Abstract

There have been many historical iterations of the concept that the U.S. Congress behaves differently regarding foreign affairs than it does for domestic affairs. The first iteration of this was the two presidents thesis, which suggests that the president has increased latitude in foreign affairs and can consequently behave differently in that context than in domestic affairs.[1] In other words, as stated by Senator Arthur Vandenberg (D-MI) in 1947, politics stops at the water’s edge (or outside the continental U.S.) in terms of policies prioritized by the President and subsequently the Congress. One of the more prominent iterations of this thesis was the Cold War consensus, which described this same phenomenon, but explained it as solidarity against communism. This theory has not been adequately tested based on tangible data; this article tests the two presidents thesis by employing Mayhew’s significant legislation dataset,[2] which compares foreign bills to domestic bills. This test was done using OLS regression. A null result was found for the two presidents thesis, raising questions about many long-held beliefs about U.S. foreign affairs. Perhaps a one-sided presidents thesis would be more appropriate.

Background

Hundreds of pages have been written describing how presidential power in determining the congressional agenda is distinctly different dependent upon whether a given issue has reached the “water’s edge” or extended beyond it into foreign territory. Many scholars have pointed to the fact that Congress will lack strong electoral incentives to oppose the president on foreign policy issues. Other scholars have described informational asymmetries between Congress and the president regarding foreign affairs, explaining that with a lack of information on the facts of the situation Congress will follow the president. Regardless of mechanism, many scholars have started with the assumption that congressional-presidential affairs differ depending on whether a domestic or foreign issue is on the table. The problem with this assumption is just that—it is an assumption, and it is an assumption that must be true for the studies’ other mechanisms or methods to be at work. The objective of this paper is to test whether or not that assumption is supported by evidence. Are presidents more successful at getting legislation passed in Congress when issues of foreign affairs are considered as compared to domestic affairs? I hypothesize that presidents are in fact more successful with issues regarding foreign affairs. Many factors may influence the accuracy of this hypothesis, but I hypothesize the driving mechanism is electoral concerns. Since the American public writ large is often less concerned with foreign affairs, it seems unlikely foreign affairs would marshal the same electoral considerations from Congress as domestic issues do. Since these electoral motivations are weaker, it would be expected that Congress would provide less opposition to the president on foreign issues than on domestic issues.

To test of this question, the operational expectations and variables need to be defined. The key independent variable regarding the hypothesis is foreign affairs versus domestic affairs (as depicted via bills that regard foreign vs. domestic affairs), while the dependent variable is congressional-presidential relations determined via roll call vote coalition size, as detailed below. The expected outcome for the subsequent test will be that when comparing foreign affairs to domestic affairs, foreign affairs will produce closer alignments of congressional-presidential preferences than domestic affairs. Operationalizing variables that test this hypothesis will have to distinguish legislation type and will have to measure the relationship between Congress and the President. Foreign affairs legislation will be coded using a binary variable, with a one indicating that the legislation deals with issues relevant to foreign policy. Congressional-presidential relations will be measured using roll call vote coalition size. Roll call vote coalition size may be a rough measure of presidential support, but by using it to compare coalition size for both domestic and foreign issues, any differences should still reveal themselves based on the polarity of support. The empirical predication that extends from the significance of the roll call data is that the coefficient for foreign affairs will be positive and significant, indicating a distinct difference in coalition size based on whether legislation is foreign or domestic.

Data

As indicated above, the primary unit of analysis is roll call votes. These roll call votes have been obtained using the Mayhew significant legislation dataset. I will briefly explain here how the Mayhew two sweeps method, used for determining which bills are significant, was applied to establish the dataset.[3] Mayhew’s first sweep was done using legislative newspaper wrap-ups (newspapers from the bookend of each legislative session), which provided a gauge of significance at the time that the bill was passed. The second sweep was done by employing policy experts to retrospectively determine which they believed were the most important laws. Any additions that were not in sweep one were added to the dataset in sweep two.[4] Since Mayhew built this dataset, many scholars have employed it in a variety of approaches: its real value has been its ability to allow scholars to meaningfully sort minor laws from more major laws. The version of the Mayhew data used here is comprised of all significant laws from 1945-2004. It is important to only use these important laws instead of the whole corpus of passed laws because these are the laws that have determined the largest number of bills passed on domestic and foreign policy. It is much more meaningful, in considering the legislative implications of congressional-presidential dynamics, to compare these laws than to compare more minor laws that name post offices or bridges.

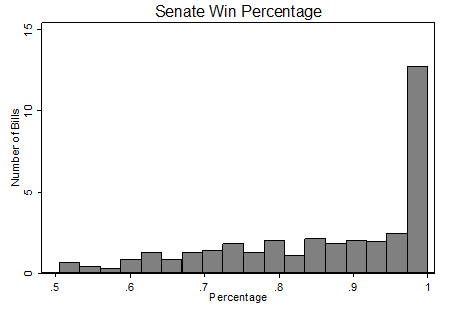

The dependent variable of interest in this dataset is Senate coalition percentage, calculated as the number of senators who voted “yes” on an piece of legislation divided by the total number of votes cast.[5] The Senate has been used to measure coalition size, rather than all of Congress, because the Senate has constitutional authority over treaty approval and is often considered the more foreign policy-focused of the two legislative bodies. Due to the Senate’s constitutional authority, there is a higher number of votes on issues of foreign policy in the Senate than in the House. In a way this is a weaker test than using total congressional percentage because of the Senate’s unique authority, but if there is not a relationship between coalition size in the Senate and foreign policy, there almost certainly will not be one in the House of Representatives. It should be noted that, while there have been a variety of analytical approaches to voice votes, they were coded as receiving complete support in this case because voice votes are only conducted when a substantial majority of members are expected to vote “yes.” This coding decision will be revisited in the results section, where the model is run with and without voice votes.

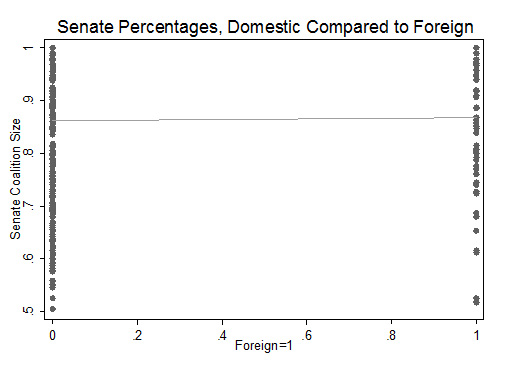

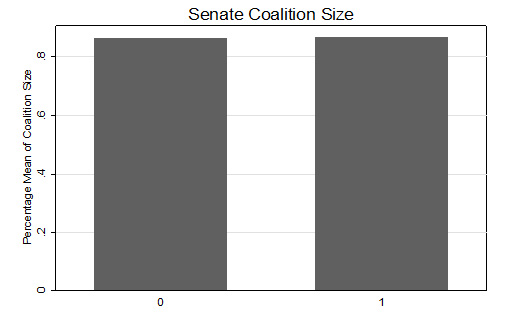

The primary independent variable of interest in this dataset is a dummy variable that indicates whether or not a given issue dealt with foreign policy. This variable was coded by examining the content of each piece of legislation and determining if it included any elements that would shape foreign policy. This included all treaties, military reorganizations, trade pacts, international resolutions, security pacts and national security resolutions. Many of these cases were clear-cut in their shaping of foreign policy, such as the NATO treaty; others were more fine-grained, such as Department of Defense Reorganization under Eisenhower. As with any project, some judgment calls had to be made: these were made with respect to the bill content and with no consideration (or even knowledge) of each bill’s respective coalition size. This dummy variable was created to allow for meaningful comparisons of issues that shaped foreign policy and issues that shaped domestic policy. The variable must be positive for the stated hypothesis to be supported. After compiling the data for the dependent variable and independent variable, a first look at the data was done by creating two graphics. The first graphic (see Table 1) is a scatter plot with a best-fit line that shows where the data is concentrated in this model and whether a relationship between the two variables may exist. Since the independent variable is binary, the scatter plot does not describe the data very well. Table 2, shown below, presents an alternative visualization: it is a bar graph comparing the two groups at their Senate coalition means. In both cases, foreign policy issues are equal to one.

Table 1

Table 2

Neither graphic represents a difference in coalition size between foreign and domestic issues. These graphics, however, constitute only a first impression, not a last step: they do not have any controls within them, and differences may exist after controlling for other variables.

The control variables in this model were obtained by merging a select set of variables from David Lewis’s political conditions dataset, which was constructed for the article “Testing Pendleton’s Premise: Do Political Appointees Make Worse Bureaucrats?”[6] Although these two subject areas do not agree with one another, some of the political conditions variables that Lewis uses are very compatible as controls in this model. Foremost, House and Senate DW-NOMINATE scores were included as control variables in this model. DW-NOMINATE scores measure preferences on a left-right dimension; they are a more nuanced approach to measuring preferences than party ideology. These scores are reasonable to include as a control because preferences should matter in determining the Senate coalition size as well as dictating foreign policy, with different preferences impacting the way in which members vote on a given issue. These preferences are especially important for the given time period, because southern Democrats had distinctly different preferences than did northern Democrats for many decades following WWII. House NOMINATE scores are included because the Senate may anticipate the preferences and actions of the HOUSE regarding issues that the House will have to vote on, and this anticipation may change the substance of the bill and thus the coalition size. This anticipation may be different for foreign versus domestic issues, since the preferences of House members, too, may be distinct on foreign policy as compared to domestic policy. Divided government is the next control from the Lewis dataset that is included in the model. Divided government is a dummy variable that has a value of 1 if more than one party shares control of the Senate, House and the presidency and a value of 0 if one party controls all three. A condition of divided government may impact coalition size since the two parties will have to convince opposing partisans to support specific legislation to get it passed. Divided government may also impact the outcome of votes on foreign policy versus domestic policy, as the two parties may have diverging foreign policy stances and would be forced to compromise. Total employment—the total number of individuals, in thousands, employed in the US workforce—is included as a control as well, serving as a small indicator of economic conditions. Economic conditions could skew coalition sizes for both domestic and foreign policy legislation: specific economic situations could create incentives for senators to vote in large numbers for economic aid or to change how they view (and vote on) foreign policy engagements. presidential administration in the dataset from 1945-2004 has been assigned a dummy variable as well. Each president has varying degrees of success within the Senate—some prove very good at rounding up votes, while others are less successful—and these abilities could alter the coalition sizes from administration to administration. Also, each president has a distinct foreign policy that could affect the foreign policy legislation that is put forth before the Senate. Finally, a war dummy variable is included in the model. This variable codes whether the US was involved in a major war during the year when the legislation was considered. Major wars may cause senators to attempt to show solidarity and thus vote in larger coalition sizes, especially for issues regarding foreign policy.[7]

One control variable that does not come from the Lewis dataset is a Cold War control. This control variable is a binary variable that has a value of one if the legislation was considered during the Cold War (1947-1991) and a zero otherwise. This variable is important to have in the dataset as numerous scholars have claimed some type of Cold War consensus. Theorizations of this consensus have ranged from asserting there were larger coalition sizes for all policy, in a show of solidarity against communism, to asserting solidarity specifically in foreign policy. If this mechanism is indeed at work, not including it as a control could skew the results of the model, because the consensus could explain an artificial inflation of coalition size regarding both domestic and foreign policy legislation, or only foreign policy legislation, during these years.

Methods

An ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used for this test. This OLS regression did not include any curvilinear terms or logged values, and the values remain untransformed. This simple model provides a better test than introducing complexity into the model. For the variables in this model, none of the variables of interest display any large disparities in range or would be easier to interpret if transformed. The only variable in this model for which a logarithmic transformation might make sense is total employment, but since that is a control variable, its interpretation is not of interest: the model was not built for and does not seek to explain its changes. (The lack of a transformation of that variable does not harm its ability to control: its interpretations are just not as intuitive.) Curvilinear terms are not included because there is no reason to believe that the relationship between Senate coalition size and the foreign policy variable is anything but linear, if there is a relationship at all. Theoretically, the coalition sizes should change at a constant rate since senators will have incentives to defect from or join a coalition at a constant rate. In addition, because the independent variable of interest here is a binary variable, squaring it would not have any effect, since its value would remain one or zero.

Interactions are not found in this simple model, either, because there is no reason to believe that the foreign policy variable is dependent upon another variable for its effect. The entire hypothesis is predicated on the idea that the president has dictated foreign policy to Congress, on average, and that Congress, on average, has supported at higher rates regarding foreign policy issues than regarding domestic issues. It is not a theory that is dependent upon other cases, but only dependent upon the institutional qualities of the president and Congress. These institutional advantages are what the model is testing and why coalition size is the dependent variable.

This simplified OLS regression model comes along with certain assumptions. The primary concern is regarding issues of endogeneity, when an explanatory variable is correlated with the error term, because endogeneity can impact the coefficients within an OLS model. One type of endogeneity problem occurs when a variable is omitted from the model and is correlated with the independent variable and the dependent variable. For this model, the vast array of controls, especially the presidential administration dummies, should help to address any omitted bias that could occur. These dummy variables attempt to capture other known explanations for what could impact coalition size. Reverse causality is the other major type of endogeneity problem that could bias the results of any regression. For this model, this would mean the model would suggest that Senate coalition size was determining whether or not an issue was foreign or domestic, instead of coalition size being affected by a switch from domestic- to foreign-focused legislation. Theoretically there is no reason to believe that coalition size determines what issue is taken up. The Senate sets an agenda and then votes on that agenda; the institutional norms of the Senate help to address any reverse causality concerns. The coalition size cannot be known until a vote on an issue is taken up, so it cannot determine the type of issue that is taken up.

Model fit is also a concern: it is predicated upon the assumption that the errors in the regression are normally distributed. The errors should be normally distributed; if they are not, another model may be a better fit. In this case the errors are relatively normal, with a slight positive skew, which is most likely the result of the small sample size and voice votes which are coded as being unanimous in the Senate. This slight skew could impact the size of the coefficients, but since it is not extreme, it should not impact the coefficients, as more data would likely produce results closer to a normal distribution. The model is also run with the exemption of the voice votes that account for some of the non-normal portions of the errors, and this should help to produce a model that is an even better fit for the data.

A few other lower priority assumptions, which must be considered because they can impact the size of the standard errors, are autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity, and multicollinearity. Autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity occur when errors are dependent upon previous errors in some way, or when they have larger variances at certain levels. Autocorrelation is not a concern here, as the errors are equally likely to be above and below the regression predication line: there is no systematic sorting of errors. Heteroscedasticity could be a possible concern, as there is some increase in the error variance when moving from domestic to foreign legislation, but this is largely a result of having less data for foreign issues than for domestic ones. It is not an issue of larger coalition sizes producing greater errors. Non-perfect multicollinearity could occur in this model, but it is not a major concern because, at worst, the standard errors could be too high. The standard errors being too high will just make the bar to reach significance that much higher, making the tests more conservative.

Some possible corrections to the model could be implemented in future research. Data could be extended through 2015 to help resolve some possible concerns with the error distributions. In addition, more variables could always be introduced if there is some omitted variable that a future researcher believes would be appropriate. Other corrections could be an instrumental variable approach, if a future researcher disagrees with the theoretical claim that reverse causality is not a concern, or an interaction correction, if a future scholar believes that presidential success on passing legislation regarding foreign policy only occurs in certain instances (such as during divided government). However, this simple model should provide an adequate test of the hypothesis that was put forth at the outset, with limited reasons for concern.

Results

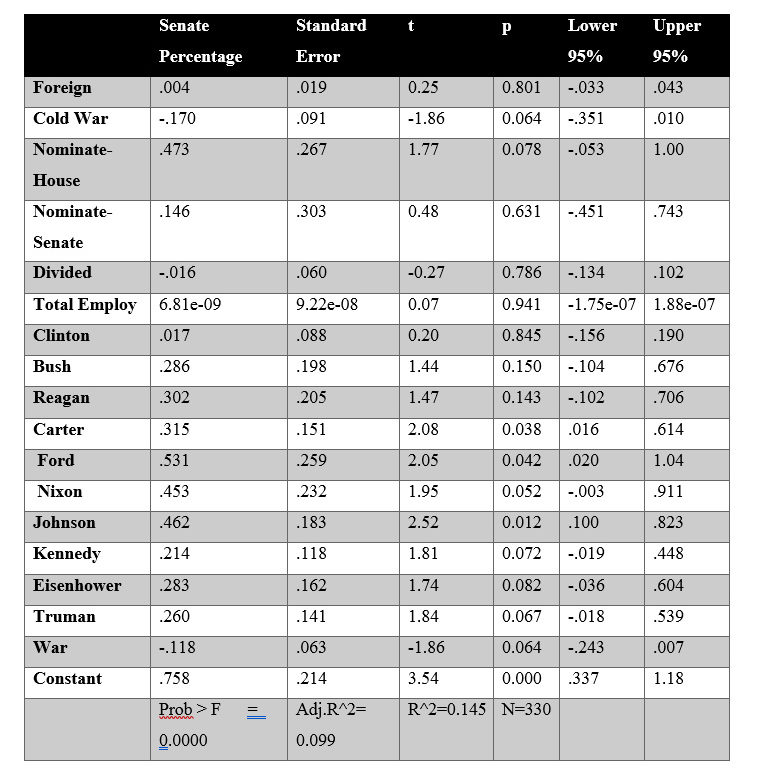

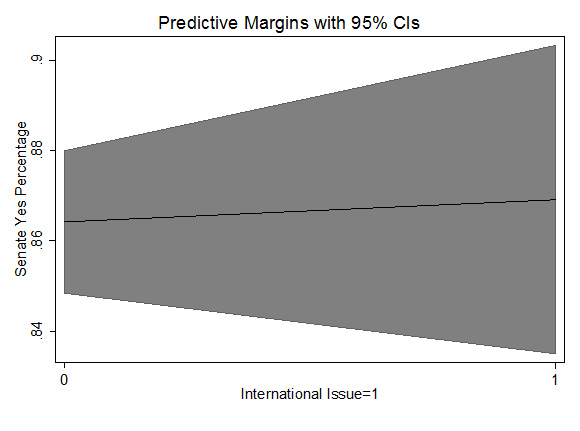

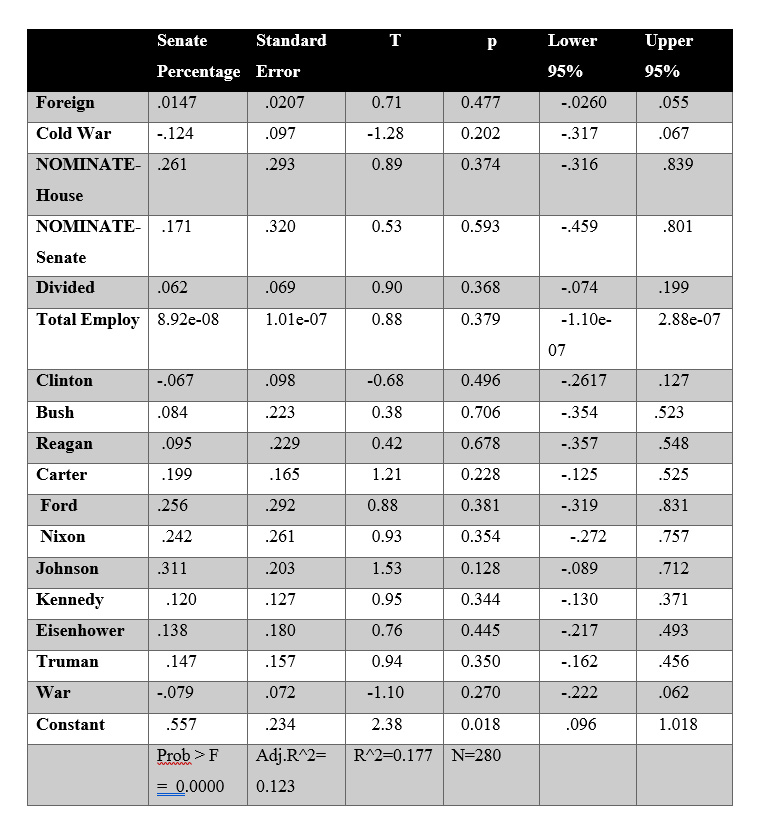

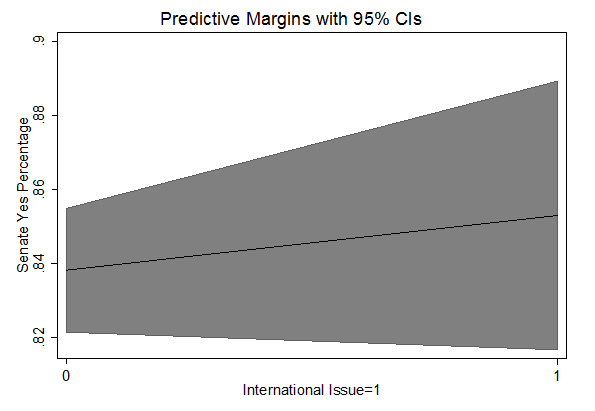

The full results of the regression can be found in Table 3 below. This table is provided in the spirit of full disclosure of the results. The foreign policy variable produced a very small coefficient of 0.004. This coefficient can be interpreted as suggesting that when comparing foreign legislation to domestic legislation—and controlling for House NOMINATE scores, Senate nominate scores, divided government, total employment, war, and all the presidential indicators—on average the Senate coalition size was 0.004 % higher. This result does not reach traditional levels of significance. This result does not support the hypothesis that Senate coalitions should be higher for international issues than for domestic issues. In this case, the two areas are not statistically distinguishable from each other, and the coefficient is extremely small. While a few of the presidential indicators reach traditional significance, it is not advised to interpret anything about those administrations from these results, as the model was not designed to test hypotheses about those variables. A more visual representation can be found below in Graph 1. Graph 1 is simply a graph of the marginal effect of the foreign policy variable with the 95 percent confidence interval shaded in. This graph highlights the extremely small slope, which shows that the effect is almost zero. The answer to the research question, based on these results, is that there is no difference between foreign and domestic issues in terms of Senate coalition size.

Table 3

Graph 1

When dealing with roll call data, there is always a question about how to code voice votes. As was noted in the data section, this model coded the voice votes as full support. This could be problematic, as it partially skews the data towards a larger coalition size (seen in Graph 2 below). This could bias the results in a detrimental way. To accommodate for this fact, the regression was run again with voice votes instead being coded as missing. The results of this regression can be found in Table 4. By coding the voice votes as missing, those observations were eliminated, because regression is run based on list-wise deletion. The interpretation of the foreign coefficient is the same as in the previous table. It can be interpreted as suggesting that when comparing foreign legislation to domestic legislation—and controlling for House NOMINATE scores, Senate NOMINATE scores, divided government, total employment, war, and all the presidential indicators—on average the Senate coalition was 0.014 % higher. This result does not reach traditional statistical significance either, and it does not support the hypothesis. The answer to the research question, even when excluding voice votes, is still that there is not a distinct difference in coalition percentage between domestic and foreign issues. An illustration of the marginal effect is shown in Graph 3: again, this illustration shows the 95 percent confidence interval around the line. This illustrates the lack of a distinction visually between the two as well.

Graph 2

Table 4

Graph 3

Discussion

The absence of significant results supports the idea that the two coalition sizes are not in fact different from each other. This lack of support for the concept of the two presidencies thesis provides evidence that politicization may occur at similar levels in Senate votes for foreign and domestic issues. It seems from these models that institutional informational differences or other factors do not lead to a president who is free to impose personal will in the foreign policy arena. Nor does there appear to be a Cold War consensus that leads the Senate to support foreign policy at higher rates than domestic policy.

The lack of significance does not make this modeling endeavor useless; it instead challenges common assumptions that may not be true. Because of the anemic findings in this paper, future models will not be able merely to assume that the president has more latitude in foreign policy, but will have to support the assumption in some meaningful way. Additionally, this test was a relatively easy test for the hypothesis because the Senate votes on a larger number of foreign policy issues, such as treaties. It would be expected that these results would be even weaker if Congress as a whole, or just the House of Representatives, were tested. If a relationship was not found in the Senate, it may not exist at all.

However, despite this lack of evidence, the two presidencies concept may exist in more informal ways. This test was done using roll call votes, a formal gauge of support. It could be hypothesized that this relationship is an informal one and cannot be meaningfully captured using roll call votes. However, the lack of evidence found in this paper does not bode well for a theory of differing behavior when comparing domestic versus foreign policy.

Conclusion

This paper sought a concrete test for whether or not the president garnered greater congressional support on foreign policy issues than on domestic issues. The results of this test did not support that finding, as the comparison coefficient was not statistically different from zero. These results question many commonly-held assumptions about presidential-congressional relations. These findings are important because they encourage future researchers to test commonly-held assumptions and think critically about why those assumptions may or may not be true. As a field, it is important that we do not reject research that produces null results: often null results have just as much to convey as significant results.

These results do not support the idea of two presidents, but rather one president who is just as constrained by Congress regarding domestic affairs as foreign affairs. Perhaps it is time to consider the idea that Congress is just as active in foreign affairs as in domestic affairs.

Future research should focus on why an electoral-obsessed body may still be able to constrain the president in foreign affairs. It should also focus on possible ways for Congress to overcome the president’s institutional advantages in foreign policy in order to act as an effective constraint—at least as effective as it has been in domestic affairs. Future research should focus on these patterns and why a null result may have been uncovered in this case. Maybe politics does not stop at the “water’s edge”: maybe it never stops.

References

- Wildavsky, Aaron. “The Two Presidencies,” Trans-Action/Society, 4 (1966): 7-14. ↑

- Mayhew, David Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946-2002, Second Edition. Yale University Press, 2005. ↑

- If more information is sought on the two sweep system, please refer to Mayhew (2004) ↑

- Mayhew, David Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946-2002, Second Edition. Yale University Press, 2005. ↑

- Mayhew, David Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946-2002, Second Edition. Yale University Press, 2005. ↑

- Lewis, David “Testing Pendleton’s Premise: Do Political Appointees Make Worse Bureaucrats?” Journal of Politics 69(4):1073-88 (2007). ↑

- Lewis, David “Testing Pendleton’s Premise: Do Political Appointees Make Worse Bureaucrats?” Journal of Politics 69(4):1073-88 (2007). ↑