Ba Tran, and Vanessa Williams. “The Coronavirus Is Infecting and Killing Black Americans at an Alarmingly High Rate.” Washington Post, April 7, 2020, sec. National. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-shows/.

- “COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Race Ethnicity.” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 21, 2020. https://public.tableau.com/profile/kaiser.family.foundation#!/vizhome/FinalCOVID-19CasesandDeathsbyRaceEthnicity/COVID-19EthnicityOverview.

- HealthCare.gov. “Birth Control Benefits and Reproductive Health Care Options in the Health Insurance Marketplace.” Accessed May 10, 2020. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/birth-control-benefits/.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. “Private and Public Coverage of Contraceptive Services and Supplies in the United States.” Women’s Health Policy, July 10, 2015. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/private-and-public-coverage-of-contraceptive-services-and-supplies-in-the-united-states/.

- Sonfield, Adam, Kinsey Hasstedt, and Rachel Benson Gold. “Moving Forward: Family Planning in the Era of Health Reform.” Guttmacher Institute, January 27, 2016.

- Jones, Rachel K., Ushma D. Upadhyay, and Tracy A. Weitz. “At What Cost? Payment for Abortion Care by U.S. Women.” Women’s Health Issues 23, no. 3 (May 2013): e173–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2013.03.001.

- Salganicoff, Alina, Laurie Sobel, and Amrutha Ramaswamy. “The Hyde Amendment and Coverage for Abortion Services.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog), January 24, 2020. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/the-hyde-amendment-and-coverage-for-abortion-services/.

- Washington, Jessica. “House Republicans Tried to Capitalize on Coronavirus to Sneak Anti-Abortion Language into Law.” Mother Jones (blog), March 13, 2020. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2020/03/house-republicans-tried-to-capitalize-on-coronavirus-to-sneak-anti-abortion-language-into-law/.

- Hoonhout, Tobias. “Sasse Rips Pelosi for Trying to Smuggle Hyde Amendment Loophole into Coronavirus Package.” National Review (blog), March 13, 2020. https://www.nationalreview.com/news/sasse-rips-pelosi-for-trying-to-smuggle-hyde-amendment-loophole-into-coronavirus-package/.

- State Laws and Policies. “Regulating Insurance Coverage of Abortion.” Guttmacher Institute, May 1, 2020. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/regulating-insurance-coverage-abortion.

- Keesara, Sirina, Andrea Jonas, and Kevin Schulman. “Covid-19 and Health Care’s Digital Revolution.” New England Journal of Medicine, April 2, 2020, NEJMp2005835. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005835.

- Health Resources & Services Administration. “Shortage Areas,” May 10, 2020. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas.

- Burkhart, Julie. “Coronavirus Is Hindering Access to Reproductive Health Care.” The Hill, March 30, 2020. https://thehill.com/opinion/civil-rights/490121-covid-19-is-hindering-access-to-reproductive-health-care.

- Dawson, Ruth. “Trump Administration’s Domestic Gag Rule Has Slashed the Title X Network’s Capacity by Half.” Guttmacher Institute, February 4, 2020. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2020/02/trump-administrations-domestic-gag-rule-has-slashed-title-x-networks-capacity-half.

- Planned Parenthood Action Fund. “What Is the Trump-Pence Administration’s “Gag Rule?” Planned Parenthood, March 7, 2019. https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/blog/what-is-the-domestic-gag-rule.

- Weigel, Gabriela, Brittni Frederiksen, Usha Ranji, and Alina Salganicoff. “Telemedicine in Sexual and Reproductive Health.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog), November 22, 2019. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/telemedicine-in-sexual-and-reproductive-health/.

- Abrams, Abigail. “Planned Parenthood Is Expanding Telehealth amid COVID-19.” Time, April 14, 2020. https://time.com/5820326/planned-parenthood-telehealth-coronavirus/.

- Rewire.News. “Abortion Access during COVID-19, State by State,” April 14, 2020. https://rewire.news/article/2020/04/14/abortion-access-covid-states/.

- ACOG. “Joint Statement on Abortion Access during the COVID-19 Outbreak.” American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, March 18, 2020. https://www.acog.org/en/News/News Releases/2020/03/Joint Statement on Abortion Access During the COVID 19 Outbreak.

- Cates, Willard, David Grimes, and Kenneth Schultz. “The Public Health Impact of Legal Abortion: 30 Years Later.” Guttmacher Institute, January 27, 2005. https://www.guttmacher.org/journals/psrh/2003/01/public-health-impact-legal-abortion-30-years-later.

- Upadhyay, Ushma D., Sheila Desai, Vera Zlidar, Tracy A. Weitz, Daniel Grossman, Patricia Anderson, and Diana Taylor. “Incidence of Emergency Department Visits and Complications After Abortion:” Obstetrics & Gynecology 125, no. 1 (January 2015): 175–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000603.

- Benson Gold, Rachel. “Lessons from Before Roe: Will Past Be Prologue?” Guttmacher Institute, September 22, 2004. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03/lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue.

- CDC. “Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/pregnancy-breastfeeding.html.

- CDC. “Maternal Mortality.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 4, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/index.html.

- Kassebaum, Nicholas J, Ryan M Barber, Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Lalit Dandona, Peter W Gething, Simon I Hay, Yohannes Kinfu, et al. “Global, Regional, and National Levels of Maternal Mortality, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.” The Lancet 388, no. 10053 (October 2016): 1775–1812. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31470-2.

- Clark, Steven, and Michael Belfort. “The Case for a National Maternal Mortality Review Committee:” Obstetrics & Gynecology 130, no. 1 (July 2017): 198–202. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002062.

- CDC. “Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 4, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm.

- Simpson, Kathleen Rice. “Maternal Mortality in the United States:” MCN, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 44, no. 5 (2019): 249. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000560.

- “Racial Disparities in Birth Outcomes and Racial Discrimination as an Independent Risk Factor Affecting Maternal, Infant, and Child Health: An Executive Summary of Existing Research.” Midwives Alliance of North America [MANA], The International Center for Traditional Childbearing & The International Cesarean Awareness Network, 2015. https://mana.org/pdfs/ExecutiveSummary-Race-2015.pdf.

- Howell, Elizabeth A., Natalia N. Egorova, Amy Balbierz, Jennifer Zeitlin, and Paul L. Hebert. “Site of Delivery Contribution to Black-White Severe Maternal Morbidity Disparity.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 215, no. 2 (August 2016): 143–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.007.

- Maron, Dina Fine. “Maternal Health Care Is Disappearing in Rural America.” Scientific American. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/maternal-health-care-is-disappearing-in-rural-america/.

- Hardeman, Rachel R., Eduardo M. Medina, and Rhea W. Boyd. “Stolen Breaths.” New England Journal of Medicine, June 10, 2020, NEJMp2021072. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2021072.

- Martin, Nina. “‘Landmark’ Maternal Health Legislation Clears Major Hurdle.” ProPublica. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www.propublica.org/article/landmark-maternal-health-legislation-clears-major-hurdle.

- Medicare, a federal insurance program typically thought of as an insurer for people aged 65 and over also provides insurance to women ages 18–44 with chronic conditions and disabilities. ↑

- Except under limited circumstances including rape, incest, or life endangerment. ↑

- Federal programs include Indian Health Service and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Similar language has been incorporated into other federal programs such as the Peace Crps, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, the military’s TRICARE program, and federal prisons.[21] ↑

- Although estimates through the 1950’s and 1960’s vary widely, a commonly accepted measurement in available literature projected illegal (or self-induced) abortions prior to Roe v. Wade at about 800,000 per year, nationally.[36] ↑

- Defined as the number of pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births per year, often used interchangeably with maternal mortality ratio. ↑