Abstract:

This article briefly demonstrates a systems thinking approach to help readers gain a more insightful understanding of differing perspectives Americans hold about placing the words “In God We Trust” on police vehicles. By using systems thinking tools such as MetaMaps to visualize relevant distinctions, systems, relationships and perspectives, the author challenges the way we communicate our differing understandings (mental models) by challenging how we think about our own thinking and the thinking of others. This article aims to give readers ways to determine how communicating different understandings can help others reach resolutions more clearly and efficiently.

Introduction

Four words, “In God We Trust,” have been appearing on the back of police cars throughout the country, sparking myriad debates about the use of these words on police vehicles and on other government property.

Although most Americans are aware that these four words make up our nation’s motto, social media provides people with a unique opportunity to voice their opinions about its interpretation and where it belongs. Facebook, most millennials’ source for news concerning government and politics, is not only a convenient way to rapidly uncover happenings from all over the world, but also allows its users to share their opinions within their network as stories appear. The many different opinions displayed for social consumption allow users to contribute to the discussion themselves. Online, as elsewhere, disagreement cannot be avoided—in fact, it is often encouraged during high-level decision making and in pedagogical environments. But when disagreements take a turn for the worse and people lose trust in information that opposes their viewpoint, conversations may end before new information is unveiled that could have possibly led to more favorable outcomes, such as less distrust and a greater willingness to accept other possibilities outside of one’s initial viewpoint. We often witness a news story that seems to provoke a heated disagreement and even leads to friends “defriending” one another.

In 2015, several news stories featured police forces putting “In God We Trust” on the back of police vehicles. A police department in Childress, Texas, publicly announced their new patrol car decals on Facebook, then deleted comments expressing dissenting opinions about the decals, including one that allegedly just read “bad move.” As feelings over these four words grew more oppositional, my curiosity grew as to why people were so upset about how others felt about the issue.

A Systems Thinking Approach

Derek and Laura Cabrera argue that “systems thinking must fundamentally balance what we know about the real-world systems and what we know about the knower.” Systems thinking is a methodology that examines the root of a problem by uncovering the relationship between systems—“the basic unit of how the natural world works”—while thinking deeply about “the way we construct mental models of this world.”

Using systems thinking as a lens to view the ongoing partisan discourse shifted how I saw not just my personal take on the issue, but also why I was thinking that way; this lens also revealed how my change in perspective was changing the problem itself.

The basic principles of systems thinking taught me that there was a lot of “unlearning” I had to do. First, I needed to stop looking at the disagreement and controversy over “In God We Trust” as complicated. Complicated means that certain formulae are critical and necessary to achieve a successful outcome. Rather, this controversy is best described as complex, meaning that it is made up of many interconnected elements with the capacity to change and evolve. Furthermore, thinking of the entire phenomenon of people responding argumentatively on Facebook as a complex adaptive system (CAS) provides insight into the issue. In particular, greater understanding comes from learning how parts of the system are connected with one another, possibly revealing how parts can be influenced.

Once I started to view the growing controversy through social media of “In God We Trust” on the back of police cars as a CAS, I was able to organize what I recognized based on my own mental models of the situation’s complexity.

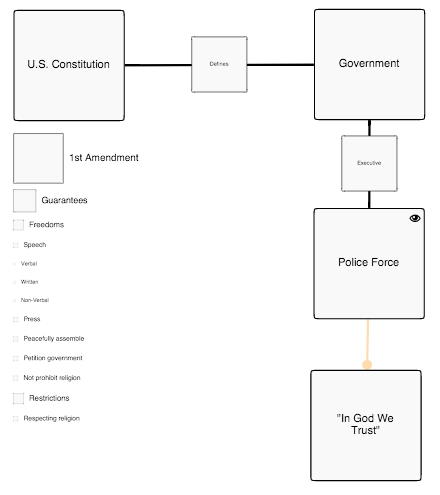

Figure 1. MetaMaps helps users visualize and map out their thinking according to the rules of DSRP (distinctions, systems, relationships, and perspectives).

First, I connected the Childress Police Force (representing one of several throughout the country) to the government and labeled their relationship as “executive” because the police force, as an entity, has an executive relationship with government. I then connected the government to the U.S. Constitution, because the Constitution defines the fundamental principles under which we are governed.

The First Amendment is at the forefront of the Bill of Rights under the U.S. Constitution. This amendment is often cited as both a granting authority for and protective force against having “In God We Trust” on the back of police vehicles. Opponents of displaying the saying on police cars may focus on the part of the law that reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” while proponents focus on the latter part, “or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Although opinions vary about whether police officers should, shouldn’t, or should sometimes display these words, my analysis focused on the two most polarized ways of thinking on this topic. In addition, this analysis is an effort to entertain the bivalent framework reflecting contemporary notions about what it means to hold “liberal” and “conservative” viewpoints.

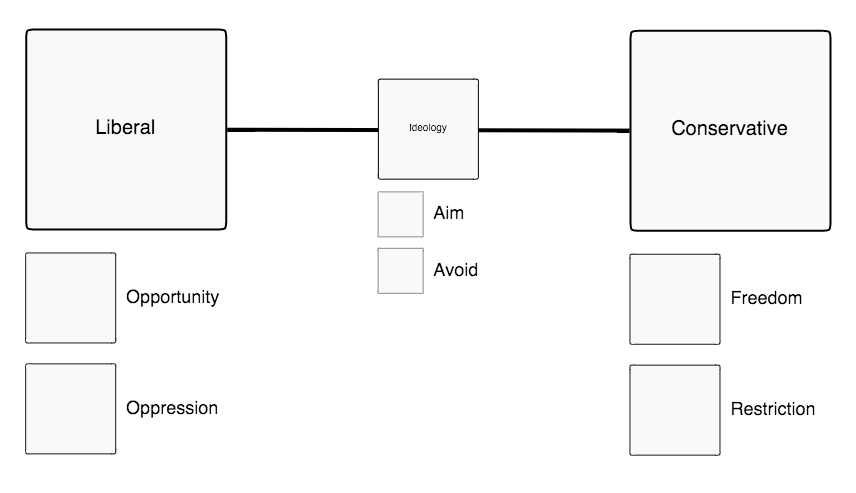

I wanted to look at the motives and platforms for each political identification. Therefore, I made two distinctions of what each group wanted to achieve and what each group wanted to avoid. Since the labels “liberal” and “conservative” belong to the same category of political ideologies, I created a relationship-channel to help me relate the parts of these two systems.

Figure 2. Bivariate American political ideology.

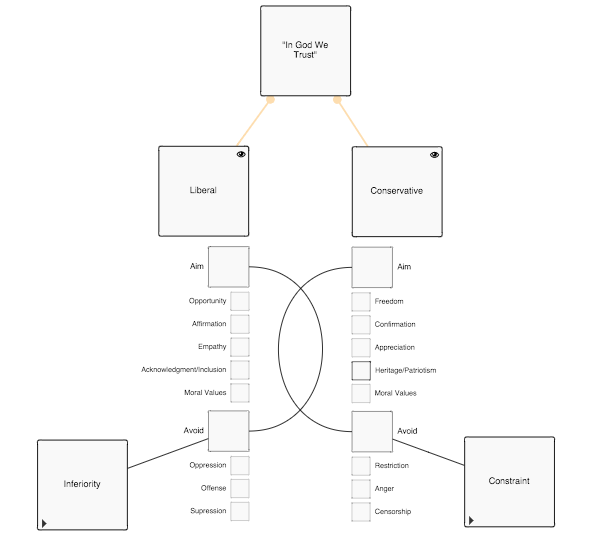

After positing the basic structure of these ideologies, I was able to articulate the fundamental desires of each group much more easily. By using systems thinking to organize these political ideologies, I was somewhat surprised to notice that many of the distinct relationships among what the groups were aiming for and avoiding were synonymous. Although these desires (opportunity, freedom) are separate distinctions within each group, they are also systems with other parts identified by perspectives. These perspectives are based on the public’s mental models from the relationships we ascribe to them. I kept realizing how much perspectives play an integral role in how things are ultimately shaped.

However, this raises the question: if two seemingly opposing groups have similar goals, why do both groups consistently seem so different from one another? Sometimes labels merely create barriers and lock us into our own perspectives. Is it also possible that conflicting groups think their values are more different than they actually are? While answers to these questions would take more analysis through systems thinking, it became more obvious that when we shift our perspectives, we transform distinctions and we therefore change what we’re looking at. Specifically, if you view my values as “close enough” to yours (whether consciously or subconsciously), maybe your thinking about me will shift and you will allow me the space to explain my thinking to you.

The Chief of Police from Childress, Texas, would not allow dissenting opinions on his Facebook post regarding the placing of decals on police vehicles. He even went as far as to post a letter on Facebook telling someone to “go fly a kite” in response to that person’s inquiry about removing the new decals. My hope is that the Chief of Police, along with all others, will give people the time and space to offer a dissenting opinion. Having different mental models is not necessarily a problem nor a cause for concern, but choosing to not understand why those differences exist can hinder our ability to gain a better understanding of a complex situation.

About the Author: Hill Wolfe ’16 is a fellow at the Cornell Institute for Public Affairs, pursuing a master’s degree in public administration concentrating in Government, Politics and Policy Studies. Hill serves as President of the Cornell Public Affairs Society and Communications Chair of Cornell University Women in Public Policy. Hill loves spending his free time volunteering, and has worked for a multitude of organizations dedicated to veterans’ issues, income inequality, gender equity, and at-risk youth and young adults. Hill received his Bachelor of Arts in both Media Communication and Public Administration from Northern Illinois University.

Leave a Reply