Written by: James Warren

Edited by: Elisabeth Lembo

Background:

In October 2019, the Kincaid fire began. Spread and amplified by powerful winds, the fire ravaged northern California, burning over 75,000 acres of land and destroying hundreds of homes and buildings.[1] During the fire, Pacific Gas & Electric shut off power for over two million California residents to prevent downed power lines from causing new fires, potentially imperiling those who needed power for updates about the movements of the fires and necessary evacuations.[2]This situation, coupled with the Los-Angeles-proximate Tick Fire, led California Governor Gavin Newsom to declare a state of emergency in Los Angeles and Sonoma counties, resulting in the evacuation of 50,000 Los Angeles residents.[3]

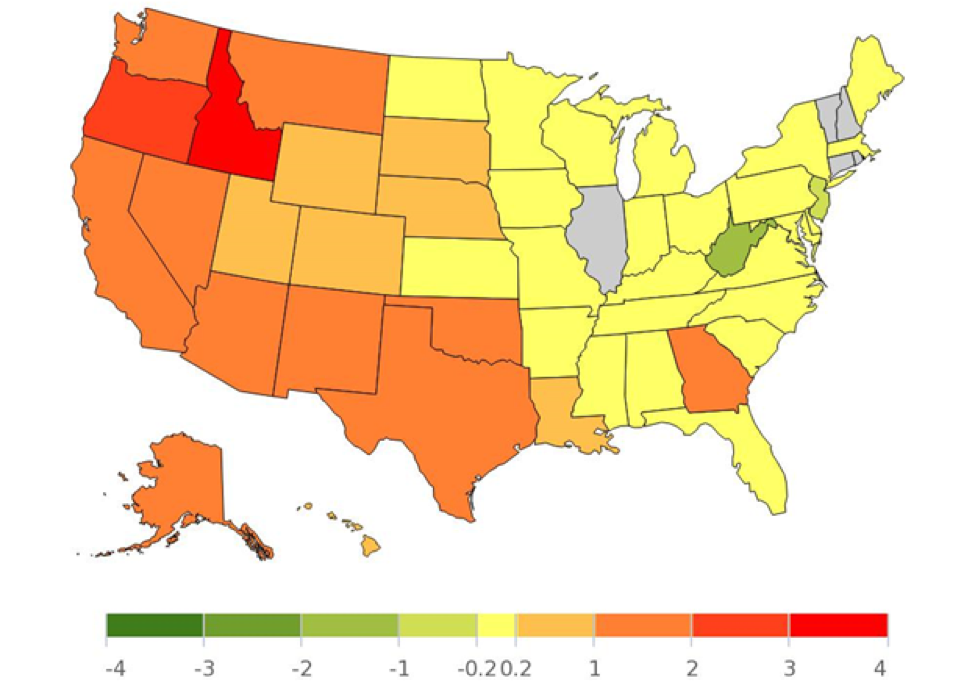

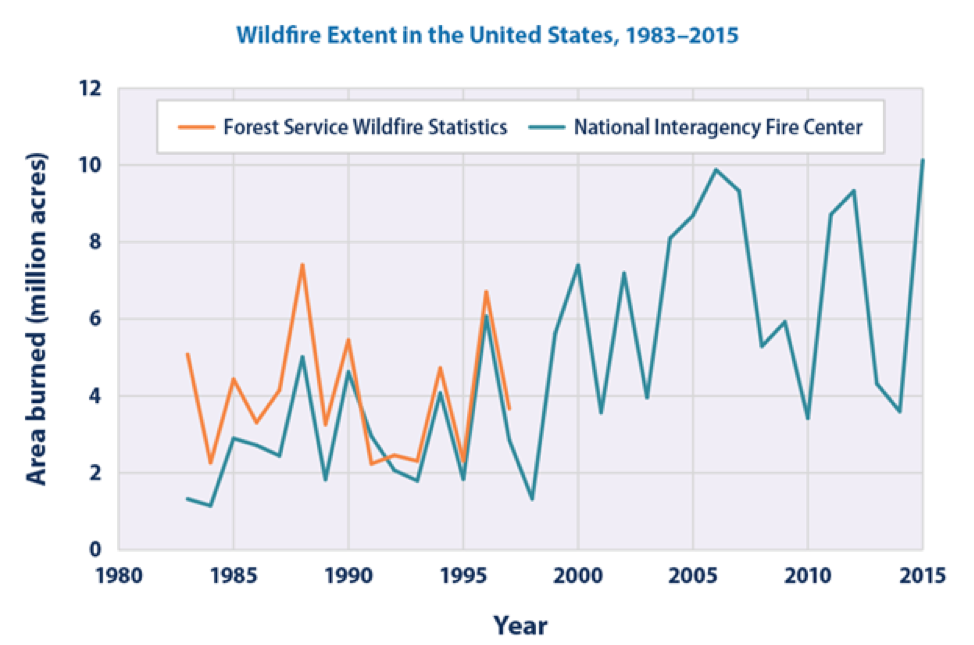

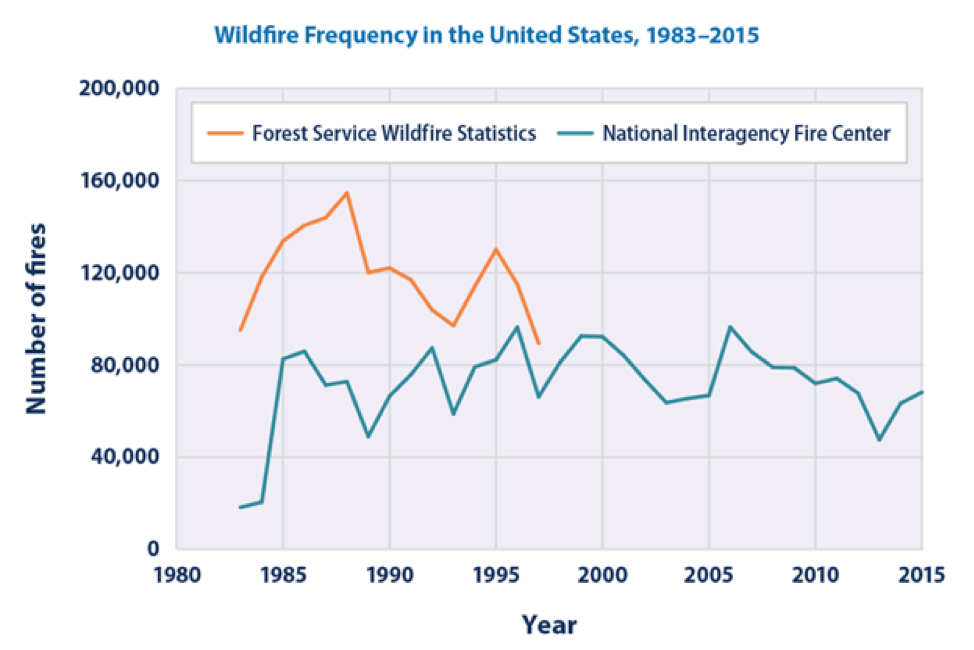

Forest fires like those ravaging California are becoming increasingly common nationwide. Almost every state has seen an increase in total acreage burned over the past thirty years (Figure 1).[4] Though 2019 has been a relatively quiet year, the trend toward more severe fires is clear. In 2018, for example, California suffered over 1,800,000 of acres of wildfire damage, with over 8.5 million acres burned across the United States as a whole.[5]Over the past thirty years, total acreage loss due to wildfires has been increasing dramatically, nearly doubling loss levels from the 1980s and 1990s (Figure 2).[6]In the same time frame, the total number of individual fires stayed relatively stagnant, meaning the fires are becoming more disastrous (Figure 3).[7]These dramatic increases have occurred despite technological improvements in fire suppression and increases in firefighting personnel.[8] Environmental causes–climate change and an extended drought season–explain the increase in fire size and intensity. But there are “unnatural” causes too: the mismanagement of U.S. Forest Service dollars.[9]The Forest Service’s mission statement is, “To sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations,” and all Forest Service resources and activities are guided by this central mission[10]As fires have increased in intensity and, concomitantly, in the damage they cause, the U.S. Forest Service has needed to shift its funds toward fire suppression activities.

Positive Feedback Loops and Budget Mismanagement:

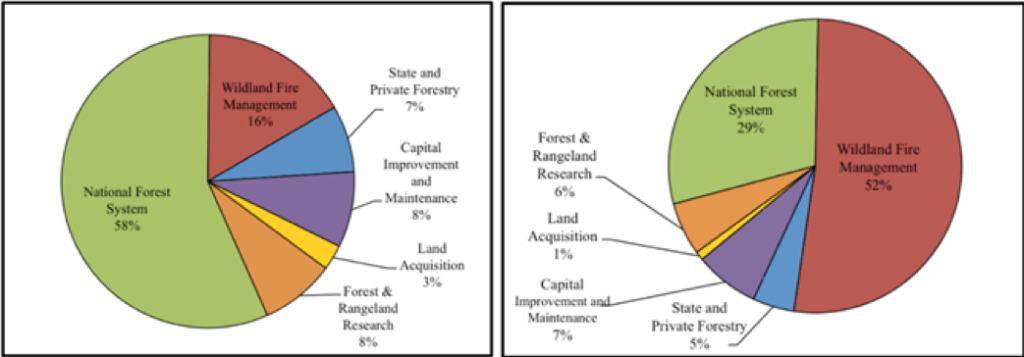

Because the wildland fire suppression budget is based on a ten-year rolling average, a number that misrepresents the needs of an individual year in the Forest Service, increasingly intense fire seasons leave the Forest Service fiscally unprepared.[11]This retrospective budgetary average is unique to wildfire response; as former United States Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack stated, “No other natural disasters are funded this way.”[12]Increased fire suppression measures have been necessary for the preservation of national forests and for the safety of those who live near them, but each Forest Service budget dollar allocated to suppression is a dollar taken from non-fire suppression programs (Figure 4).[13]Some of these programs include the very fire prevention measures necessary to mitigate the most catastrophic fires.[14] Diverting funds from fire prevention to fire suppression is a positive feedback loop, or a cycle where cause and effect flow into each other in an amplifying manner. That is, decreasing fire prevention efforts lead to more fires and an increased need for fire suppression. This feedback loop has plagued the Forest Service and its ability to manage forest health for years. While some steps to fix the budget have been taken, including a 2018 Executive Order restructuring the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Department of the Interior (DOI) to improve efficiency, these initiatives have fallen short of meeting the pressing needs of the United States’ forests.[15]

The “Fire Fix”:

In response to these mounting issues, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue successfully urged Congress for standalone funds dedicated to fire suppression to be added to the 2018 omnibus appropriations bill.[16]This “fire fix” is a joint budget authority (congressionally approved funds an agency may spend) for the USDA and Department of the Interior starting at $2.25 billion in 2020 and increasing by $100 million every year over the next 7 years. [17]According to the USDA budget summary, “the budget stability enabled by the additional budget authority will be leveraged by the agency to more strategically approach programmatic and fiscal management of wildland fire management programs.”[18]This budget authority enables the Forest Service to adequately provide fire suppression services without dipping into funds needed for fire prevention, protection of endangered species, forest restoration, and water management. By making room in the budget for fire prevention, the bill reduces the need for expensive emergency allowances in the long-run. This fix has been praised by Forest Service leadership as a positive step toward a healthy budget and sustainable planning for forest health.[19]

Conclusion:

While the new budget is imperfect – it includes budget cuts for certain Forest Service programs and eliminates others some see as important to rural economies and forest stewardship – it nonetheless represents an important initial step toward protecting forests and communities from the threat of uncontrolled wildfires.[20]According to the USDA 2020 Budget Justification, “this additional budget authority enables the agency to expand its focus beyond just current-year operations towards the long-term modernization of the wildland firefighting workforce and organization.”[21]In order to design policy that will sustain any long-term asset, such as the national forests and public lands of the United States, stability and long-term planning must be at the forefront of the policymaker’s mind. This imperative is becoming more crucial each year as the effects of climate change become more pronounced. By investing up-front in a specific budget authority for fire management, Congress fostered budget stability and enabled the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior to provide not only for the future health of forests, but also for the safety and sustainability of communities which rely on them.

References

[1]Amy Graff, “Kincade Fire Now 45 Percent Contained, Stays Steady at 76,825 Acres,” SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle, October 31, 2019), https://www.sfgate.com/california-wildfires/article/Kincade-Fire-Winds-are-calming-but-the-air-mass-14573853.php.

[2]Susie Cagle and Mario Koran, “’You Can’t Fight This’: California Wildfires Force Evacuation in Sonoma County,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, October 28, 2019), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/oct/27/california-wildfires-latest-thousands-evacuations-pge.

[3]Tim Arango and Thomas Fuller, “California Fires Update: Thousands Evacuated; Governor Declares State of Emergency,” The New York Times (The New York Times, October 25, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/25/us/santa-clarita-fire-sonoma-california.html)

[4]Environmental Protection Agency, “Climate Change Indicators: Wildfires,” EPA (Environmental Protection Agency, December 17, 2016), https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-wildfires).

[5]National Interagency Coordination Center, “Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report 2018,” NICC. 2018 (accessed November 24, 2019 https://www.predictiveservices.nifc.gov/intelligence/2018_statssumm/annual_report_2018.pdf) 1, 22.

[6]“Climate Change Indicators: Wildfires,” EPA (Environmental Protection Agency, December 17, 2016).

[7]Ibid.

[8]David E Calkin, Matthew P Thompson, and Mark A Finney, “Negative Consequences of Positive Feedbacks in US Wildfire Management,” Forest Ecosystems 2, no. 1 (2015), (accessed 22, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-015-0033-8).

[9]US Forest Service. “The Rising Cost of Wildfire Operations: Effects on the Forest Service’ Non-Fire Work” United States Department of Agriculture. August 4, 2015 (accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/2015-Fire-Budget-Report.pdf) 2.

[10]US Forest Service, “About the Agency,” United States Department of Agriculture, (accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.fs.fed.us/about-agency).

[11]US Forest Service. “The Rising Cost of Wildfire Operations: Effects on the Forest Service’ Non-Fire Work” United States Department of Agriculture. August 4, 2015 (accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/2015-Fire-Budget-Report.pdf) 3.

[12]Tom Vilsack, “The Cost of Fighting Wildfires Is Sapping Forest Service Budget,” US Forest Service, August 6, 2015, https://www.fs.fed.us/features/cost-fighting-wildfires-sapping-forest-service-budget)

[13]US Forest Service. “The Rising Cost of Wildfire Operations: Effects on the Forest Service’ Non-Fire Work” United States Department of Agriculture. August 4, 2015 (accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/2015-Fire-Budget-Report.pdf) 6.

[14]Ibid, 3.

[15]Exec. Order. No. 13855, 84 Fed. Reg. Presidential Documents (December 21, 2018), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-01-07/pdf/2019-00014.pdf) 45-48.

[16]United States Department of Agriculture. “Secretary Perdue Applauds Fire Funding Fix in Omnibus,” USDA, March 23, 2018, https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2018/03/23/secretary-perdue-applauds-fire-funding-fix-omnibus)

[17]United States Department of Agriculture. “FY 2020 Budget Summary,” USDA, (accessed November 22, 2019) 9.

[18]Ibid.

[19]Vicki Christiansen, “A Fire Budget for the 21st Century,” Leadership Corner (US Forest Service, March 30, 2018), (accessed November 22, 2019, https://www.fs.fed.us/inside-fs/leadership/fire-budget-21st-century).

[20]Whitney Forman-Cook, “State Foresters Hear Admin Request, Renew Emphasis on Long-Term Benefits of Healthier Forests,” National Association of State Foresters, March 19, 2019, (accessed November 22, 2019 https://www.stateforesters.org/newsroom/state-foresters-hear-admin-request-renew-emphasis-on-long-term-benefits-of-healthier-forests/)

[21]US Forest Service, “FY 2020 Budget Justification,” USDA (US Forest Service, March, 2019, (accessed November 24, 2019), page 108.

This message is approved

Yay I’m the first one to comment CONGRATS JAMES!!! 🤓

Lol