Graphic by Maralmaa Munkh-Achit

Written by Julia Selby

Edited by Niamh Moore

The city-wide moratorium on evictions in Washington, DC began in March 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The goal of the moratorium was to keep people in their homes and out of the streets or communal living spaces as the pandemic spread across the country. As COVID-19 case numbers continued to rise in the city through the next year-and-a-half, legislation to extend the moratorium followed.

Though DC continues to face growing COVID-19 case counts throughout fall 2021, the city council ended the eviction moratorium on October 12, 2021, leaving many vulnerable renters teetering on the brink of homelessness. The end of the eviction moratorium threatens to cause an increase in homelessness throughout the city and higher levels of community transmission of COVID-19.

As evictions start up again in the city this fall, over 35,000 DC households reported they are currently behind on rent, and more than 27,000 households are not confident that they will be able to pay next month’s installment (U.S. Census Bureau 2021). Further, 12,500 households reported they feel they are very or somewhat likely to be evicted in the next two months. As a proportion of residents, more than 17% of DC is insecurely housed (U.S. Census Bureau 2021).

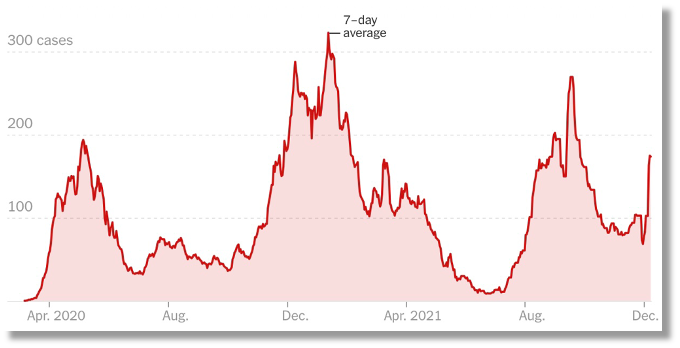

At the same time, COVID-19 case counts in DC remain at higher levels than last summer. As of publication, the most recent seven-day average for new cases in DC in December 2021 is 172 per day (New York Times 2021). Due to high community transmission, the city is at risk of further unmitigated spread.

Figure 1: 7-day average COVID-19 case counts in Washington, DC from April 2020 – December 2021 (New York Times 2021).

DC’s Eviction Moratoria and the Pandemic: March 2020 – February 2022

On March 17, 2020, the DC Council passed the first of several emergency legislative pieces in response to COVID-19. The bill created a 90-day eviction moratorium for residential tenants, meaning no new eviction cases could be brought before a judge, and the hearings for existing cases would be postponed (Council of the District of Columbia 2020). As the pandemic dragged on for a year-and-a-half, the council passed new bills and emergency orders to extend the moratorium incrementally. The most recent public emergency declaration was ordered by DC Mayor Muriel Bowser, on October 7, 2021. Crucially, however, this declaration did not extend the ban on evictions. The moratorium expired on October 12, 2021, allowing new eviction cases to be brought to court and leaving thousands of residents at risk.

Prior to October 12, the DC Council instituted a four-month phase-out of the moratorium to spread the number of eviction filings over a longer period of time. Through the end of 2021, landlords may file cases only for tenants who have not paid rent and owe more than $600. Starting January 2022, landlords may file eviction cases for any reason beyond non-payment issues. On February 1, 2022, hearings for all cases filed will be allowed, and by the end of February 2022 evictions for both payment and non-payment issues will be carried out (Schweitzer 2021).

As of publication, DC has suffered over 68,000 cases of COVID-19 and 1,199 deaths (District of Columbia 2021). Though the number of cases significantly decreased over the summer of 2021, the current state of the pandemic is more precarious. Community spread and variants of interest have increased case counts to levels seen at the pandemic’s start in the spring of 2020.

Because of the continued community impact of the pandemic, Mayor Bowser chose to extend the public health emergency declared in March of 2020. Though it was due to expire on October 8, 2021, the administration extended the declaration until January 7, 2022, citing new risks and recovery efforts that include “the economy, in-person education, and public safety” (Umana 2021). However, despite the ongoing risks, the public health emergency extension did not apply to the eviction ban.

Economic Effects of COVID-19 on DC Residents

The COVID-19 pandemic caused economic hardship and instability for thousands of DC residents. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, 195,000 DC households have been experiencing difficulty paying for usual household expenses during the pandemic (U.S. Census Bureau 2021). A national report by the U.S. Office of Human Services Policy found that the pandemic disparately harmed low-income households, especially people of color, women, and parents of young children. Further, it found that economic relief efforts at the state and federal levels may have been insufficient for many vulnerable households, including renters and families with undocumented immigrants (U.S. Office of Human Services Policy 2021).

While a rise in employment in the last several months has helped some households bounce back, the employment rate still stands below pre-pandemic levels (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 2021). Without further intervention to address economic uncertainty, households still experiencing financial hardship may not have the means to provide for basic necessities or keep up on rental costs. While the economic effects of the pandemic are still reverberating throughout DC, low-income households will continue to be vulnerable to eviction.

Evictions in DC and the Affordable Housing Crisis

Compounding the issue of housing insecurity due to the economic effects of the pandemic, DC is consistently ranked one of the most unaffordable metropolitan areas in the country (Lerner 2020; Jensen 2018; Burris 2021). In order to meet the need for housing, the DC metropolitan area would need to add 350,000 additional affordable units (Schweitzer 2018). For many renters facing a changing economic status or financial uncertainty, moving to a more affordable apartment within the DC area is simply not possible.

Because of housing inequity and the lack of affordable housing, DC’s renters experience eviction at a higher rate than the national average. One out of every nine renters in DC experience the eviction process (McCabe et al. 2020). The majority of evictions happen in predominantly black and low-income neighborhoods, highlighting the disproportionate impact on underrepresented groups.

Further, the same companies and individuals are known for filing the majority of eviction notices against tenants, with the same ten landlords filing 37% of all evictions in a given year (Gomez 2020). DC has one of the lowest eviction filing fees in the country, thus facilitating the ease and reducing the burden for landlords to evict tenants (McCabe et al. 2020).

DC’s eviction and unaffordability crisis existed before the COVID-19 pandemic. For residents already vulnerable to homelessness, however, the loss of jobs and economic uncertainty caused by the pandemic destroyed what little safety net previously existed.

Health Effects of Eviction During COVID-19

In addition to the financial concerns eviction brings, it also causes adverse health effects for families and individuals. Eviction or foreclosure increases the likelihood of “depression, anxiety, psychological distress, and suicide, and is detrimental to quality of life” (Vasquez-Vera et al. 2017, 202). Eviction can affect physical health as well. Various studies show associations between eviction and negative health outcomes, including “prevalence of poor self-reported health, chronic diseases, high blood pressure, domestic violence, and child maltreatment” (Vasquez-Vera et al. 2017).

In addition to mental and physical well-being, a rise in eviction rates may have public health effects for the community at large. An increase in evictions is predicted to increase COVID-19 infection rates and death (Benfer et al. 2021). When families and individuals are evicted, they are forced to live in communal living situations or with family or friends in larger households. Along with the economic hardship, evicted people also have limited access to healthcare. They may be less likely to comply with public health recommendations like social distancing, quarantining, or hand-washing, thus creating further risk for the spread of COVID-19 (Benfer et al. 2021).

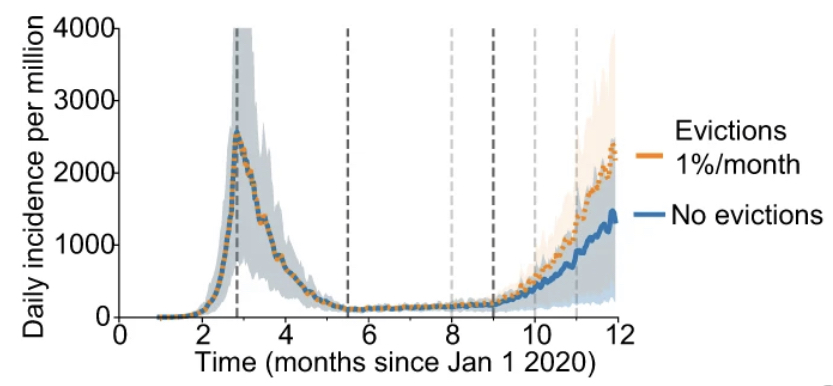

In a recent study, researchers found that transmission rates varied drastically under two model scenarios, one of a city with an eviction moratorium and one of a city without a moratorium. The model used previous infection data from several cities across the country, including neighboring Baltimore. Although infection rates decreased significantly in the summer regardless of eviction moratoria, case numbers increased drastically in the following months. The data displays a significant transmission difference depending on whether or not evictions had been halted (Nande et al. 2021).

Figure 2: Model of COVID-19 cases in a model metropolitan city, showing rates with evictions and without evictions.(Nande, et al. 2021).

As seen in Figure 2, the community spread of COVID-19 and the number of evictions are intertwined. From a public health perspective, community members are safer from COVID-19 if evictions do not occur.

How the City Can Respond

Extending the eviction moratorium until the end of the pandemic will help vulnerable DC residents, decrease COVID-19 transmission, and promote equity (Vasquez-Vera et al. 2017; Benfer et al. 2021).

Experts predict that evictions will lead to increased community spread of COVID-19 due to communal living, inability to social distance or quarantine, and lack of access to hygienic facilities. Compounding this, evictions lead to other negative health outcomes, including decreased mental health, increased stress on current health conditions, and an inability to access needed care. Therefore, to promote health for all residents and to remain consistent with the current public health emergency, DC must extend the eviction moratorium.

In addition, evictions and the COVID-19 pandemic pose racial justice issues. Black residents make up 77% of all COVID-19 deaths in the city (Ward 2021). Evictions disproportionately affect black families, particularly black women (Hepburn 2020). To promote a more equitable city, policy-makers must end evictions for the remainder of the pandemic.

References

Benfer, Emily A., et al. “Eviction, Health Inequity, and the Spread of COVID-19: Housing Policy as a Primary Pandemic Mitigation Strategy.” Journal of Urban Health, vol. 98, no. 1, Feb. 2021, pp. 1–12. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00502-1.

Burris, Rachel. “15 Most Expensive Cities In The US.” Quicken Loans, 9 June 2021, https://www.quickenloans.com/blog/15-most-expensive-cities-in-the-us.

“Council Unanimously Passes Emergency COVID-19 Response Bill.” Council of the District of Columbia, 17 Mar. 2020, https://dccouncil.us/council-unanimously-passes-emergency-covid-19-response-bill/.

“COVID-19 Surveillance.” District of Columbia. https://coronavirus.dc.gov/data. Accessed 26 Oct. 2021.

Gomez, Amanda Michelle. “These Landlords File the Most Evictions in D.C.” Washington City Paper, 30 Oct. 2020, http://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/500983/these-landlords-file-the-most-evictions-in-d-c/.

Hepburn, Peter, Louis, Renee, Desmond, Matthew. “Racial and Gender Disparities among Evicted Americans.” Eviction Lab, 16 Dec. 2020, https://evictionlab.org/demographics-of-eviction/.

Lerner, Michele. “Study: D.C. Is among the Least Affordable Places to Buy a Home.” Washington Post, 24 Sept. 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/09/24/study-dc-is-among-least-affordable-places-buy-home/.

Jensen, Jeremiah. “Here Are the Top 10 Most Expensive Rental Markets in the U.S.” HousingWire, 1 May 2018, https://www.housingwire.com/articles/43253-here-are-the-top-10-most-expensive-rental-markets-in-the-us/.

McCabe, Brian J., Rosen, Eva. “Eviction in Washington, DC: Racial and Geographic Disparities in Housing Instability.” Georgetown University, 2020, https://mccourt.georgetown.edu/news/eviction-process-impacts-1-out-of-every-9-renter-households-in-dc-mostly-in-black-and-low-income-communities-report-concludes/.

Nande, Anjalika, et al. “The Effect of Eviction Moratoria on the Transmission of SARS-CoV-2.” Nature Communications, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2021, p. 2274. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22521-5.

Schweitzer, Ally. “D.C. Council Will Phase Out The City’s Eviction Moratorium.” National Public Radio, 14 July 2021, https://www.npr.org/local/305/2021/07/14/1015788269/d-c-council-will-phase-out-the-city-s-eviction-moratorium.

Schweitzer, Ally. “Why There Isn’t More Affordable Housing In The D.C. Area.” WAMU, 24 Oct. 2018, https://wamu.org/story/18/10/24/isnt-affordable-housing-d-c-area/.

“The Impact of the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Recession on Families with Low Incomes.” U.S. Office of Human Services Policy, Sept. 2021. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/low-income-covid-19-impacts.pdf.

“Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 10 Nov. 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-economys-effects-on-food-housing-and.

U.S. Census Bureau (2021). Likelihood of Having to Leave this House in Next Two Months Due to Eviction. Retrieved from https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/hhp/2021/wk38/housing3b_week38.xlsx.

Umana, Jose. “Mayor Extends DC’s COVID-19 Public Emergency to 2022.” WTOP, 7 Oct. 2021, https://wtop.com/dc/2021/10/mayor-extends-dcs-covid-19-public-emergency-to-2022/.

Vásquez-Vera, Hugo, et al. “The Threat of Home Eviction and Its Effects on Health through the Equity Lens: A Systematic Review.” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 175, Feb. 2017, pp. 199–208. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.010.

Ward, Derrick. “Church Health Fair Tackles Alarming Disparities in COVID-19 Death Statistics.” NBC4 Washington, 23 Oct. 2021, https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/coronavirus/local-impact/church-health-fair-tackles-alarming-disparities-in-covid-19-death-statistics/2848511/.

“Washington, D.C. Covid Case and Risk Tracker.” The New York Times, 27 Jan. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/washington-district-of-columbia-covid-cases.html.