Closing the Opioid Treatment Gap: Effects of Eliminating the U.S. Waiver Requirement for Medication-Assisted Addiction Treatment Buprenorphine

By Trenton Ullrich, Contributing Writer, Public Health

Edited by Joseph Nolan, Associate Editor, Public Health

Graphic by Maralmaa Munkh-Achit

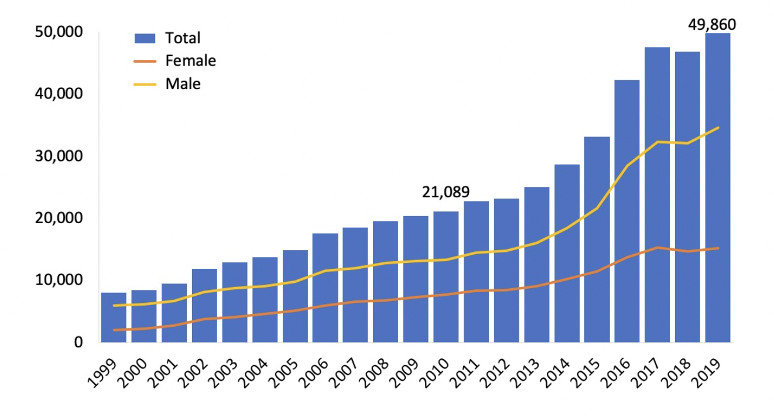

Fatal opioid overdoses took the lives of approximately 69,710 Americans (around 185 deaths per day) in 2020.[1] The year represented the continuation of a troubling trend spanning two decades, with more than 550,000 Americans losing their lives to an opioid overdose from 2000 to 2020.[2] The United States federal government sounded the alarm to this problem in 2017, declaring that the opioid epidemic was a public health emergency.[3] The problem only grew worse in the four years following that announcement, with yearly opioid-associated overdose deaths rising approximately 48%.[4]

Figure 1. National Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Any Opioid, Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse, Accessed on: 2/13/2021. (Although not represented on the chart, opioid overdose deaths spiked in 2020, with an estimated 69,710 deaths).[5]

Effective treatment options exist to help people suffering from opioid use disorder. In the United States, the problem for the first two decades of the twenty-first century has been connecting affected individuals to successful treatment options.[6] Opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment (“MAT”) is the most effective treatment for opioid use disorder. This treatment involves treating patients with one of three Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs that have increased treatment retention, reduced opioid use, and reduced mortality.[7] However, existing barriers prevent Americans suffering from opioid use disorder from obtaining MAT, with less than one in four addicts receiving one of the approved treatments.[8]

One potential barrier to obtaining MAT is the existing federal requirement that medical providers receive a waiver, commonly known as an “X-waiver,” from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine, one of the three approved medications to treat substance abuse disorders.[9] Prominent researchers,[10] lawmakers,[11] and medical groups[12] have called for abolishing the X-waiver requirement, citing it as a significant barrier to treatment. In 2021, a bipartisan group of legislators in both chambers of Congress introduced the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act of 2021, H.R.1384, legislation that, if passed, would eliminate the waiver requirement.[13] The bill is sponsored by Democratic Congressmembers Maggie Hassan and Paul Tonko, and Republican members Lisa Murkowski and Michael Turner.

Background:

The X-waiver, officially the DATA 2000 waiver, came into effect as part of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000.[14] This legislation was passed nearly unanimously in Congress, changing federal law to allow qualified practitioners to administer narcotic controlled substances in schedules III – V, like buprenorphine, for the purpose of narcotic addiction treatment outside of an opioid treatment practice. Under the law, practitioners who wish to prescribe buprenorphine for addiction treatment must obtain the waiver. Qualified practitioners were initially only physicians, but subsequent federal legislation since 2000 expanded who could apply for a DATA 2000 waiver to include some other medical professionals.[15]

For a brief time in early 2021, the U.S. government seemed on course to partially eliminate the X-waiver requirement. Before the end of President Donald Trump’s term in January of 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services announced that the federal government was changing existing guidelines to allow physicians to treat up to thirty patients at a time with buprenorphine without first obtaining a waiver.[16] The order did not apply to qualified practitioners other than physicians. However, shortly after taking office, President Biden’s administration reversed the Trump administration order, despite public support for eliminating the X-waiver requirement during Biden’s 2020 presidential campaign.[17] The Biden administration held that the President could not remove the requirement through executive action as Trump had attempted to do.[18] The stance of the Biden administration, as well as the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), is that only legislation passed in Congress can eliminate the waiver requirement.[19]

Policy Discussion:

Buprenorphine is one of two drugs considered to be the gold standard for the treatment of an opioid use disorder.[20] The use of the drug lowers the effects of opioid withdrawal symptoms and cravings to use opioids without having full opioid potency or effects. As a result, the treatment helps patients abstain from taking other opioids.[21] Previous studies supported by the U.S. federal government found that the treatment lowered rates of use, relapse, and mortality, with a 60% decrease in overdose deaths after a year in one study and another study showing that patients were twice as likely to be engaged in treatment after one month.[22] Further, qualified practitioners can prescribe buprenorphine in office-based settings,[23] and patients can take it at home.[24]

The success of buprenorphine treatment and other MAT options in the United States led the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to recommend that MAT options be available to every individual suffering from an opioid use disorder.[25] However, despite widespread acceptance of buprenorphine’s effectiveness in treating opioid use disorders, most Americans with an opioid addiction never receive the treatment.[26] A lack of providers eligible to prescribe buprenorphine, as well as limits the X-waiver places on practitioners who are eligible, prevents people in need of the treatment from receiving it.[27]

Patient limits on prescribers with an X-waiver are a barrier to buprenorphine treatment. Under existing federal guidelines, qualified practitioners with the waiver can only administer the treatment to 30 patients at a time during their first year with the waiver or 100 patients at a time during their first year if they complete specialized training. Providers who complete training can increase their limit to 275 patients at a time after one year.[28] Buprenorphine is the only prescribed medication in the country subject to such caps.[29]

As of November of 2021, there are just over 110,000 waivered providers across the United States. Most of these providers, 70.7%, are subject to the 30-patient limit, with 22.2% waivered for 100 patients and 7.1% waivered for 275 patients.[30] Providers, particularly those with a 30-patient limit, face the risk of hitting their patient cap under current provisions. Successful buprenorphine treatment can often last more than six months, meaning that once a prescriber takes on a new patient towards their limit, that patient will likely count towards their cap for the foreseeable future.[31] Eliminating the X-waiver would also lift the patient cap, allowing prescribers to treat as many patients as needed.

Existing waiver requirements are also a barrier to treatment because most physicians in the United States are not waivered. As of 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General found that 40% of counties in the United States do not have a single provider who can prescribe buprenorphine.[32] If the X-waiver were eliminated for physicians, the number of waivered U.S. providers would increase from about 110,000[33] to over one million.[34] In 1995, France took similar action, changing its laws to allow all registered medical doctors to prescribe buprenorphine without any special education or licensing. In the four years following this change, the country saw a 79% decrease in overdose deaths, and the number of individuals with an opioid use disorder receiving treatment increased more than 95%.[35]

Obtaining a DEA-X waiver in the United States can be a burdensome process that has the potential to discourage qualified providers from seeking the waiver. Any provider seeking a waiver to treat more than 30 patients at one time must complete 8 to 24 hours of training. Further, all providers seeking a waiver must file and submit applications with SAMHSA, a process that can take well over a month to obtain approval. Providers also are subjecting themselves to additional annual federal monitoring in some cases, as all practitioners approved to treat up to 275 patients must submit information about their practice yearly to SAMHSA for regulatory compliance monitoring.[36] The elimination of the waiver requirement removes the existing bureaucratic burden that comes with being a buprenorphine provider.

Potential Drawbacks:

The significant downside to eliminating the X-waiver is the uncertainty regarding the impact of such a move. Rather than removing a major barrier to treatment, evidence suggests that the waiver may not be what prevents most people with an opioid use disorder from receiving buprenorphine treatment.[37] Surveys of non-waivered providers have found that the waiver requirement is the least cited barrier to prescribing buprenorphine.[38]

More common barriers cited include inadequate training, lack of confidence in treating opioid use disorders, and insufficient reimbursement rates.[39] Further, stigma is a prevalent barrier.[40] A survey of primary care physicians reports that over three-quarters of respondents say they would be unwilling to work closely with a person with an opioid use disorder.[41] These barriers often apply to both waivered and non-waivered providers. Evidence suggests that obtaining the waiver is not enough to promote prescribing, as half of presently waivered clinicians do not prescribe at all. Moreover, waivered providers treat only 8 (median number) patients monthly.[42]

Conclusion:

The Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act of 2021, if passed, would eliminate the existing waiver requirement to prescribe buprenorphine to treat addiction in the United States. With bipartisan support for the measure in Congress, as well as support to eliminate the X-waiver from President Biden and former President Trump, the legislation has the real possibility of passing into law. As of January 2022, the legislation has been introduced in both chambers of Congress, and a bipartisan group of three Democrats and three Republicans have sent an open letter to President Biden encouraging its passage. While eliminating the X-waiver requirement will increase the number of eligible U.S. buprenorphine providers, it is unlikely the measure will be enough to meaningfully close the gap in treatment for people in need of MAT for opioid-use-disorder. Surveys of providers suggest that more common barriers cited as reasons not to prescribe buprenorphine must be addressed to see a consequential change in closing the gap.

References

- U.S. Center for Disease Control, “Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Up 30% in 2020,” September 7, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20210714.htm.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Overdose Death Rates,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, January 20, 2022, https://nida.nih.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- Robert A. Kleinman and Nathaniel P. Morris, “Federal Barriers to Addressing the Opioid Epidemic,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 35, no. 4 (April 1, 2020): 1304–6, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05721-5.

- U.S. Center for Disease Control, “Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Up 30% in 2020.”

- U.S. Center for Disease Control.

- Bertha K. Madras et al., “Improving Access to Evidence-Based Medical Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: Strategies to Address Key Barriers Within the Treatment System,” NAM Perspectives, April 27, 2020, https://doi.org/10.31478/202004b.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy, “Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder – NCBI Bookshelf” (National Academies Press (US), 2018), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534504/.

- SAMHSA, “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” 2019, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf.

- SAMHSA, “Become a Buprenorphine Waivered Practitioner,” 2022, https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner.

- Joseph Pergolizzi, Jo Ann K LeQuang, and Frank Breve, “The End of the X-Waiver: Not a Moment Too Soon!,” Cureus 13, no. 5 (n.d.): e15123, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.15123.

- Paul D. Tonko, “Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act Letter to President Joe Biden,” February 8, 2021, https://tonko.house.gov/uploadedfiles/matact.presidentbiden.02.08.21.pdf.

- Jeffrey A. Singer, “A Small but Certain Step Toward Removing the ‘X’ Waiver,” Cato Institute, January 16, 2021, https://www.cato.org/blog/small-certain-step-toward-removing-x-waiver.

- Margaret Wood Hassan, “S.445 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act of 2021,” legislation, February 25, 2021, 2021/2022, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/445.

- Tom Bliley, “Actions – H.R.2634 – 106th Congress (1999-2000): Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000,” legislation, July 27, 2000, 1999/2000, https://www.congress.gov/bill/106th-congress/house-bill/2634/all-actions.

- SAMHSA, “Become a Buprenorphine Waivered Practitioner.”

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), “HHS Expands Access to Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder,” Text, HHS.gov, January 14, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/01/14/hhs-expands-access-to-treatment-for-opioid-use-disorder.html.

- GW Regulatory Studies Center, “A Last-Minute Attempt to Partially X the X Waiver,” 2021, https://regulatorystudies.columbian.gwu.edu/last-minute-attempt-partially-x-x-waiver.

- Dan Diamond, “Biden Moving to Nix Trump Plan on Opioid-Treatment Prescriptions – The Washington Post,” 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/01/25/biden-buprenorphine-waiver/.

- SAMHSA, “FAQs About the New Buprenorphine Practice Guidelines,” accessed February 13, 2022, https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner/new-practice-guidelines-faqs.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives, ed. Michelle Mancher and Alan I. Leshner, The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health (Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2019), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538936/.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness, “Mental Health Medications | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness,” 2022, https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Treatments/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buprenorphine/Buprenorphine-Naloxone-(Suboxone).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy, “Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder – NCBI Bookshelf.”

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), “HHS Expands Access to Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder.”

- IT MATTTRs, “A Patient’s Guide to Starting Buprenorphine at Home” (IT MATTTRs, n.d.), https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/education-docs/unobserved-home-induction-patient-guide.pdf?sfvrsn=16224bc2_0.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives.

- SAMHSA, “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.”

- Kleinman and Morris, “Federal Barriers to Addressing the Opioid Epidemic.”

- SAMHSA, “Become a Buprenorphine Waivered Practitioner.”

- Mark Rosenberg, “Opinion | The X-Waiver Needs to Go,” July 26, 2021, https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/second-opinions/93753.

- SAMHSA, “Practitioner and Program Data,” accessed February 13, 2022, https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/practitioner-resources/DATA-program-data.

- Womens College Hospital, “Starting Buprenorphine Therapy A Guide for Patients” (Womens College Hospital, 2018), https://www.womenscollegehospital.ca/assets/pdf/MetaPhi/Buprenorphine%20book%2018.01.05.pdf.

- HHS Office of Inspector General, “Geographic Disparities Affect Access to Buprenorphine Services for Opioid Use Disorder OEI-12-17-00240 01-29-2020,” January 29, 2020, https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-12-17-00240.asp.

- SAMHSA, “Practitioner and Program Data.”

- KFF, “Professionally Active Physicians,” KFF (blog), February 7, 2022, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-active-physicians/.

- M. Fatseas and Marc Auriacombe, “Why Buprenorphine Is So Successful in Treating Opiate Addiction in France,” Current Psychiatry Reports, 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20201023084423/https://www.gacguidelines.ca/site/GAC_Guidelines/assets/pdf/131_Fatseas_2007.pdf.

- SAMHSA, “Become a Buprenorphine Waivered Practitioner.”

- Erin J. Stringfellow, Keith Humphreys, and Mohammad S. Jalali, “Removing The X-Waiver Is One Small Step Toward Increasing Treatment Of Opioid Use Disorder, But Great Leaps Are Needed | Health Affairs,” April 22, 2021, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20210419.311749/full/.

- Jeffrey R. DeFlavio et al., “Analysis of Barriers to Adoption of Buprenorphine Maintenance Therapy by Family Physicians,” Rural and Remote Health 15 (2015): 3019.

- Stringfellow, Humphreys, and Jalali, “Removing The X-Waiver Is One Small Step Toward Increasing Treatment Of Opioid Use Disorder, But Great Leaps Are Needed | Health Affairs.”

- Sarah E. Wakeman and Josiah D. Rich, “Barriers to Medications for Addiction Treatment: How Stigma Kills,” Substance Use & Misuse 53, no. 2 (January 28, 2018): 330–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1363238.

- Alene Kennedy-Hendricks et al., “Primary Care Physicians’ Perspectives on the Prescription Opioid Epidemic,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 165 (August 1, 2016): 61–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.010.

- Alexandra Duncan et al., “Monthly Patient Volumes of Buprenorphine-Waivered Clinicians in the US,” JAMA Network Open 3, no. 8 (August 24, 2020): e2014045, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14045.