Written By Minglei Gao

Edited By Eghosa Asemota

With the slowing growth in investment and exports over the past few years, China is transitioning into an economy that will rely more heavily on domestic consumption rather than on foreign investment and exports. In 2017, China’s final consumption accounted for 58.8 percent of the total GDP growth. Though China’s consumption, both foreign and domestic, were high, its consumer protection regime lagged behind and consumers were not given sufficient protection in market transactions. Fake products, a lack of food and drug safety standards and deceptive market practices resulting from the inadequate regime have made consumers restrain from purchasing luxury goods, baby foods and electronic appliances. To stimulate domestic consumption and recover consumers’ confidence in domestic products, China’s existing consumer protection regime must be improved. This article provides an overview of the current consumer protection regime in China, examines the impetus behind the government’s shift in concern and prioritization of it, and offers policy recommendations for the development of a regime that provides more effective, efficient and strong protection to consumers.

Background: China’s Consumer Protection Regime

Consumer protection has a relatively short history in China. The concept initially came to public attention in 1993 with the enactment of the Consumer Protection Law (also known as The Consumer’s Right and Interests Protection Law). Since then, consumer protection in China has gradually expanded as seen in the development of legislation, the creation of overseeing institutions and the national media’s commitment to generating public awareness.

On the legislative level, consumer protection is codified in three major laws – The Product Quality Law (1993), The Consumer’s Rights and Interests Protection Law (1993) and the Food Safety Law (2009). The Product Quality Law, enacted in February 1993, instituted the oversight of production and product quality. The law imposes liability and obligations on producers, and establishes compensation and penalty mechanisms.[1] Building on The Product Quality Law, The Consumer’s Rights and Interests Protection Law, enacted shortly afterward, was the first piece of legislation in China’s history that prioritized the defense of personal safety and the maintenance of property. The law also provides consumers with the right to injury compensation, information disclosure from business operators and freedom of choice in market transactions.[2] The Food Safety Law, later revised in 2015, sets higher standards for public health and enforces severe penalties for violation of food quality regulations.[3]

The national institution that regulates industries and market practices is the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC). As the watchdog for consumer protection in China, SAIC creates regulations and continually inspects product quality in nearly all industries.[4] Another national institution that has positively contributed to consumer protection is the China Consumer Association (CCA), which deals with consumer complaints and protects consumers’ rights and interests. Since its founding in 1984 by the State Council, the CCA has developed 3,279 local branches at the county and state level. The CCA was formally defined by the Consumer Protection Law as a social organization that solely protects the interests of registered consumers who pay membership fees.[5] During this time, awareness of consumer protection among the public was not prominent. Resultantly, CCA’s membership was small and limited funding in its local branches led to the inefficiency of the organization for many years. A revision to the Consumer Protection Law in 2015 changed the nature of the CCA from an exclusive social institution to a national association that deals with all consumer complaints. Now a public entity, the association is sponsored by the government, which ensures more stable operations and protects all consumers by filing lawsuits targeting deceptive market practices.[6] Ming Jian is another prominent institution that prioritizes consumer protection. As a member of the International Consumer Research and Testing (ICRT), Ming Jian conducts independent testing on product quality and performance.[7]

The most significant measure in China for consumer protection occurs through national media. “San Yao Wu,” also known as China’s Consumer Rights Day, is a show held on March 15 of each year where deceptive producers and corrupt market practices are exposed to consumers nationwide. Reporters use hidden cameras to reveal unknown facts within corporations. A notable example that attests to the impact the national media has on the consumer protection regime was seen in the 2011 Shuanghui ham scandal, where China Central Television (CCTV) revealed that Shuanghui, a major meat producer in China, added clenbuterol to their hams in order to increase the net content of lean meat. Clenbuterol is a banned food substance in China proven to result in a higher risk of heart disease. After this practice was exposed by CCTV, several Shuanghui executives were removed from their positions. As a result of consumer mistrust, the company lost its advantageous position in the market and has failed to recover from the incident ever since.[8] In recent years, San Yao Wu has grown more visible, and the uncovered information has led to heated discussions. Businesses undergirded by deceptive practices were significantly impacted with declines in revenue. In response to the media’s reports, policymakers have started to make further regulations to combat and deter unfair and hazardous practices. Collectively, the media’s approach has greatly increased public awareness and fortifies the protection of consumer rights and interests in China.

Centralizing Consumer Protection: What Has Changed?

China’s neglect of consumer protection prior to the enactment of The Consumer’s Rights and Interests Protection Law (1993) stems from the actions the country undertook to improve its economic status in the mid-20th century. In response to its underdeveloped economy resulting from a lack of production, China sought to boost industrialization in the 1950s with the adoption of an imbalanced policy. The policy affirmed that “production [was] to take precedence over consumption”. This guiding principle would “raise the society’s living standards and construct a socialist economy”.[9] Decades later, investment and exports became the major driving forces of the economy, while domestic consumption contributed less to China’s economic growth comparatively.

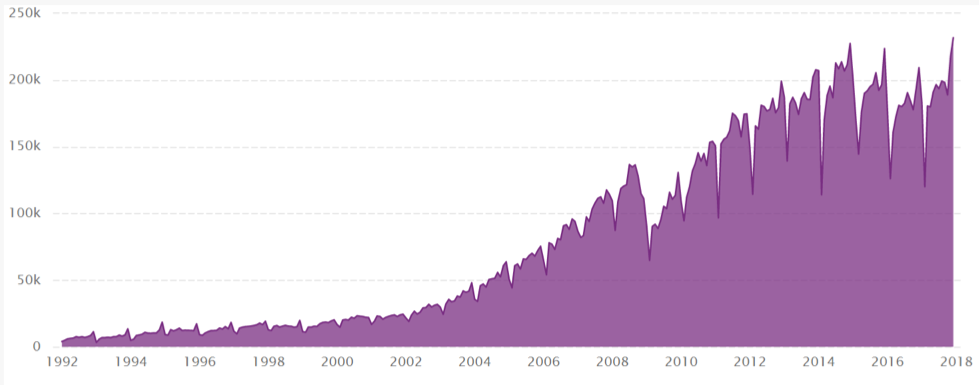

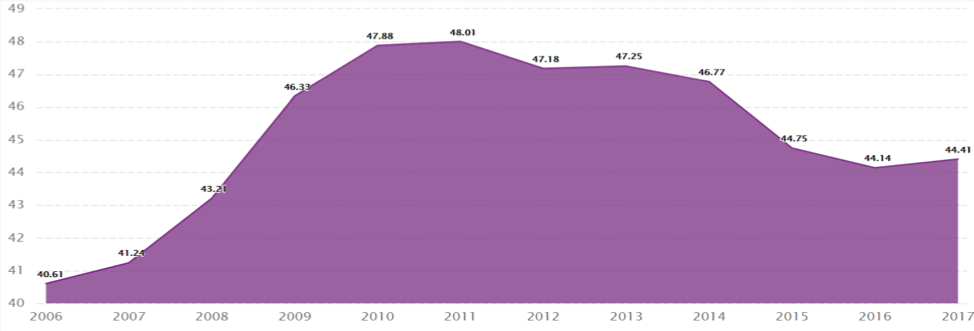

Since then, China’s economic growth has largely relied on foreign export and investment. However, though total exports reached its climax in 2014 and investment reached its peak in 2011, export and investment in China has since declined as seen in Figures 1 and 2. According to a review by Kuo, “China’s consumer economy is projected to reach $6.5 trillion in annual private consumption by 2020, even if GDP growth cools to 5.5%”.[10] Domestic consumption is therefore expected to be the major force driving China’s economy in the next few decades.

Figure 1: China’s Total Exports from 1992 to 2018 (CEIC)[11]

Figure 2: China’s Investment: % of GDP from 2006 to 2017 (CEIC)[12]

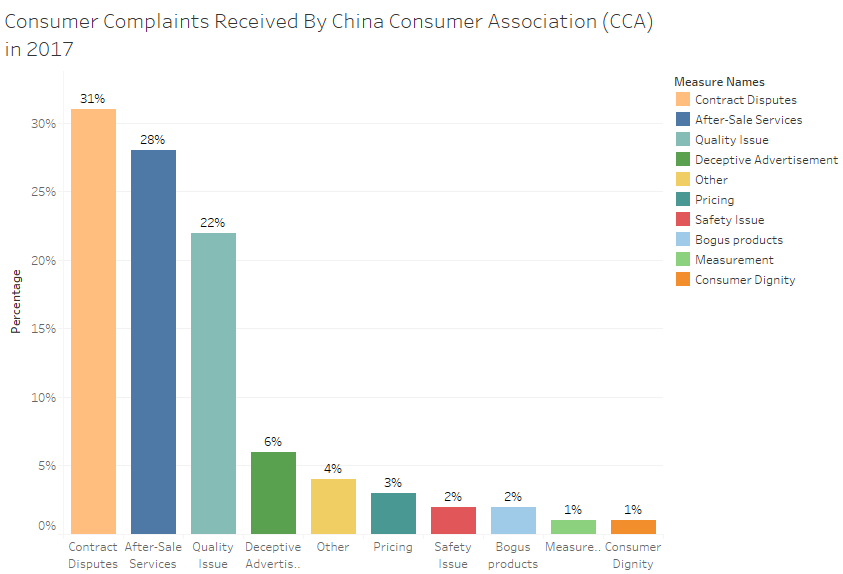

With China centering domestic consumption in its economic development agenda, the country recognizes the need for a sound consumer protection regime that improves consumers’ rights and builds consumer trust. While strides have been made to protect consumers’ interests, however, the consumer protection regime still lags behind. The China Consumer Association (CCA) is the only national association that deals with consumer grievances. In 2017, the CCA reported that it received 726,840 complaints and 76 percent of them were resolved.[13] Figure 3 shows that quality issues, contract disputes, and after-sale services are still major problems for consumers in 2017. Also, with the final consumption expenditure accounting for 58.8 percent of China’s economic growth in 2017, it is believed that the incidence of consumer injury caused by defective products and complaints about deceptive marketing practices are substantially higher than what has been reported.[14]

Figure 3: Consumer Complaints Received by China Consumer Association (CCA) in 2017 (SAIC of the PRC)[15]

Given the incidence of consumer injury, it is clear that consumers still do not have sufficient protection in their market transactions. Fake products, a lack of food and drug safety regulations and deceptive market practices have deterred the domestic purchase of luxury goods, baby foods and electronic appliances. Granted, China’s consumer protection regime did see great improvement in 2013, when the Consumer’s Rights and Interests Protection Law was amended for the first time in 20 years, adding clauses that cover e-commerce and private information protection, and instituted stricter safety and quality obligations as well as punitive damages.[16] Nevertheless, most consumer protection laws have not evolved despite dramatic market changes over the last decade and most consumers lack a public avenue to appeal to and protect their rights.

Consequently, the government is working to empower consumers dealing with conflicts with producers, regulate information credibility, and monitor product quality and food safety to make the domestic market more trustworthy for consumers. Specifically, under their consumption-led economic development policy, agencies that oversee the consumer protection regime and producers are expected to join forces to 1) cultivate a social culture of domestic consumption; 2) improve consumers’ access to goods and services; 3) innovate to satisfy the demands of different consumer classes; and 4) provide more financial assistance to consumers for purchasing.[17] At the core of this initiative is the government’s desire to maintain a healthy, just and stable market where the power of private parties is balanced with empowered and well-informed consumers.

Mapping the Shortcomings of China’s Current Consumer Protection Regime

With discourse looming on how to fortify the consumer protection regime, it is imperative that policymakers address notable shortcomings within the current policy in the near future, namely the lack of collaboration between the institutions pooling consumer complaints and regulating market operations, and the high cost of class action suits to consumers.

The separation of consumer complaints and business regulations, spearheaded by two distinct institutions, hampers the possibility of adequate consumer protection. While the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) oversees and regulates market practices for consumer protection in nearly all industries, the China Consumer Association (CCA) receives nationwide consumer complaints and handles them on a case-by-case basis. Counterintuitively, though both institutions share a common objective, little contact is made by them. The CCA, which works to resolve disputes and facilitate compensation agreements between individual consumers and producers, abstains from conducting deeper investigations into the producer and industry nor does it relay reports to the SAIC for further inquiry. Instead, the SAIC runs its own tests and investigations on target industries independently. The lack of interdependence between the CCA and the SAIC contributes to avoidable consumer harm. In instances where injured consumers appeal their cases to the CCA and get compensated, the producer can still continue their deceptive practices with other consumers without government intervention.

Another issue with China’s current consumer protection regime is reflected in the massive costs for individual consumers who want to fight private producers for deceptive practices through class-action lawsuits. Consumers tend to incur four types of costs. The first, information costs, refers to the cost of informing other consumers of unfairness in these market practices.[18] The second, monitoring costs, is the cost of gathering all other consumers who are harmed by these practices and getting them to participate.[19] The third, the cost of appealing for support from the China Consumer Association. Unlike consumers in the United States, who are allowed to form a group to sue producers together in court, class-action lawsuits cannot be spearheaded by consumers in China – “only government-controlled consumer associations are allowed to launch such suits”.[20] Persuading the government body to launch a suit against a producer requires substantial evidence, written documents, and an effective communications campaign. Lastly, Chinese consumers are also responsible for the costs of product testing. Product testing refers to the evaluation of product performance to identify harmful deficiencies. To initiate lawsuits, consumers have to gather concrete evidence from third-party testing institutions and assume all the costs of product testing. As China transitions into an economy dependent on domestic consumption, both of these issues must be resolved in order to create a more effective regime that adequately protects consumers.

Developing a More Effective Consumer Protection Regime

To develop a more effective consumer protection regime, there must be substantial incentives for producers to follow regulatory rules and more legal participatory opportunities for consumers in solving disputes. Since the establishment of the regime, Chinese industries have passively considered market regulation and consumer protection. Although market regulations through executive government agencies usually come with strong enforcement and effective results, government officers often do not understand the industries as well as market participants themselves. As a result, some deceptive practices remain undetected.

A policy encouraging self-regulation by industrial associations would allow for industries to find problems themselves and seek options to address conflicts with its consumers. Large industrial associations such as the China Software Industry Association, the China Pharmaceutical Industry Association and the China Iron and Steel Association currently focus on academic communications, information disclosure and providing their respective services. Under this policy, industries such as these would establish committees that oversee their member companies’ practices, while government agencies monitor these industries’ self-regulating processes and impose stricter statutes only if their self-regulation is found to be ineffective. If the CCA still receives massive consumer complaints regarding issues that reveal the ineffectiveness of industry self-regulation, it would trigger direct government investigations into the industry and stricter regulations would be imposed. Such a policy would incentivize self-regulation since stricter directives imposed by the government could harm the interest of the industry as a whole. The policy would also give consumers an additional avenue to report complaints. Moreover, the policy would combine complaints and regulations into one collaborative process, and contribute positively to consumer protection and the maintenance of a fair and just market.

Market practices and private producers are mainly regulated in China through executive agencies instead of courts and Chinese consumers are not given sufficient legal support from government-controlled consumer associations. In individual consumer injury cases, consumers face the huge cost of launching lawsuits against powerful private producers for compensation. When solving the complaints, the associations use executive power to facilitate a compensation agreement on a case-by-case basis but are not required to provide legal support for consumers launching private lawsuits. This results in fewer injury lawsuits against deceptive producers and does not help to deter deceptive practices in the market. To improve the effectiveness of current consumer protection regime, legal assistance should be made available at consumer associations where consumers can receive help from professional lawyers.

As only government-controlled associations can launch class-action lawsuits in the country, there should be a policy requiring more legal participation of consumer associations. China Consumer Association has done a commendable job in advocating for regulations to Apple Inc. and defending Chinese consumers against the unfair contract clauses regarding repair policies.[21] In the future, a policy is needed to establish clear standards of what legal participation is required of and what working dynamics must exist between associations and harmed consumers to constructively join forces in legal affairs.

Note: Quantitative evaluation of the budding consumer protection regime is in its preliminary stage and the author could not obtain sufficient data regarding consumer injury cases, market conflicts and lawsuits when writing this article. In future research regarding consumer protection policy, the author calls for an emphasis in data collection and quantitative monitoring by government executive agencies regarding consumer protection.

References

- Marlerblog. 2004. “Product Quality Law of The People’s Republic of China.” Marlerblog. http://www.marlerblog.com/uploads/file/chinaproductliability.pdf ↑

- World Intellectual Property Organization. n.d.. “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of Consumer Rights and Interests.” World Intellectual Property Organization.https://www.economist.com/news/business/21599006-chinas-new-consumer-law-has-local-and-foreign-firms-worried-true-meaning-san-yao-wu ↑

- Lin Fu. 2016. “What China’s New Food Safety Law Might Mean For Consumers And Businesses.” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2016/05/13/what-chinas-new-food-safety-law-might-mean-for-consumers-and-businesses/ ↑

- Taylor Wessing. 2016. “Protecting the People: China’s Consumer Law.” Lexology Publishing. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=bb1fd060-4d78-4a9f-9521-d753ffb9cf29 ↑

- Xu, Wei. 2013. “Revised consumer law to strengthen association.” China Daily. http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013-10/31/content_17070423.htm ↑

- Congressional-Executive Commission on China. 2014. “Amendments to Consumer Protection Law Allows for Public Interest Lawsuits With Limitations.” Congressional-Executive Commission on China. https://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/amendments-to-consumer-protection-law-allows-for-public-interest ↑

- Feldkamp, James. “Mingjian, Testing For Safe Quality Products In China.” Cornerstone Capital Group. https://cornerstonecapinc.com/mingjian-testing-for-safe-quality-products-in-china/ ↑

- China Daily. 2011. “Shuanghui Apologizes for Additive Scandal.” China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2011-03/17/content_12185197.htm ↑

- Suk‐ching Ho, and Yat‐ming Sin. 1988. “Consumer Protection in China: The Current State of the Art.” European Journal of Marketing, 41-46. ↑

- Kuo, Youchi. 2016. “Three Great Forces Changing China’s Consumer Market.” World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/3-great-forces-changing-chinas-consumer-market/ ↑

- CEIC. 2018. “China’s Total Exports.” General Administration of Customs. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/china/total-exports ↑

- CEIC. 2017. “China Investment: % of GDP.”CEIC. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/china/investment–nominal-gdp ↑

- China News Network. 2018. “In the Consumers Association: 2017 year over 720,000 complaints over the resolution rate of 76%.” China News Network. http://westdollar.com/sbdm/finance/news/1355,20180129826664591.html ↑

- Reuters. 2018. “Final consumption accounted for 58.8 percent of China’s 2017 GDP growth – stats bureau.” Reuters. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-china-economy-consumption/final-consumption-accounted-for-58-8-percent-of-chinas-2017-gdp-growth-stats-bureau-idUKKBN1F70U5?il=0 ↑

- China Consumer Association. 2017. “Consumer Disputes Case Portfolios in 2017.”State Administration of Industry & Commerce of PRC. http://home.saic.gov.cn/sj/tjsj/201801/t20180130_272126.html ↑

- Zhang, L. 2014. “China: Consumer Protection Law Revamped for First Time in 20 Years.” The Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/china-consumer-protection-law-revamped-for-first-time-in-20-years/ ↑

- Keely, Louise and Anderson, Brian. n.d.. “Sold in China: Transitioning To A Consumer-Led Economy” Demand Institute. http://demandinstitute.org/demandwp/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Sold-in-China.pdf ↑

- Tennyson, Sharon. 2018. “Lecture 6: Political Economy [PowerPoint slides].” Cornell University Economics of Consumer Policy Blackboard. https://blackboard.cornell.edu/webapps/blackboard/content/listContent.jsp?course_id=_78493_1&content_id=_3665052_1 ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- The Economist. 2014. “The true meaning of san yao wu.” The Economist. https://www.economist.com/news/business/21599006-chinas-new-consumer-law-has-local-and-foreign-firms-worried-true-meaning-san-yao-wu ↑

- Kan, Michael. 2012. “Chinese watchdog group takes aim at Apple repair policies.” Computerworld. https://www.computerworld.com/article/2504693/data-center/chinese-watchdog-group-takes-aim-at-apple-repair-policies.html ↑