Graphic by Maralmaa Munkh-Achit

Written by Jordan Perras

Edited by Sonali Uppal

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a federal moratorium on residential evictions in early 2020 to lessen the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Public health officials at the CDC and other leading federal agencies hypothesized that those evicted are at a greater risk of catching and spreading COVID-19. Critical public health guidelines from the same agency, such as avoiding crowded areas, physical distancing, and regular, vigorous handwashing, were nearly impossible to adhere to for those living in shelters or temporary or overcrowded spaces. Continuing residential evictions through the economic turmoil caused by the pandemic would have drastically increased the number of people living in those unsafe situations.

In addition to the federal response, many states and local jurisdictions also issued eviction moratoria with varying degrees of restrictions. The economic fallout of the pandemic was staggering, particularly in the uncertainty of early 2020. Various lockdowns and restrictions on businesses led to a skyrocketing unemployment rate in the early aughts of the pandemic, and many families quickly fell behind on rent payments. Record numbers of Americans filed for unemployment insurance, as unemployment reached rates as high as fourteen percent, and over twenty million renters reported losing income as a result of the pandemic [1]. An estimated 30-40 million Americans were at risk of eviction due to nonpayment of rent, representing approximately one-third of American renters [2]. In the initial order, CDC also acknowledged that those Americans who are at the most significant risk of being evicted are those for whom COVID-19 is particularly lethal.

Despite the uneven application of the order and the backlash from states and landlords, the moratoria were largely successful. Researchers concluded that the moratoria were successful risk mitigation measures for limiting the spread of COVID-19 and avoiding evictions across the country. Over 2.5 million evictions were avoided, and the eviction filing rate was halved during the period the moratoria were in effect [3].

Eviction Overview

Despite being a legal practice related to financial health and housing stability, evictions have long been proven to lead to adverse health outcomes. These negative outcomes can include higher mortality rate, respiratory conditions, high blood pressure, poor self-rated general health, coronary heart disease, sexually transmitted infections, drug use, depression, anxiety, mental health hospitalization, exposure to violence, and suicide [1]. Additionally, evictions can result in adverse outcomes for women and children (physical and sexual assault, pre-term pregnancies, lead poisoning, academic decline, decreased life expectancy, low birth rate, and lead poisoning), exposure to sub-standard living conditions (lead, mold, poor ventilation, pests, infestations, crowding), and barriers to livelihood (failing credit scores, unemployment, rental instability, homelessness, inability to access social services) [1].

Further, evictions disproportionately affect renters of color; researchers found that non-White renters faced eighty percent of evictions from 1991 to 2002 [1]. The disparity continues today. Pre-2020, the Eviction Lab’s extensive data found that the share of Black renters (22% in the reviewed sites) received 35% of eviction filings [3]. Unsurprisingly, this trend continued during the pandemic, with Black renters receiving 33% of filings [3]. Black women are particularly at risk, with 20% of Black female renters experiencing eviction during their lifetime relative to 8.3% of Hispanic/Latinx women and 6.7% of White women [1]. While more likely than their white peers to be evicted, Black Americans also face more severe health outcomes related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first six months of the pandemic, Black Americans died at twice the rate of non-Hispanic Whites [1].

Most frustrating, evictions are typically initiated for small debts; researchers found that average filings involve failure to pay one or two months’ rent and involve less than $600 in rental debt [1]. There are also broader societal costs because those who have been evicted are more likely to need emergency shelter and re-housing, use in-patient and emergency medical services, require child welfare services, and experience the criminal legal system [1].

Why did the CDC Address Evictions?

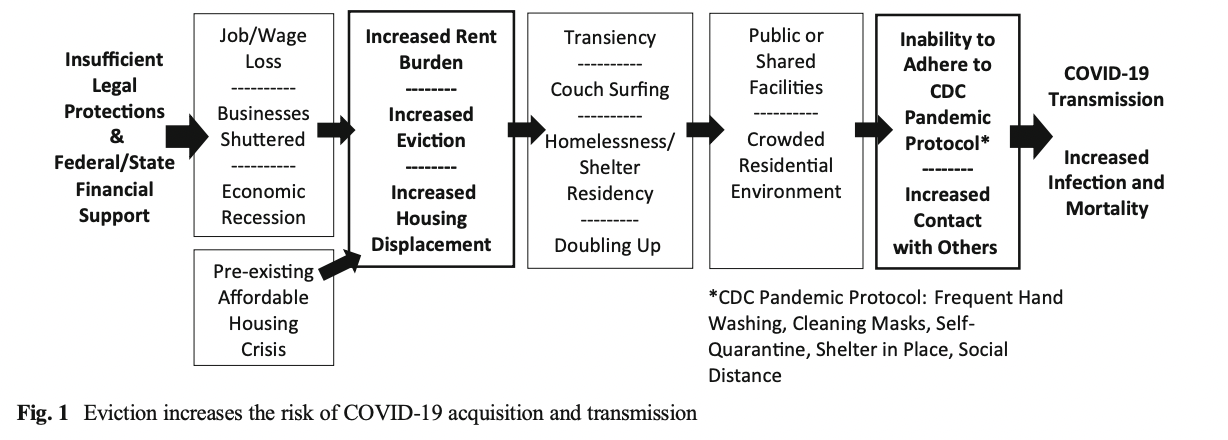

At first glance, it is not necessarily clear why the CDC chose to implement an order related to housing. Yet top researchers at the CDC believed that limiting evictions, specifically, would curb the spread of COVID-19. In addition to the adverse health outcomes outlined above, evictions increase the spread of infectious diseases in general. After being evicted, many renters rely on shelters, doubling up with other friends or family, or encampments of people experiencing homelessness. In some states, homeless shelters are only required to provide 25 square feet of space per person, a situation where social distance is nearly impossible [1]. Each of these situations results in close contact with more people and reduces the likelihood of adhering to the CDC’s own guidelines of social distancing, handwashing, etc. Being in these situations and settings also increases the risk of contracting an infectious disease, particularly one of a respiratory nature such as COVID-19. Research has shown that adding as few as two new members to a household can as much as double the risk of illness [1]. In addition, those in unstable living conditions and those at risk of eviction are likely employed in occupations in which they cannot work from home, leading to a higher risk of exposure to any type of illness [1].

Figure 1: Eviction increases the risk of COVID-19 acquisition and transmission [1].

The CDC aimed to give Congress adequate time to pass rental assistance programs for renters and mortgage assistance programs for landlords by halting evictions. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed in March 2020, included Community Development Block Grants and the Coronavirus Relief Fund [1]. However, funding through the CARES Act ran out quickly, in some cases expiring within minutes. Also, in 2020, Congress passed stimulus checks as a short-term economic stimulus measure and eventually passed the Emergency Relief Act (ERA) in late 2021. In October 2021, the ERA provided $25 billion in discretionary funding for states and localities to implement rental assistance programs [4]. Ensuring that Americans were able to remain in their existing living situations was of critical importance to federal leaders.

CDC Moratorium Details

The initial federal moratorium, Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions to Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19, was issued on September 4, 2020 [5]. The order was initially intended to expire in December of that year, but it was eventually extended four times: on December 27, 2020, January 29, 2021, March 28, 2021, and June 24, 2021, before expiring on July 31, 2021 [3]. The order was issued under the authority of Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC 264) and 42 CFR 70.2 [5]. The language of the original CDC announcement clearly articulates the rationale behind the order and its intended use as a pandemic risk-mitigation measure:

In the context of a pandemic, eviction moratoria—like quarantine, isolation, and social distancing—can be an effective public health measure utilized to prevent the spread of communicable disease. Eviction moratoria facilitate self-isolation by people who become ill or who are at risk for severe illness from COVID-19 due to an underlying medical condition. They also allow State and local authorities to more easily implement stay-at-home and social distancing directives to mitigate the community spread of COVID-19. Furthermore, housing stability helps protect public health because homelessness increases the likelihood of individuals moving into congregate settings, such as homeless shelters, which then puts individuals at higher risk to COVID-19. The ability of these settings to adhere to best practices, such as social distancing and other infection control measures, decreases as populations increase. Unsheltered homelessness also increases the risk that individuals will experience severe illness from COVID-19.[5]

WHAT DID THE MORATORIA DO?

The moratoria temporarily halted residential evictions for nonpayment of rent; evictions of commercial properties were not impacted. Despite the federal moratoria, local interpretation and enforcement of the order varied, primarily driven by variations in local restrictions. Further, the National Low Income Housing Coalition acknowledged the moratoria did not remove landlords’ rights to terminate leases if a tenant conducts criminal activity on the property; threatens the health or safety of other residents; damages or poses an immediate and significant risk of damage to the property; violates applicable building codes, health ordinances, or other regulations related to health and safety; and violates any contractual obligation other than the timely payment of rent, late fees, penalties, or interest [6]. Additionally, residents were required to declare their claim to the moratoria’s protections to their landlords, who could continue to challenge such declarations and continue court filings [3]. The power discrepancy extends to legal representation as well; fewer than 10% of residents fighting evictions have legal representation, up against 90% of landlords who do [1].

Qualifying to be protected by the order was no small feat. While the protections granted by the initial order were broader, the 2021 extensions had more stringent requirements. The National Low Income Housing Coalition summarized qualification requirements:

To qualify, an individual must 1) be a “tenant, lessee, or resident of a residential property” and 2) provide a signed declaration to their landlord stating that they:

- Expect to earn no more than $99,000 annually in 2021 (or no more than $198,000 jointly), or were not required to report income in 2020 to the IRS, or received an Economic Impact Payment in 2020 or 2021 or receive SNAP, TANF, SSI, or SSDI benefits;

- Are unable to pay rent in full or make full housing payments due to loss of household income, loss of compensable hours of work or wages, lay-offs, or extraordinary out-of-pocket medical costs;

- Live in a US county experiencing substantial or high rates of community transmission of COVID-19;

- Are making their best efforts to make timely partial payments as close to the full rental/housing payment as possible and to obtain all available government assistance for rent or housing;

- Would likely become homeless, need to live in a shelter, or need to move in with another person (aka live doubled-up) because they have no other housing options;

- Understand they will still need to pay rent at the end of the moratorium (October 3, 2021); and

- Understand that any false/misleading statements may result in criminal and civil actions. [6]

Crucially, landlords were not required to notify renters of the order’s protections, and many renters never understood the steps they needed to take to claim protection from evictions. Additionally, while landlords were prohibited in certain situations from completing an eviction (i.e., actually having a tenant removed forcibly from the property by local law enforcement), they were not necessarily prohibited from filing an eviction against the tenant in the court system, which can be as harmful as actually completing an eviction. Eviction filings show up on background checks and regularly hinder renters from procuring housing.

Backlash

Moratoria at the federal, state, and local levels have all received backlash, and many local judges simply ignored the federal order. For example, Ohio officials publicly announced that they would defy the CDC’s moratorium and continue eviction proceedings [7]. In some counties, it came down to individual judges to make decisions about how strictly to enforce the orders. For example, Nick Chu, Justice of the Peace for Precinct 5 in Travis County (Austin, TX), said, “Truly each judge has to look at the law and then also the arguments on both sides and apply those arguments.” [7] This variety of responses made it extremely difficult for renters to understand the extent to which they were protected from being evicted. Hyper-local differences abounded; the difference between a judge who dismissed an eviction filing and one who issued a writ of possession could be as small as the driving distance from one subdivision to another.

Unsurprisingly, both small, local landlords and large, corporate real estate investment trusts have protested the orders since they were initially announced. ‘Mom and Pop’ landlords, small landlords who own less than five rent-producing properties, have been hit the hardest. Many of them have been unable to meet their mortgage payments on the properties, and mortgage assistance for landlords has been limited, with funding prioritizing renters themselves. Benfer et al. reported that 58% of ‘Mom and Pop’ landlords have no access to emergency credit [1]. Evictions are financially difficult for landlords as well as for renters; many small landlords are unprepared for the court costs, short- or long-term vacancy, reletting costs, and the loss of 90-95% of rental arrears via sale to a debt collector or other third party that come as a result of evicting a renter [1]. If the property does not produce rental income (due to nonpayment or vacancy) for long enough, these small landlords may face bankruptcy or foreclosure, which could be financially devastating. There are broader consequences to the community as well. Foreclosure, in particular, can lead to lack of maintenance, urban blight, reduced property values for neighboring properties, and erosion of neighborhood safety and stability [1]. Additionally, the loss of property tax on the property impacts public service provisions such as city and state governments, schools, and infrastructure and managing or disposing of properties acquired through tax foreclosure [1].

Unsurprisingly, corporate landlords have also protested the measures across the country, culminating in a Supreme Court case. In August 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in Alabama Association of Realtors v. US Department of Health and Human Services that the CDC had overreached and that measures of this scale were out of its scope and mandate [8]. In the 5-4 decision, the Court wondered at the limits of the CDC’s authority: “Could the CDC, for example, mandate free grocery delivery to the homes of the sick or vulnerable? Require manufacturers to provide free computers to enable people to work from home? Order telecommunications companies to provide free high-speed Internet service to facilitate remote work?” [8]

Effectiveness

Research from the Eviction Lab out of Princeton University indicates that the moratoria profoundly impacted housing outcomes. In a typical year, the eviction filing rate, that is, the percentage of renter-occupied properties referred to eviction, is approximately eight percent [3]. Between September 4, 2020, and July 31, 2021, there was fewer than fifty percent of evictions than were expected, given historical trends [3]. In the jurisdictions reviewed in the data set, there were approximately 370,000 evictions filed, relative to the expected 700,000 filings [3]. Extrapolating its data from the thirty-one cities in the data set, the Eviction Lab estimates that combined federal, state, and local moratoria prevented almost 2.5 million evictions since early 2020 [3].

Multiple researchers concluded that the moratoria effectively limited the spread of COVID-19, particularly when strong local measures were in place. Researchers found that evictions lead to significant increases in infections, and eviction reduction policies were warranted and important components of COVID-19 control [9]. Further, Kathryn Leifheit, a postdoctoral fellow and epidemiologist at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, noted, “states that ended their moratoriums saw over 430,000 more cases [of COVID-19] and over 10,000 more deaths than they would have if they had maintained their moratoriums” [10]. Leifheit and her team found that lifting moratoria was associated with 1.6 times higher COVID-19 mortality after seven weeks and 5.4 times higher mortality after 16 weeks even when controlling for mask orders, stay at home orders, school closures, and testing rates, as well as characteristics of states and underlying time trends [11]. Despite the variety of restrictions and implementation guidelines, the moratoria successfully limited the spread of COVID-19.

Conclusion

While the federal, state, and local moratoria successfully delayed (not necessarily canceled) millions of evictions, the Eviction Lab acknowledged that such measures “did nothing to address underlying racial and gender disparities in eviction rates nor the concentration of eviction in hard-hit neighborhoods” [3]. Additionally, the orders did not forgive lost rent, and Congress has not instituted sufficient rental forgiveness programs. Despite the decrease in evictions over the past year and a half, a large proportion of renters remain at risk of being evicted in the near term and of falling victim to predatory practices in the longer term. Many underlying societal and legal conditions that lead to the regular eight percent eviction filing rate have not been addressed. For example, additional renter protections, such as the right to counsel, expungement of eviction records, and just-cause eviction standards, would all limit the number of evictions going forward [6]. While the eviction moratoria were an effective risk-mitigation measure to decrease the spread of COVID-19, they are not sufficient to address existing systemic issues.

Citations

1. Benfer, E., Vlahov, D., Long, M., Walker-Wells, E., Pottenger Jr., J.L., Gonsalves, G., & Keene, D.E. (2021, January 7). Eviction, Health Inequity, and the Spread of COVID-19: Housing Policy as a Primary Pandemic Mitigation Strategy. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7790520/pdf/11524_2020_Article_502.pdf

2. Benfer, E., Bloom Robinson, D., Butler, S., Edmonds, L., Gilman, S., Lucas McKay, K., Neumann, Z., Owens, L., Steinkamp, N., & Yentel, D. (2020, August 7). The COVID-19 Eviction Crisis: An Estimated 30-40 Million People in America are at Risk. National Low Income Housing Coalition. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/The_Eviction_Crisis_080720.pdf

3. Rangel, J., Haas, J., Lemmerman, E., Fish, J., & Hepburn, P. (2021, August 21). Preliminary Analysis: 11 months of the CDC Moratorium. The Eviction Lab. https://evictionlab.org/eleven-months-cdc/

4. Driessen, G.A., McCarty, M., Perl, L. (2021, October 21). Pandemic Relief: The Emergency Rental Assistance Program. Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46688#:~:text=In%20response%20to%20concerns%20about,116%2D260)

5. Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions To Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19 (2020, September 4). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/04/2020-19654/temporary-halt-in-residential-evictions-to-prevent-the-further-spread-of-covid-19

6. National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2021). Federal Mortarium on Evictions for Nonpayment of Rent. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/Overview-of-National-Eviction-Moratorium.pdf

7. Hernandez, K., ArguetaSoto, C. (2021, August 13). Local Judges Decide Fate of Many Renters Facing Eviction. Pew Trusts. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/08/13/local-judges-decide-fate-of-many-renters-facing-eviction

8. Alabama Association of Realtors, et al. v. Department of Health and Human Services, et al., 594 U. S. ____ (2021). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/20pdf/21a23_ap6c.pdf

9. Nande, A., Sheen, J., Walters, E.L. et al. The effect of eviction moratoria on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 12, 2274 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22521-5

10. Simmons-Duffin, S. (2021, October 21). Why helping people pay rent can fight the pandemic. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/10/21/1047291447/rent-help-can-slow-covid-spread

11. Leifheit, K.M., Linton, S.L., and Raifman, J., Schwartz, G., Benfer, E., Zimmerman, F.J., Pollack, C. (2020, November 30). Expiring Eviction Moratoriums and COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab196