Source: Michael Longmire|Unsplash

Written by James Warren

Edited by Tiffany Agard and Stan Njugu

America – Living Faster, Dying Younger

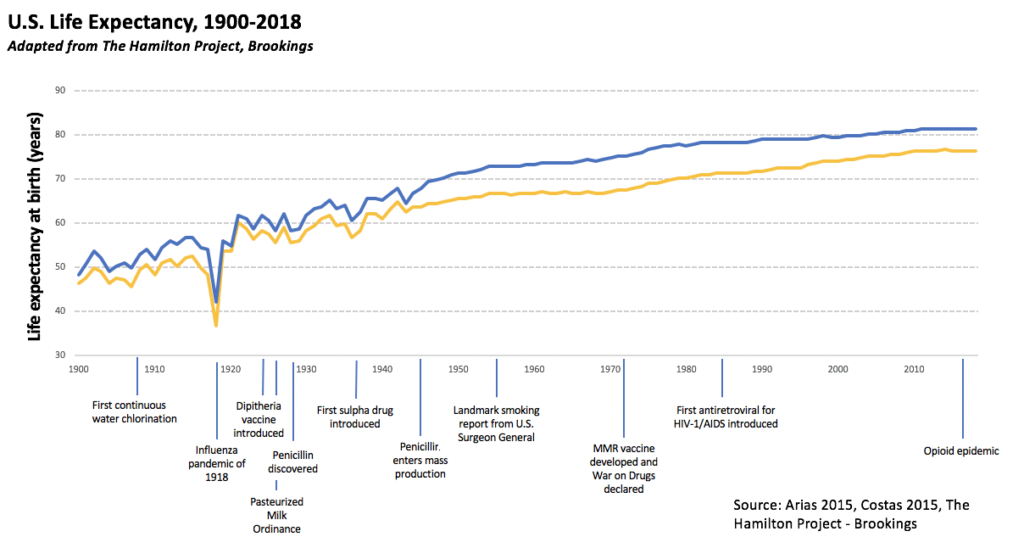

In 2018, for the first time since 2014, life expectancy in the United States rose. The life expectancy is now “78.7 years for the total U.S. population — an increase of 0.1 years from 78.6 years in 2017.”[17] This might beg the question: isn’t a yearly rise in life expectancy normal in the U.S.? Typically, life expectancy rises each year. However, the U.S. saw a decline in life expectancy in 2015, the first time since 1993.[4] Researchers saw the same decline in 2016 and 2017, making 2015-2017 the longest run of life expectancy decline since 1915-1918, a period which experienced a World War and a flu pandemic (Figure 1).[3];[4]

Figure 1: Life expectancy trends from 1900-2018[11],[26],[15]

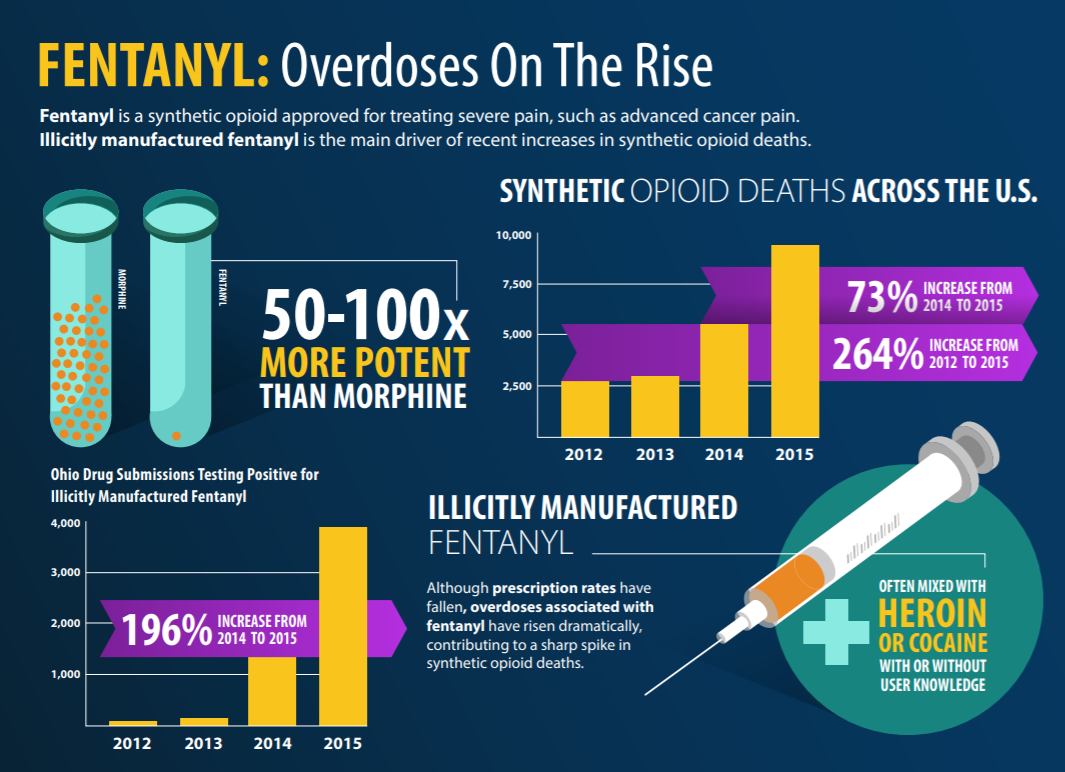

Life expectancy decline is, of course, of concern to healthcare professionals who, in a 2019 Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) study, found that suicides and drug overdoses are largely to blame for the decrease.[10] Overdose is, “a biological response to when the human body receives too much of a substance or mix of substances” and, in the case of opioids, often results in death.[10] The JAMA study states “Between 1999 and 2017, midlife mortality from drug overdoses increased by 386.5% (from 6.7 deaths/100 000 to 32.5 deaths/100 000).”[10] Drug overdose rates rose 9.6% from 2016-2017.[12] 67.8% of overdoses resulted from opioid use.[17] This rise in overdoses was exacerbated even further by the prevalence of a deadly drug called fentanyl, which is 50-100 times more potent than morphine.[18] Most fentanyl is illicitly produced and is often mixed with heroin with or without the user’s knowledge.[18]

Figure 2: A CDC summary sheet on Fentanyl [18]

Figure 3: A lethal dose of Fentanyl [19]

Data and Medicine:

The high lethality of fentanyl requires a medical response capable of reducing the threat of the opioid crisis. There is a growing body of research supporting various addiction mitigation and recovery programs as well as medications – such as Naloxone, Methadone, or Buprenorphine – to combat overdose and addiction. Studies from the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the New York Academy of Medicine have shown that clean needle exchanges are a possible way to reduce risk and promote recovery.[18];[19] Needle exchange programs, where individuals can receive sterile injection equipment, have been shown to result in a reduction in risk of blood-borne diseases, such as HIV or Hepatitis B and C.[20] A study published in the Journal of Urban Health titled “Needle-Exchange Attendance and Health Care Utilization Promote Entry into Detoxification” suggests that needle exchanges actually promote entry into detoxification and recovery programs by acting as a bridge between injection drug users and medical providers.[21][22]

One of the main problems with implementing needle exchange programs is that it cuts against the general public’s intuition about what risk mitigation approaches would be most effective. After all, why would giving individuals struggling with addiction a chance at lower-risk injection be a good thing?

Opponents of needle exchange programs argue that they decrease risk and therefore incentivizes drug abuse via syringe. Frank McNulty, former Colorado House Speaker, who voted against a clean needle exchange bill in 2010 said, “In my opinion, having needle exchange programs only encourages the use of illegal drugs. You are putting the tool out on the street which encourages the use of this illegal drug.”[23] However, a meta-analysis published in 2019 in the Journal of Behavioral Health indicated that needle exchange programs reduce risk and overall drug use.[24] While this paper does acknowledge the inconsistent research methods (for instance, some studies used theoretical approaches to treatment and others did not) used by those studying needle exchange programs, it offers hope that this intervention may be effective for helping those affected by addiction.[25]

Drugs called “opiate antagonists” can reverse overdose and aid in recovery. Programs which increase the availability of opiate antagonists could help reduce the risk of death by overdose.[26] Naltrexone, for instance, is one opiate antagonist which can be used to help patients recover, and is reported in the peer-reviewed medical journal, Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, to be “safe, associated with few side effects, and clearly blocks the reinforcing properties of heroin and other opiates.”[5] Furthermore, Naloxone, an opiate antagonist used on someone who is overdosing, is a “non-addictive, life-saving drug that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose when administered in time.”[5];[21] Opiate antagonists are therefore effective for risk management and have the ability to help individuals struggling with addiction in their recovery.

The Wild West of Opioid Policy

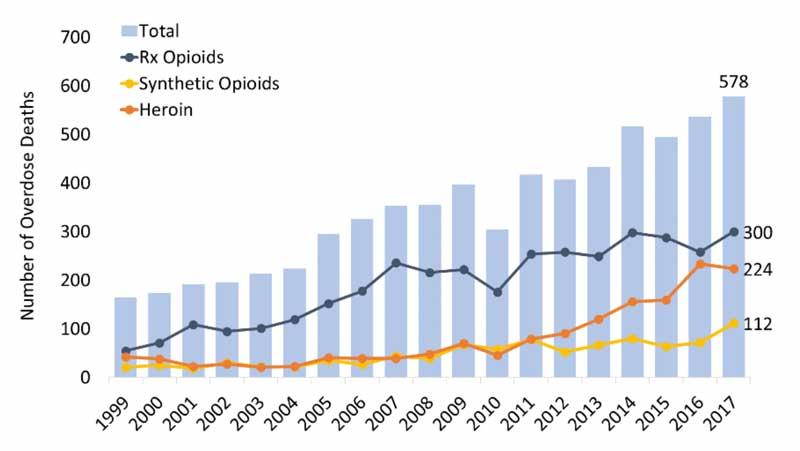

Every state in the U.S. is affected by the opioid crisis.[16] Although Colorado is not the epicenter of the crisis, the numbers of overdoses in Colorado are sobering. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment reports that “from 2000-2016, 4,927 Coloradans have lost their lives to the opioid overdose epidemic.”[23] From 2017 to 2018, the state saw 1,121 deaths due to opioid overdose.[17];[24] Among opioids, “the greatest rise occurred among heroin-involved deaths, with a nearly fivefold increase from 46 cases in 2010 to 224 cases in 2017,” while overdose deaths from fentanyl and other synthetic opioids increased to 112.[24]

Figure 4: Opioid deaths in Colorado[35]

In response, Colorado enacted legislation intending to lessen the effects of the opioid crisis. The legislation took steps towards lowering maximum prescribed doses (decreasing pill count between refills, for instance) for morphine equivalents (Milligram Morphine Equivalents, or MMEs, are a common metric for expressing opioid potency) which is intended to decrease the total amount of addicted individuals by stopping addiction before it begins, and increasing healthcare education programs.[25] These programs, partnered with other effective treatments such as Medication Assisted Treatment, which allow physicians to provide weaker opioids such as methadone to ease the transition to a drug-free life, have allowed Colorado to have more-robust healthcare options for those struggling with opioid addiction than other states.[25] Even so, the opioid epidemic is powerful enough that the state’s medical workers are ill-equipped to provide adequate treatment for those struggling with opioid addiction, and is in need of more tools to combat the crisis.

House Bill 20-1065, subtitled “Concerning Measures to Reduce the Harm Caused by Substance Use Disorders”, was introduced to the General Assembly of Colorado in January of 2020. This bill helps provide treatment for opioid addiction and enables insurance companies and physicians to accelerate recovery.[20] The bill includes a requirement for insurance carriers to reimburse hospitals for providing opiate antagonists upon discharge.[20] Further, the bill increases access to clean syringes (by making them available at pharmacies and eliminating the need for the local board of health approval on clean needle exchanges run by hospitals or nonprofits), extends protections for those who attempt to save someone from overdose by the administration of an opiate antagonist, and provides funds for harm reduction grant programs.[20] The policies enumerated in this bill are backed by a growing body of research, supported by the Center for Disease Control and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and would support the healthcare system as it confronts the enormous challenge of opiate addiction and overdose.[28]

Conclusion

The recent uptick in life expectancy across the United States is a hopeful moment in a period characterized by a falling life expectancy, but without legislative action addressing the opioid epidemic, the nation risks repeating the pattern. According to the American Medical Association, “Colorado has implemented meaningful reforms in response to the opioid epidemic.”[27] Policymakers must continue to support best practices in response to more addictive and deadly drugs, such as fentanyl. HB 20-1065 proposes policies that would employ recommendations from the healthcare community and equip healthcare providers with the tools they will need in order to effectively combat the opioid crisis. This bill alone is not a panacea, but legislation which employs the recommendations of healthcare professionals, such as HB 20-1065, recognizes the opioid crisis for what it is – a public health crisis.

Works Cited

1. Frakt, Austin. “Politics Are Tricky but Science Is Clear: Needle Exchanges Work.” The New York Times. The New York Times, September 5, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/05/upshot/politics-are-tricky-but-science-is-clear-needle-exchanges-work.html.

2. Ling, Walter, Larissa Mooney, and Li-Tzy Wu. “Advances in Opioid Antagonist Treatment for Opioid Addiction.” The Psychiatric clinics of North America. U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4178977/.

3. Smith, David W. E., and Benjamin S. Bradshaw. “Variation in Life Expectancy during the Twentieth Century in the United States.” Demography 43, no. 4 (2006): 647–57. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0039.

4. Solly, Meilan. “U.S. Life Expectancy Drops for Third Year in a Row, Reflecting Rising Drug Overdoses, Suicides.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, December 3, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/us-life-expectancy-drops-third-year-row-reflecting-rising-drug-overdose-suicide-rates-180970942/.

5. Stotts, Angela L, Carrie L Dodrill, and Thomas R Kosten. “Opioid Dependence Treatment: Options in Pharmacotherapy.” Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. U.S. National Library of Medicine, August 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2874458/#S13title.

6. Strathdee, S A, D D Celentano, N Shah, C Lyles, V A Stambolis, G Macalino, K Nelson, and D Vlahov. “Needle-Exchange Attendance and Health Care Utilization Promote Entry into Detoxification.” Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. Springer-Verlag, December 1999. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10609594.

7. Vidourek, Rebecca, Keith King, Robert Yockey, Kelsi Becker, and Ashley Merianos. “Straight to the Point: A Review of the Literature on Needle Exchange Programs in the United States.” Journal of Behavioral Health, no. 0 (2019): 1. https://doi.org/10.5455/jbh.20181023074620.

8. Whitney, Eric. “’Everything But the Dope’.” Colorado Public Radio. Colorado Public Radio, June 30, 2019. https://www.cpr.org/show-segment/everything-but-the-dope/.

9. Wodak, Alex, and Annie Cooney. “Do Needle Syringe Programs Reduce HIV Infection among Injecting Drug Users: a Comprehensive Review of the International Evidence.” Substance use & misuse. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16809167.

10. Woolf, Steven H., and Heidi Schoomaker. “Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the United States, 1959-2017.” Jama 322, no. 20 (2019): 1996. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.16932.

11. Hamilton Project. “The Changing Landscape of American Life Expectancy” Accessed February 12, 2020. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/the_changing_landscape_of_american_life_expectancy.

12. National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Colorado Opioid Summary.” NIDA, March 30, 2019. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-summaries-by-state/colorado-opioid-summary.

13. National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Syringe-Exchange Programs Are Part of Effective HIV Prevention.” NIDA, December 1, 2016. https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2016/12/syringe-exchange-programs-are-part-effective-hiv-prevention.

14. “1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 20, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https://www.cdc.gov/features/1918-flu-pandemic/index.html.

15. “CDC Director’s Media Statement on U.S. Life Expectancy.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, November 29, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/s1129-US-life-expectancy.html.

16. “The Changing Opioid Epidemic: State Trends, 2000-2016.” SHADAC, March 5, 2020. https://www.shadac.org/news/changing-opioid-epidemic-state-trends-2000-2016.

17. “Drug Overdose Deaths.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 27, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html.

18. “Fentanyl.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 31, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/fentanyl.html.

19. “Fentanyl.” DEA, 2 July 2018, www.dea.gov/galleries/drug-images/fentanyl.

20. “Harm Reduction Substance Use Disorders.” Harm Reduction Substance Use Disorders | Colorado General Assembly. Accessed February 12, 2020. https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb20-1065.

21. “Reverse Overdose to Prevent Death.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 28, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prevention/reverse-od.html.

22. “Overdose: What Is It and How Does It Happen?” Addiction Center. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/overdose/.

23. “Overdose Prevention.” Department of Public Health and Environment, February 7, 2020. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdphe/opioid-prevention.

24. “Opioid Crisis in Colorado: The Office of Behavioral Health’s Role, Research and Resources.” Department of Human Services, January 16, 2020. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdhs/opioid-crisis-colorado-office-behavioral-healths-role-research-and-resources.

25. “Pain Management Resources and Opioid Use.” Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, December 26, 2019. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/hcpf/pain-management-resources-and-opioid-use.

26. “Products – Data Briefs – Number 355 – January 2020.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db355.htm.

27. “Study of Colorado’s Efforts to Reverse Opioid Epidemic.” American Medical Association, January 16, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/study-colorado-s-efforts-reverse-opioid-epidemic.

28. “Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) FAQs.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 23, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/ssp/syringe-services-programs-faq.html.