Written By: Rafael Morales Guzman

Edited By: Eghosa Asemota

In March 2018, the Mexican Congress approved a new regulatory framework for the Financial System known as the Financial Technology Law (FinTech Law). The FinTech Law is based on five fundamental principles, one of which is financial inclusion. According to the World Bank, financial inclusion refers to the idea that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services – transactions, payments, savings, credit, and insurance – that meet their needs and are delivered in a responsible and sustainable way.[1] Financial inclusion continues to be a recurrent theme on Mexico’s agenda. Over the last decade, the government has been promoting policies to boost the level of financial inclusion in the country but to no avail. Financial Technology (FinTech) appears to be a promissory alternative to achieve these goals as it has the potential to transform the way that financial services are delivered and designed.[2] The expected outcomes of the Law are not only an increase in financial inclusion but also the promotion of competition and innovation within Mexico’s financial system, contributing to the development of this nascent industry.

While the purported benefits of the Law are well stated, there are still many uncertainties regarding its implementation and its effects. For example, if FinTech startups face an excessive regulatory burden, there is a risk of inhibiting innovation in the financial market and missing the financial inclusion target. Moreover, FinTech cannot be considered the ultimate means of reducing barriers to access and use of financial instruments; rather, it should involve an integral strategy where diverse stakeholders from government agencies, the private sector, and NGOs are involved in support access to, use of, and education about the financial services.

Government Policies for Financial Inclusion

Over the past ten years, the Mexican government has tried different policies to actively promote financial inclusion through different mechanisms. Past policies have included the creation of basic banking accounts, the application of the mobile banking and niche banks, and the bank correspondence service– none of which have been enough to increase observed levels of financial inclusion in the country.

From 2002 to 2008, the government promoted the creation of cooperative savings and credit institutions. In 2009, the government also mandated the use of financial accounts to transfer government subsidies to promote the use of banking services by the beneficiaries of social programs and those who receive the payment via payroll. At the end of 2008, a change in the regulation allowed financial intermediaries to implement a corresponding system. This policy enabled the intermediaries to provide basic financial services through third-party non-financial commercial businesses such as retail or convenience stores, pharmacies, and supermarkets. The type of services that correspondents could offer includes deposits to bank accounts, loan payments, utility payments, cash withdrawals, check collection, and opening savings accounts.

At the beginning of 2011, the government tried to operationalize and coordinate efforts from public and private institutions to disperse services. With this objective, the Mexican government established the National Council for Financial Inclusion (CONAIF for its acronym in Spanish), which is the advising and coordinating institution through which financial authorities coordinate, implement, and monitor the National Policy for Financial Inclusion.[3] The policy guides the actions of CONAIF’s members regarding all financial inclusion matters, the efforts of interested stakeholders —such as public and private financial entities and non-governmental organizations— and acts as a coordination tool among authorities of the financial system to determine priorities. Among the three main pillars of the National Policy for Financial Inclusion, the second pillar, “Use of Technological Innovations for Financial Inclusion,” focuses on the ways that technological innovations can expand the use of financial products and services. The passage of the FinTech Law in March 2018 embodied this second pillar.

Examining Financial Inclusion and Financial Access in Mexico

Despite these policies, financial inclusion levels in Mexico continue to be embryonic. Current incipient levels of financial inclusion do not correspond to the Mexican economy. According to the Financial Access Survey conducted by the International Monetary Fund in 2011,[4] Mexico presents one of the lowest levels of financial access in Latin America with six bank branches per every 1,000 inhabitants and a banking loan portfolio that is barely twenty percent of the country’s GDP (USD $1.21 trillion as of 2018).[5] According to a 2012 study conducted by the World Economic Forum to assess the financial development conditions in sixty-two countries, Mexico ranks fifty-first in the market penetration of bank accounts and thirty-first in commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults.[6] Recent data collected by the World Bank in 2017[7] reveals that while seventy percent of the world’s population has an account in a formal financial institution, only thirty-seven percent do in Mexico. Some experts like former Central Bank Governor, Guillermo Ortiz claim that this pattern of low financial inclusion levels is a consequence of the financial crisis of 1995.[8] Following the crisis, main suppliers of financial services have restricted their operations to only a few sectors of the economy. Consequently, the Mexican banking system is highly concentrated by a few banks that primarily provide credit to blue-chip firms, who have a better credit history than small borrowers. These banks are also characterized by the high cost associated with the provision of credit to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), or individuals without collateral or a credit history.

It is important to note the implications of having low levels of financial inclusion and barriers to accessing basic financial services. Several empirical studies show that access to basic financial services contributes to economic development, poverty reduction, income growth, stable consumption, and accelerated investment projects. [9] Access to credit also leads to an increase in consumer spending and therefore boosts the economy. Better financial access and better financial inclusion could, therefore, lead to economic growth, a higher GDP, and a more productive Mexico.

Innovation and Technology in the Financial Services Industry

The dynamism of digital, mobile, and information technology over recent years has enabled the emergence of new agents in the financial system collectively known as FinTech. According to the Financial Stability Board (FSB), FinTech is defined as “technologically-enabled innovation in financial services that could result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on the provision of financial services”.[10]

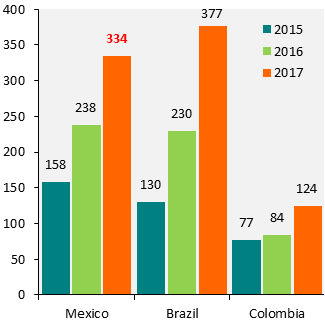

In Mexico, FinTech is a relatively nascent industry, but it has shown an active evolution. According to Finnovista, by the end of 2017, there were 334 FinTech companies in Mexico, a significant increase of forty percent with respect to the previous year and from 2016 to 2017 the industry grew more than fifty percent (Figure 1).[11] Some of the main drivers of this growth are the high use of internet and mobile technology in response to low banking access, concentrated consumer loan offering, and a robust entrepreneurship ecosystem. Such factors have contributed to the development of these new types of financial companies providing innovative technology-based services and products in different sectors of the economy.

Figure 1: FinTech Industry in Selected Latin American Countries (Number of FinTech Companies)

|

| Source: Finnovista FinTech Radar (2018)[12] |

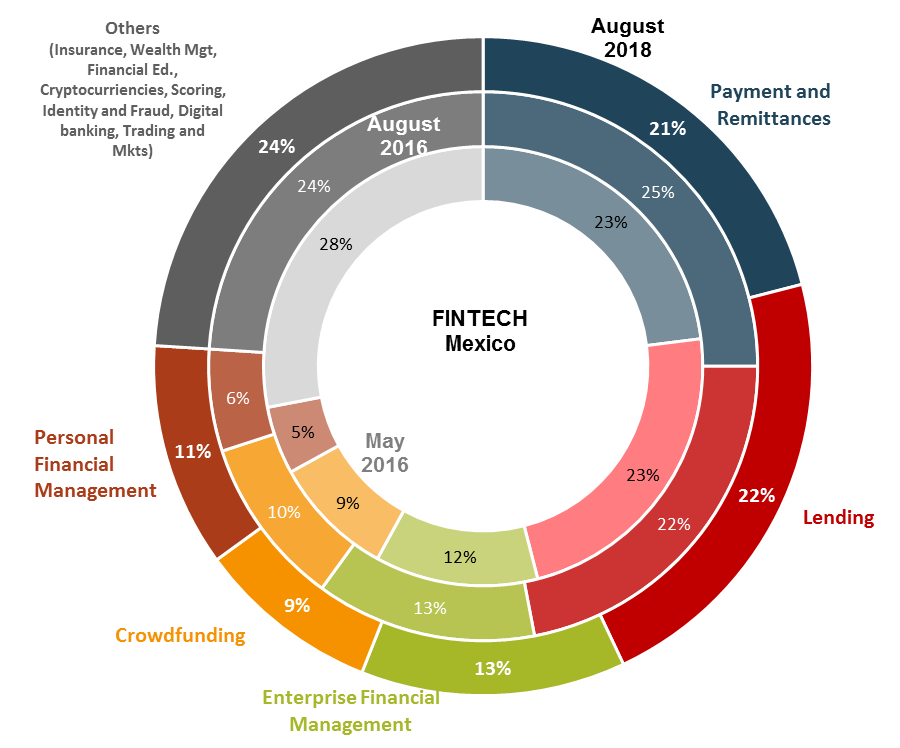

According to Finnovista, the eleven different segments in the FinTech realm where technological innovation is taking place are: a) Payments and Remittances; b) Lending; c) Enterprise Finance Management; d) Personal Finance Management; e) Crowdfunding; f) Wealth Management; g) Insurance; h) Financial Education and Saving; i) Scoring Solutions; j) Identity and Fraud; and k) Trading (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Evolution of Principal FinTech Sectors in Mexico, May 2016 to August 2018 (% of Companies in Each Sector) |

|

| Source: Finnovista Fintech Radars for Mexico[13] |

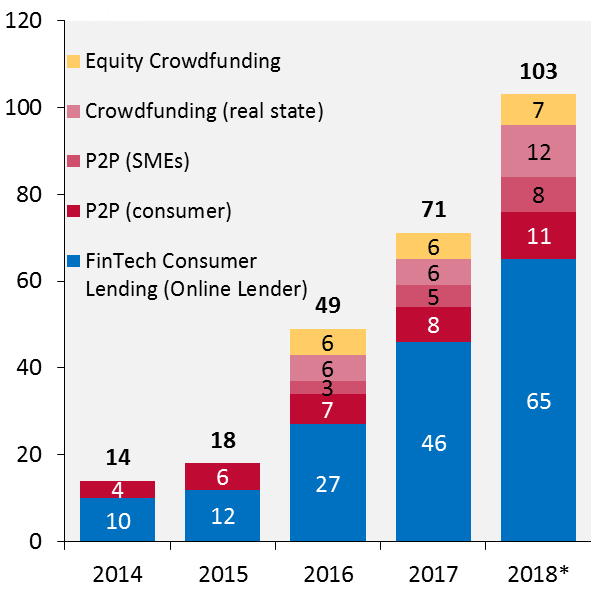

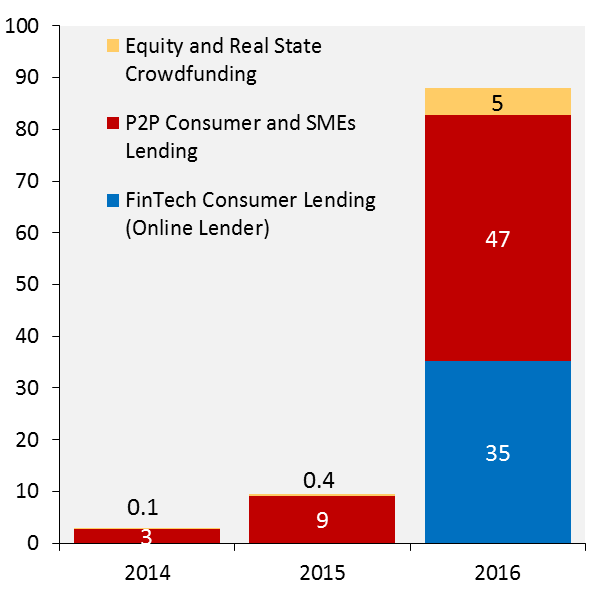

Among those sectors, the most vibrant have been lending and crowdfunding. According to the Financial Stability Board, FinTech Lending is a broad category that refers to credit activities provided by electronic platforms that facilitate a range of credit services, including secured and unsecured lending, and non-loan debt funding such as invoice financing. Such platforms are commonly referred to as “peer-to-peer (P2P) lenders” or “marketplace lenders.” Crowdfunding refers to the practice of funding a project or venture by raising monetary contributions from a large number of people. It is often performed via internet-mediated registries that facilitate the money collection for lending or equity.[14] Online platforms that carry out crowdfunding practices by matching borrowers directly with lenders are known as loan-based crowd funders. According to a study by the University of Cambridge in 2017,[15] the Fintech Lending sector in Mexico accounted for the highest total market volume in 2016 in Latin America ($114.2 million), which is driven mainly by crowdfunding and online lending with a growth of 601 percent, ($40.6 million in 2016). Together, these two segments made up fifty percent of Mexico’s total FinTech lending market as observed in the figures below.

Figure 3A: Mexico’s Lending and Crowdfunding Sectors (Number of Companies) |

Figure 3B: Mexico’s Lending and Crowdfunding Market Volume (in USD Million Dollars) |

|

|

| Source: Finnovista FinTech Radar (2018).[16] | Source: The Americas Alternative Finance Industry Report (2017).[17] |

In a country where small and medium micro-enterprises employ seventy percent of the labor force and represent fifty-two percent of the GDP, access to alternative funding channels is essential for the development and progress of the country. New FinTech companies could represent a viable alternative to finance those enterprises.

Rationalizing FinTech Regulation in Mexico

Although the emergence of financial technology is not exclusive to Mexico, the actions taken to regulate the sector were new. Though there is no international consensus about how the FinTech industry should be regulated, Mexico’s approach is distinct from most countries. Instead of recognizing the new FinTech companies under some existing statute, regulators decided to create a new tailored framework for those new companies.

The regulation of markets in the economy is underscored by concerns about efficiency losses. Typically, financial markets are among the most regulated due to their susceptibility to market failures like asymmetric information, moral hazard, and externalities associated with financial crises. According to Carletti and Vives, financial regulation has two main purposes: consumer protection and systemic risk prevention. [18] In the case of FinTech, the existence of market failures justify its regulation.

According to Robles-Perio, FinTech innovations like crowdfunding must be regulated due to the existence of serious information asymmetries generated by the anonymity of the internet’s usage. This anonymity could encourage fraudulent behaviors as there are financial resources involved in the transactions and money from retail investors are at stake.[19]

An additional reason to regulate the FinTech sector is to provide a fair arena for FinTech companies to compete with financial institutions while preventing the risks that new financial activities could ignite. For instance, people lending through FinTech companies are not fully aware of the implicated risks of such activities. Also, new methods of collecting data could generate concerns about data privacy and the misuse of personal data. Furthermore, difficulties in identifying customers, electronic fraud, and cyber-attacks are among some of the main vulnerabilities of FinTech companies.

Analyzing Mexico’s FinTech Law

Recognizing the dynamic nature of the industry, the Mexican FinTech Law was drafted in principle-based terms, leaving space for the development of secondary rules. Those principles include: i) financial inclusion; ii) consumer protection; iii) promotion of competition; iv) financial stability preservation; and v) the prevention of illicit activities (money laundering). Under the first principle, the main objective of the Law is to encourage innovation in the financial sector to increase the levels of financial inclusion by allowing the entrance of new competitors that have the capacity to provide low-cost technology-based solutions and introduce innovative financial products and services. In that regard, the Law was designed to offer useful mechanisms to segments of the population that are currently unattended to by traditional financial intermediaries.

The FinTech Law establishes a formal regulatory framework applicable to companies who provide financial services through information technology platforms and digital technology tools. The new Law gives certainty to industry participants, provides guarantees to the users, and allows FinTech companies to formally compete within the financial sector by providing rules about innovation in financial markets such as crowdfunding and cryptocurrencies. It also permits the sharing of data by financial institutions through public application programming interfaces. The Mexican FinTech Law regulates the following areas:

Financial Technology Institutions: The Law establishes the minimum requisites for the organization, operation, functioning, and authorization of institutions that offer financing, investment, savings, payments, or transfer activities through alternative means of access, such as internet, interfaces, or any other means of electronic or digital communications. These institutions are categorized depending on their main core business activities into crowdfunding institutions (companies that connect investors and solicitors of debt, equity, co-ownership, or royalties funding, through electronic or digital means, typically through internet platforms) and electronic payment institutions (e-money companies that offer issuance, administration, accountability, redemption, and the transfer of electronic payment funds through electronic or digital means).

Cryptocurrencies: The Law regulates transactions with cryptocurrencies, also defined as virtual assets, and entrusts the Central Bank with oversight. The Central Bank authorizes all transactions made by financial and FinTech institutions with virtual assets. The Law does not regulate cryptocurrencies but their entry into the financial system.

A Regulatory Sandbox: The Law also creates a trial space for innovative models in a controlled scenario. Under this “sandbox scheme,” a temporary authorization is granted to FinTech companies allowing them to undertake regulated activities with the purpose of testing out new business models under close monitoring. The concept of a regulatory sandbox has been proven to be successful in other jurisdictions, like the United Kingdom and Singapore, and has positively contributed to the development of their respective FinTech industries.

Open Banking and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs): The FinTech Law also includes the concept of open banking and requires all institutions within the financial system, including FinTech companies, to establish Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) which are a set of computing protocols for building software applications. An API is a software that allows two applications to communicate with each other. The purpose of requiring APIs in the financial system is to allow access and connectivity within financial institutions to share users’ open financial, aggregated, and transactional data (with users’ consent); and offer optimal services and products by improving their websites and mobile apps. APIs in the financial system allows for the facilitation of secure transactions between institutions, the analysis of market data and risk, and payment processing.

The FinTech Industry and Ensuring Financial Inclusion in Mexico

In Mexico, the disparity between thriving banks and the low levels of financial inclusion as a result of high barriers of access to financial services and a shortage of credit supply to relevant sectors of the economy is notable.

FinTech companies promise to be an alternative source of finance with the potential of mitigating this disparity. With more than fifty percent of Mexico’s population unbanked but, at the same time, with high rates of internet penetration and smartphones technology per capita, the emergence of FinTech companies is timely and could match these missing dots.[20]

FinTech companies have the potential to reshape the dynamics of the financial system by introducing innovative ways to provide financial services such as credit, savings, insurance, and payments. Although the industry is small and new, it is possible to anticipate that in the future, when FinTech companies grow and consolidate in the market, there will be an increase in competition in several segments, mainly in the credit markets, which in turn would represent a reduction in profit margins for traditional intermediaries like banks. Those intermediaries would have to adjust to new FinTech competitors by reducing costs, expanding financial offerings, or partnering with FinTech companies.

There are some uncertainties about the future of the FinTech industry in Mexico given that the impact of the new regulations on this nascent industry is still unknown. Although it is too soon to assess the implications of the FinTech Law in Mexico, it has been observed that in more consolidated markets like in the United Kingdom or Singapore, the existence of adequate regulation provides stability and fairness, and favors the growth of financial innovations. Nevertheless, in Mexico, there is a risk that the FinTech Law might represent an excessive burden and end up slowing down or preventing further innovation in the coming years. If that is the case, then FinTech companies might be unable to deliver the promises to offer more funding options and provide better and affordable services in a wider manner to the unattended groups in the economy. Furthermore, there are also some concerns about the real contributions of FinTech companies to financial inclusion. For instance, according to the data available from one of the leading P2P platforms in the country, Prestadero,[21] more than sixty percent of the total volume financed through the platform has been used for refinancing debts or restructuring banking and credit card loans, which reveals that the main users of these platforms are an already banked population and the model is not fully reaching unattended individuals.

The provision of financial services to society cannot be a task of only one sector. The financial inclusion challenge is a great one and FinTech companies cannot be the sole sector tasked with solving it. The CONAIF has recognized the necessity of an integral approach to come up with an appropriate strategy to address gaps in the financial system and provide quality services to society in a coordinated manner. Contributions from relevant stakeholders such as financial regulators, local and federal governments, private financial institutions, and non-profit organizations are necessary for a holistic response that tackles the issue of financial inclusion. Financial inclusion should not be understood as the provision of more credit cards or ATMs, but rather the provision of a full range of financial services paired with financial education and functional infrastructure.

Two main lessons can be drawn from the FinTech Law drafting process. First, after an extensive debate between the members of the FinTech industry and financial regulators, a consensus was reached for the passage of the Law. This experience should be taken into account in the development of further regulations or adjustments to the regulatory framework. The open and shared dialogue between regulators and FinTech companies is essential for the growth of the industry. Second, as acknowledged in the 2016 National Program for Financial Inclusion Report, in Mexico, there are no evaluations showing the impact of financial inclusion on the income level or well-being of households. Moving forward, it is important to keep track and assess the impact of this new regulation. The Law establishes a number of mechanisms through which these assessments could be conducted. An example of one mechanism that is already implemented in Mexico is the Financial Stability Board (CESF by its Spanish acronym). The CESF is a coordinated group where the main regulators of the financial system exchange ideas and conduct evaluations to analyze risks within the financial system.

The technological innovation applied by FinTech companies in financial markets has the potential to address existing credit gaps, increase the supply of financial services, and lower the costs of providing them to unattended individuals. More competition in financial markets would foster lower costs, better options, and a better provision of services. While the FinTech Law is a powerful resource to achieve better benefits to Mexican society, FinTech alone cannot be thought of as the ultimate response to achieve financial inclusion. Opening spaces for discussion and analysis among the private sector, financial authorities, non-profit organizations, and civil society could be an important mechanism to promote financial inclusion in a holistic manner. The adequate involvement of each stakeholder is essential to ensure financial access and the provision of financial education. FinTech companies should not be seen as the sole solution to the challenge of meeting the financial needs of unattended households and small enterprises but rather as important contributors and partners in the fight against financial exclusion.

References

- World Bank, Financial Inclusion – Overview, 2018. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview ↑

- “Speech by Governor Brainard on the Opportunities and Challenges of Fintech,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2018. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20161202a.htm. ↑

- National Banking and Securities Commission, “National Council for Financial Inclusion,” (2018) https://www.cnbv.gob.mx/en/Inclusion/Paginas/CONAIF.aspx. ↑

- International Monetary Fund, “Financial Access Survey Data,” 2011, accessed August 30 https://bit.ly/2ChtvKb ↑

- International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook Database, April 2018,” https://bit.ly/2AzJRuJ ↑

- World Economic Forum. 2012. “The Financial Development Report.” USA, page 195. ↑

- World Bank, “Global Financial Inclusion database,” accessed August 30 http://databank.worldbank.org/data/source/global-financial-inclusion/ ↑

- Ortiz, Guillermo. 2013. “Perspectives on Financial Inclusion from Mexico.” Speech at “Bridging the Gap: How Can Banks Reach the Unbanked?” Research Conference organized by The SWIFT Institute, The Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, The Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, The Harvard Kennedy School, 2013. https://swiftinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Guillermo-Ortiz-SWIFT-Institute-FIRC-280213.pdf ↑

- Beck, Thorsten, and Asli Demirgüç-Kunt. 2008. “Access to Finance: An Unfinished Agenda.” The World Bank Economic Review 22 (3): 383-396Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Patrick Honohan. 2009. “Access to Financial Services: Measurement, Impact, and Policies.” The World Bank Research Observer 24 (1): 119-145

Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, and Ross Levine. 2007. “Finance, Inequality and the Poor.” Journal of Economic Growth 12 (1): 27-49 ↑

- Financial Stability Board, “Financial Stability Implications from Fintech – Supervisory and Regulatory Issues That Merit Authorities’ Attention,” (2017). http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/R270617.pdf. ↑

- Finnovista, “Finnovista Radar Mexico 2018,” https://www.finnovista.com/actualizacion-finnovista-fintech-radar-mexico-2018/?lang=en ↑

- Finnovista, “Finnovista Radar Mexico 2018,” https://www.finnovista.com/actualizacion-finnovista-fintech-radar-mexico-2018/?lang=en ↑

- Finnovista, “Finnovista Radars,” https://www.finnovista.com/tag/fintech-radar/ ↑

- Financial Stability Board, “Financial Stability Implications from Fintech – Supervisory and Regulatory Issues That Merit Authorities’ Attention,” (2017). http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/R270617.pdf. ↑

- Ziegler, Tania, E.J. Reedy, Annie Le, Bryan Zhang, Randall S. Kroszner, and Kieran Garvey. 2017. “The Americas Alternative Finance Industry Report.” Chicago Booth School of Business, Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, 2017. https://polsky.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/AmericasAltFinReport.pdf. ↑

- Finnovista, “Finnovista Radar Mexico 2018,” https://www.finnovista.com/actualizacion-finnovista-fintech-radar-mexico-2018/?lang=en ↑

- Ziegler, Tania, E.J. Reedy, Annie Le, Bryan Zhang, Randall S. Kroszner, and Kieran Garvey. 2017. “The Americas Alternative Finance Industry Report.” Chicago Booth School of Business, Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, 2017. https://polsky.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/AmericasAltFinReport.pdf. ↑

- Carletti, Elena, and Xavier Vives. 2008. “Regulation and Competition Policy in the Banking Sector.” IESE Business School, Public-Private Sector Center, 2008. ↑

- Robles-Peiro, Rocio H. 2015. “Crowdfunding: Reasons for its regulation (In Spanish).” Instituto Iberoamericano de Mercados De Valores, 2015. ↑

- Antoni, Federico. 2016. “The Rise and Rise of Mexican Fintech.” Techcrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2016/07/28/the-rise-and-rise-of-mexican-fintech ↑

- Prestadero – Statistics.” 2018. Prestadero.com. Accessed August 30. https://prestadero.com/stats_destinos.php. ↑