Source: Todd Bragstad/Biz Journals

Written by: Grace Barlow, Jose Basaldua, Leah Holloway and Angeline Koch

Edited by: Eghosa Asemota

The Great Lakes Compact, a legal contract between the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, was created in conjunction with a similar legal agreement between the Canadian Provinces of Ontario and Quebec. This document, also referred to as the Compact, was signed into law in 2008 and outlines how states and provinces within the Great Lakes Basin will collectively manage the use of the Great Lakes’ water supply. While the Compact has a wide range of goals, special emphasis is placed on ensuring that the Great Lakes’ water remains within the natural basin boundaries and that it is used sustainably and responsibly.[1]

As the authors of the Compact carefully crafted this document over seven years, they kept watch over a particular situation developing in southeast Wisconsin. The drafters believed, with good reason, that the City of Waukesha would present the first major test of the Compact. They were right. The ink on the Compact was barely dry before Waukesha, which lies just outside the Lake Michigan Basin, submitted its application to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) for a diversion of Lake Michigan water. After an eight-year battle, Waukesha received approval for their request to divert Great Lakes water to its municipality. However, Waukesha’s gain is not without negative impacts to other communities. Parties involved in the decision-making process gave little to no consideration to the environmental justice implications of the diversion, despite expending hundreds of thousands of dollars for environmental and legal analysis during an eight year application process. This paper will outline the driving reasons behind the current state of the Waukesha diversion plan and analyze the environmental justice concerns for communities in Southeastern Wisconsin. The analysis will utilize two frameworks, Systems Thinking and Schlosberg’s Dimensions of Environmental Justice, and will focus particularly on the impacts of Waukesha’s return flow plan through the Root River. This case study describes how Waukesha changed its plan to return its wastewater from a river that flows through a largely White, middle class community, to one that flows through a largely minority, lower income community, after protest from the middle class community. The case study also identifies intervention points where Waukesha could make changes to minimize the impact of the diversion on certain communities and be a positive model for how Great Lakes Compact diversions could be done equitably in the future.

Dimensions and Systems Thinking

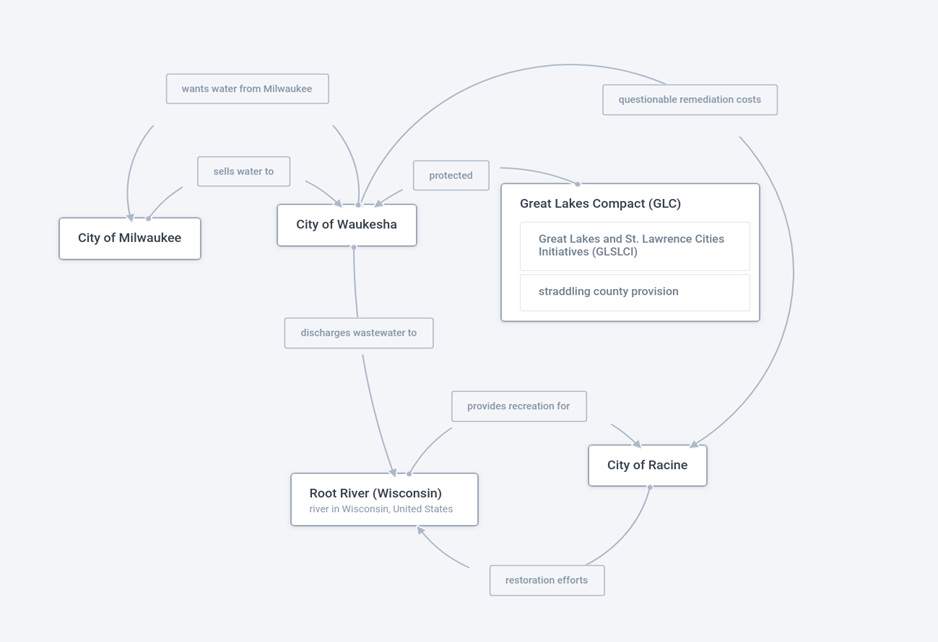

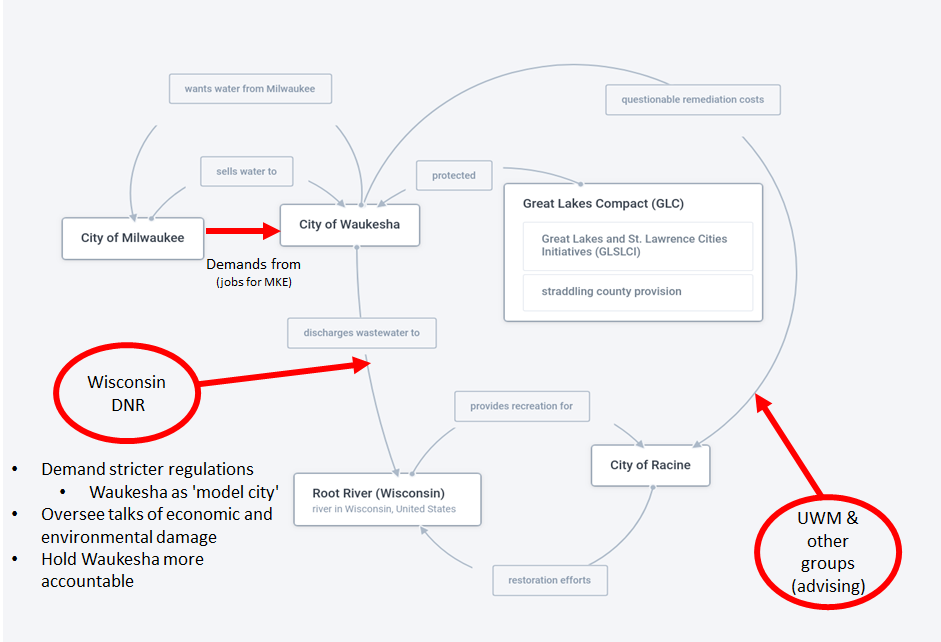

There are two frameworks for analyzing environmental justice issues: Systems Thinking and the Dimensions of Environmental Justice. These frameworks allow for a thorough examination of the environmental justice issues and provide methods to analyze potential intervention points and mitigate any injustices found. Systems Thinking, also referred to as DSRP, uses a holistic approach to ensure that all relevant pieces of a problem are considered. DSRP breaks problems down into four main components: distinctions, systems, relationships, and perspectives.[2] This framework helps users to address multifaceted problems by approaching the problem from different angle which allows for a more effective assessment of potential solutions and stakeholders. The distinction rule of DSRP states that “any ‘idea’ or ‘thing’ can be distinguished from other ‘ideas’ or ‘things’ within the system.” This is achieved by designating specific ideas as “identities.”[3] The system rule is defined as “any idea or thing that can be split into parts or lumped into a whole” and helps identify what aspects of a problem may be separated from the rest.[4] The relationship and perspective rules take both the identities and systems defined by the distinction and system rules and relate them to each other, other system components, and relevant perspectives. DSRP is a helpful tool for working through environmental justice issues, where unconscious biases and marginalization are often central to the problem. For this discussion of environmental injustices and the Waukesha Diversion, a DSRP map (Figure One) was created to aid the analysis.

|

|

Figure 1: A DSRP/ Systems Thinking Map of the Waukesha Diversion Case |

The DSRP map illustrates the important distinctions and the systems they create for the Waukesha diversion case. The map also portrays the relationships between Waukesha and Milwaukee as a transaction. Waukesha will obtain Lake Michigan’s water from the City of Milwaukee but has yet to finalize a route for returning used or treated wastewater to Lake Michigan. Initially, engineering consultants determined that the return flow from Waukesha to Lake Michigan should be routed via Underwood Creek. After the return flow plan was published to the community, Waukesha changed its return flow route from Underwood Creek to the Root River, which flows through the City of Racine. The Racine community enjoys a long standing commitment to the ecological health of the Root River which winds through their city. Residents recreate on the river, have businesses that are connected to the river, and are vested in the river’s ecological health and integrity. These areas of interest will be expanded further in later sections of this discussion, including an analysis of Waukesha’s commitments regarding the level of water quality of the discharge effluent and Waukesha’s potential lack of accountability for environmental impacts.

The second framework for analyzing environmental justice issues, “The Dimensions of Environmental Justice,” is derived from David Schlosberg’s 2004 essay “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories.” Schlosberg expanded the idea of environmental justice that traditionally looked at whether pollution was distributed equitably among racial and economic demographics to include the ideas of recognition and participation. In his paper, Schlosberg argued that part of the problem of traditional environmental injustice theory is the lack of recognition of differences among communities based on race, ethnicity, or economic status.[5] An unacknowledged, marginalized community includes various forms of degradation and devaluation at both the individual and cultural level.[6] While it is important to recognize that environmental injustices are often centered around unequal distribution of pollution with marginalized groups bearing the brunt of pollution, uneven access to environmental resources, or environmental policy that focuses solely on addressing uneven distribution of pollution, is not adequate to restore justice. Instead, when looking to address and analyze issues of environmental justice, the decision-making process should recognize and prioritize the participation of marginalized groups.

Distributional justice observes the apportionment of environmental burdens and benefits throughout society. Unfortunately, many impoverished communities and communities of color in the U.S. are allotted a disproportionate share of society’s environmental burdens. One burden shouldered disproportionately by impoverished communities is the disposal of wastewater into their local waterways. The release of untreated wastewater has the very serious potential of contaminating and poisoning the public and of destroying local ecosystems.[7] The situation can be made worse if an affected community relies heavily on local ecosystem services for sustenance and economic support. Not having a strong voice and not being allowed to participate in the decision-making process often results in distributive injustice. Communities of color and impoverished communities have lower property values as compared to middle-class communities with a White majority. As such, it costs less for industries to buy land in communities with depressed land value. In addition, industries can set up operations with little to no opposition by residents who often have less access to information and are not often equipped to organize an opposition. In turn, these communities are exposed to a disproportionate amount of environmental pollution, including untreated wastewater. This situation was analyzed in a 2016 study in southern Texas that focused on the disproportional location of fracking wastewater disposal wells.[8] The study found that most wells were located in closer proximity to residents of color and living in poverty than near non-Hispanic White communities.[9]

The theory that recognition deepens the understanding and full impact of distributive injustice also establishes “the direct link between a lack of respect and recognition and a decline in a person’s membership and participation in the greater community, including the political and institutional order.”[10] The dimensions of an environmental justice analytical framework provides an in-depth analysis for the potential environmental justice concerns raised by the Waukesha diversion plan.

Before addressing Waukesha’s need for a Lake Michigan diversion and the analysis of environmental justice issues, it is important to understand the legal basis and policy of the Great Lakes Compact and related Wisconsin Department of Natural Resource statutes. The main legislative components of the Compact include a ban on future diversions and a requirement that each participating state or province develop a water management program based on elements required by the Compact.[11] The ban on future diversions provides that no community outside of the natural basin boundaries of the Great Lakes may move water out of the basin. However, because the political and the geological basin boundaries do not perfectly align, the Compact outlines two exceptions for communities that may apply for a diversion of the Great Lakes’ water. Communities whose political boundaries lie partly within the basin, such as New Berlin, Wisconsin, are referred to as “straddling communities.” Communities that are located in a county whose border lies partially on the basin line, such as Waukesha, Wisconsin, are referred to as “communities within straddling counties.” While both may apply for a diversion, the type of community plays a role in determining to which requirements a community must adhere. Both the Great Lakes Compact and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources outline requirements, summarized in Figure Two, for diversion approval. Requirements for communities within straddling counties, such as Waukesha, are more stringent.

| Straddling Community |

Per the Great Lakes Compact:

|

| Community Within a Straddling County |

Per Wisconsin DNR Straddling County Requirements:

|

Figure 2: Great Lakes Compact and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resource Requirements[12]

The Great Lakes Compact and WDNR statutes are important components, vital to understanding the environmental justice issues surrounding the diversion. These requirements are the current framework for any community looking to access the Great Lakes’ water, of which Waukesha is the first with a contentious application. The diversion requirements, whether they be from the Compact itself or from the WDNR, provide proponents and opponents of the diversion, the basis on which to argue the permissibility of Waukesha’s request. This provides an interesting element to the discussion as both sides use the statutes and requirements to bolster arguments about the need to access safe drinking water, or their worry that the diversion will have negative ecological impacts on the Lake Michigan watershed and open the door for future diversions.

In particular, the WDNR requirement regarding the treatment and water quality standards of the return flow water– and the biological, chemical, and physical integrity of any waters receiving this return flow water– is important to the Waukesha Diversion discussion. In the application, Waukesha stated that their withdrawal would not have negative environmental impacts on the biological, physical, and chemical integrity of the Root River, Lake Michigan, or other waters in the basin, and that their return flow “will be treated to meet applicable water quality standards” and “provide more, and higher‐quality, functional in‐stream habitat improvements to the biological integrity of the Great Lakes tributary receiving return flow.”[13] The City has maintained this position in subsequent documents throughout the diversion process, with this stance being a major point of contention between Waukesha and opposing voices.

The Need for a New Source of Water in Waukesha

Another largely contested part of Waukesha’s application revolved around the Compact requirement for a community within a straddling county to demonstrate that it is “without adequate water supply and that there is no adequate alternative for water supply.”[14] Waukesha, Wisconsin is a suburb of Milwaukee that sits seventeen miles west of Lake Michigan, and one and a half miles outside of the Great Lakes Basin. Waukesha has a population of just over 72,000, making it the seventh largest municipality in the state.[15] It is seventy-eight percent White, twelve percent Hispanic, four percent Asian, four percent Black and two percent other.[16] Its median household income is $59,500, which is slightly higher than Wisconsin as a whole, and Waukesha has an eleven percent poverty rate.[17]

|

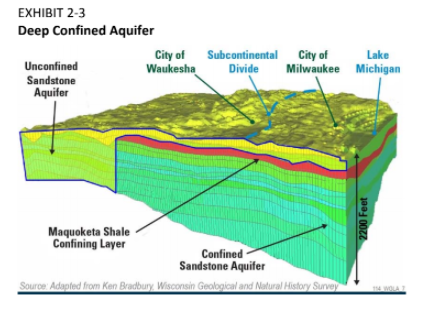

Figure 3: Geological Map of the Confined Aquifer

Currently, Waukesha uses seven deep wells in the St. Peter confined sandstone aquifer (Figure Three) that extend beneath Waukesha all the way east to Lake Michigan, and three shallow wells in the Troy Bedrock Valley aquifer to the west, to obtain its public water supply.[18] Some of the deep wells are over seventy-five years old, and draw water from up to 1000 feet below the surface; the shallow wells are newer,most of which are less than twenty years old, and were put online to help mitigate Waukesha’s increasing radium problem.[19]

As the population of the western Milwaukee suburbs began to grow, water withdrawals increased. Soon, more water was being drawn from the St. Peter Aquifer than could be replenished by annual precipitation, and water levels in the aquifer began to drop. Natural sources of radium became more concentrated the more the aquifer was drawn down, and this began to contaminate the region’s drinking water supplies.[20] In 2000, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced more stringent radium regulations in order to protect citizens from this known carcinogen in their drinking water. Waukesha’s water had more than three times the allowable standard.[21] Waukesha’s initial response was to sue the EPA and discourage implementation of reduced radium restrictions.[22] When that failed, Waukesha decided to dig wells in the Troy Bedrock Valley to dilute the water supply enough to reduce radium concentration. While these wells helped reduce the levels of radium in drinking water supplies, Waukesha still does not consistently meet the standard for radium concentration in its public drinking water supply, especially during periods of high water use.[23] As such, Waukesha turned east toward Lake Michigan for relief.

Local environmental organizations hired the engineering firm GZA GeoEnvironmental to look at alternatives to a Lake Michigan diversion, including solutions neighboring communities employed to mitigate radium contaminated drinking water. GZA took into account not only Waukesha’s trouble with radium, but also their concern that it did not have enough water capacity in their existing wells to meet the current and future needs of citizens and industry.[24] One solution that GZA analyzed was a treatment system called “Water Remediation Technology (WRT) Z-88.” Neighboring Wisconsin cities of Brookfield and Pewaukee, as well as six municipalities in Illinois and six additional American cities, use WRT.[25] GZA opines that this system, in addition to digging two new wells to replace ones that Waukesha has already or plans to shut down soon, can solve all of Waukesha’s water supply challenges for half the cost of diverting water from Lake Michigan. The current estimated cost of a diversion is $334 million.[26] Waukesha did not consider including different treatment alternatives, such as WRT, as part of the alternative options in its application for diversion. Instead, each of the options was a different source of water or combination of sources.[27]

After more than a decade, Waukesha approaches a quickly looming EPA 2018 deadline to bring its public water supply system into year-round compliance. Now that its application for a diversion from the Great Lakes has been approved, Waukesha is able to move forward with its preferred solution of a diversion. In accordance with the rules set forth by the Compact, Waukesha must return the water it borrows to Lake Michigan. The route they have chosen for this return flow is the Root River, which is where our environmental justice analysis is focused.

Environmental Justice Considerations of Waukesha’s Return Flow Plan via the Root River

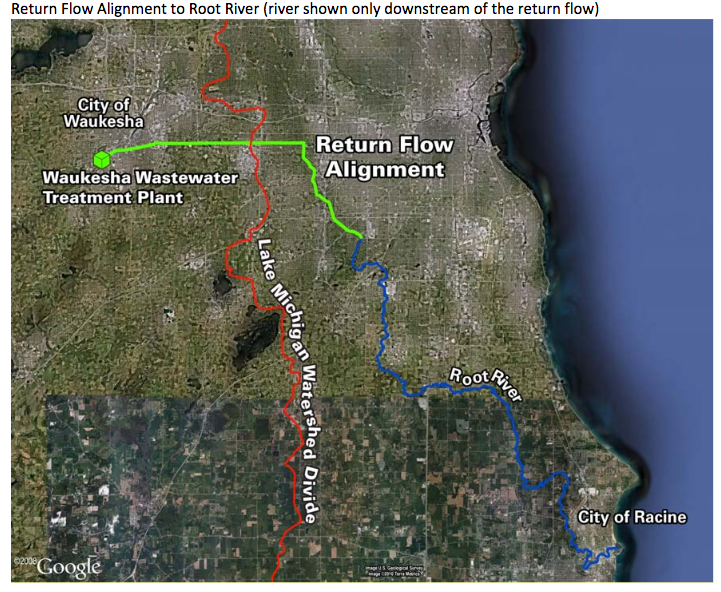

The Root River flows southeast from New Berlin through the community of Racine before flowing into Lake Michigan. While treated wastewater discharging into a river can present challenges to any community through which the river flows, there are several features of the community of Racine and the Root River Basin that make Waukesha’s decision to return its wastewater via the Root River, as opposed to Underwood Creek, uniquely concerning from an environmental justice standpoint.

In 2016, the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact Council (“Compact Council”) granted a diversion of water from Lake Michigan to the City of Waukesha despite strenuous objections based on social and environmental justice grounds advanced by the ACLU of Wisconsin, the Sierra Club, the Milwaukee Inner City Congregations Allied for Hope, and the NAACP-Milwaukee Branch. These organizations argued that granting a diversion would contribute to Waukesha’s unchecked suburban sprawl to the detriment of communities of color residing in the City of Milwaukee who historically have lacked access to jobs and housing in Waukesha. The State of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources endorsed the diversion application. Shortly after the Compact Council granted the diversion, the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative (“Cities Initiative”) filed a petition asking the Compact Council to review the decision. In support of the review request, the Cities Initiative offered several reasons why the diversion should not have been granted or, in the alternative, should be modified. However, none of these reasons touched on environmental justice considerations. After reviewing briefs by the Cities Initiative and the City of Waukesha, and hearing oral arguments, the Compact Council unanimously denied the Cities Initiative’s request to reopen or modify the decision to grant the diversion.

While these environmental justice objections are not insignificant to a broader analysis of whether a diversion should be granted, because the Compact Council granted the diversion, the next most pressing environmental justice consideration surrounds the selection of the river through which Waukesha’s treated wastewater effluent will be returned to Lake Michigan, i.e., its “return flow plan.” As stated above, the current plan provides that Waukesha’s treated wastewater will be returned to Lake Michigan via the Root River, which flows through the City of Racine, and not through the City of Wauwatosa via the Underwood Creek, as initially proposed. The communities of Wauwatosa and Racine are very different, such that an analysis of the decision to route the return flow through Racine, through the dimensions of environmental justice, is appropriate. The return of Waukesha’s treated wastewater via either river imposes significant environmental and economic risks to the surrounding community.

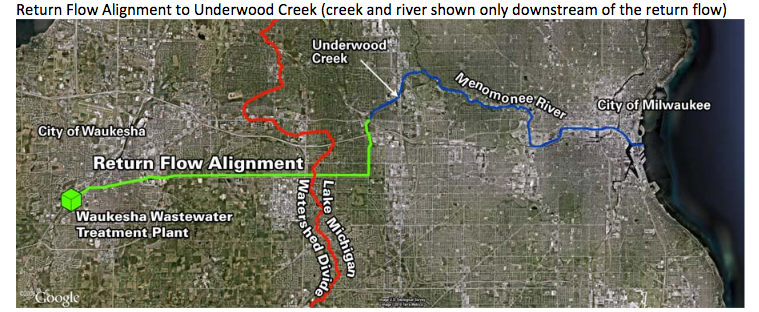

In May 2010, Waukesha initially committed to return 100 percent of Lake Michigan water (minus consumptive use) to Lake Michigan via Underwood Creek, which flows into the Menomonee River through the City of Wauwatosa near West Bluemound Road. However, after strenuous objections by the City of Wauwatosa, Waukesha amended its application and requested that its effluent be discharged back to Lake Michigan via the Root River. The effluent will be treated at the City of Waukesha sewerage treatment plant prior to discharge into the Root River. The proposed discharge point along the Root River is planned for at S. 60th St. in Franklin. Water treatment will include removal of chemical phosphorus, chloride, suspended solids, and organic materials; tertiary filtration; and ultraviolet light disinfection. The proposed phosphorus limits are below the water quality standard for the Root River. The City of Waukesha will be returning up to ten million gallons of treated effluent per day into the Root River. Based on prior review of Waukesha’s plan by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the Compact Council, the proposed quality of wastewater returned via the Root River by Waukesha will meet federal and state requirements.

In denying the Cities Initiative petition for review, the Compact Council concluded that the Cities Initiative failed to detail how the return flow, which must comply with federal and state water quality standards, would result in significant impacts on the basin, which is the standard of review required in the Compact. The Council’s conclusion seemingly ignores the scientists at UWM School of Freshwater Science and the City of Racine Dept. of Public Health, who have opined that there will be adverse environmental impacts on the Root River. While there are meaningful concerns about water quantity impacts to the Root River (flooding, erosion, sediment mixing), the most significant issue presented by the return flow plan relates to water quality. Specifically, the concentration of pathogens, pharmaceuticals, and other emerging contaminants that are not currently regulated and not treated via sewerage treatment facilities, will have a negative impact on the Root River. In addition, there are valid concerns about Waukesha’s ability to meet the proposed phosphorus and chloride standards, and Waukesha’s lack of financial liability for any negative impact for its failure to do so.

The WDNR identified elevated phosphorus and chloride levels in their Environmental Impact Statement and Technical Review of Waukesha’s diversion plan.[28] According to federal and state standards, discharge into the Root River cannot exceed a phosphorous standard of 0.075 mg/L or a chloride limit of 400 mg/L. Waukesha’s discharge will be permitted (through the Wisconsin Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) and required to meet these standards. However, reports compiled by the WDNR provide that Waukesha cannot meet the recommended chloride limit of 400 mg/L. In addition, consultants for Waukesha stated that Waukesha will not be able to meet the phosphorus standards consistently.[29] Excess phosphorus is a concern because it can speed up the process of eutrophication in a body of water, which in turn decreases ecosystem productivity. The inability to meet phosphorus standards consistently presents a significant challenge for downstream communities like the City of Racine. Furthermore, the Root River is already listed on Wisconsin’s Impaired Waters list as the upper sections of the river (the Root River canal and the West Branch of the canal) currently have excessive phosphorus levels, decreasing dissolved oxygen levels below what is necessary to support aquatic life.[30] Additional phosphorus inputs into the ecosystem will only exacerbate eutrophic conditions and increase the difficulty of implementing a remediation plan or Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for the waterway.

In addition to increased nutrient and chloride levels within the Root River, Waukesha’s discharge increases the likelihood of additional pathogens being introduced to the river. While Waukesha’s return flow will meet state wastewater treatment effluent standards, there is still the potential for pathogens to persist beyond the wastewater treatment process. Wisconsin wastewater effluent standards are partially regulated using total coliform counts and fecal coliform counts, known as bacterial indicators.[31] Bacterial indicators are conventional for wastewater treatment standards, however, research over the past several decades has demonstrated that these indicators do not adequately reflect the pathogenic contamination of wastewater.[32] Total coliform and fecal coliform counts do not indicate the presence of other categories of pathogens that do not stem from fecal contamination. Further, pathogenic contamination does not always follow a proportional relationship to the level of indicator bacteria present in the water.[33] Pathogenic concentrations have the potential to be high in wastewater, despite meeting effluent fecal and total coliform standards, as pathogens can persist beyond the reduction and inactivation methods used in treatment centers. This presents an environmental and public health risk as surface water containing wastewater discharge may pass the bacterial indicator standard, yet still contain harmful pathogens.

Concerns Remain after Granting Waukesha’s Application for Diversion

Contrary to Waukesha’s contention and the opinion of the Compact Council, there are several significant concerns with Waukesha’s return flow plan. First, while the City of Waukesha contends that the return flow will benefit the Root River by adding volume during times of low flow, Waukesha fails to acknowledge that during times of low flow, seventy five to ninety percent of the water in the Root River will be “treated” wastewater effluent: effluent which has not been treated for residual pathogens, microplastics, pharmaceuticals or other emerging contaminants.[34] This increased level of contamination will pose human health risks as well as risks to the riparian ecosystem. Waukesha also contends that the increase in flow to the Root River will improve Great Lakes fisheries. Waukesha, however, fails to appreciate the presence of unregulated contaminants in the return flow that will cause harm to fish and other organisms, including the people that recreate in and around the Root River.

Second, Dr. Sandra McLellan, a research professor at the UWM School of Freshwater Science specializing in environmental health, argues that the Waukesha effluent will contain increased amounts of contaminants and nutrients: an increase in phosphorus loading, higher concentrations of chloride, higher concentrations of total suspended solids, pharmaceuticals, higher concentrations of residual pathogens, and other emerging contaminants like microplastics and personal care products.[35] The quantity of these contaminants, Dr. McLellan stated, will have a profound impact on the quality of water in the Root River (and the near shore area of Lake Michigan) on which people regularly kayak, boat, and fish. In addition to impacts on human health, it is believed that many of these contaminants will have a negative impact on the health of the aquatic ecosystem. For instance, scientists at the School of Freshwater Science, including Dr. Rebecca Klaper, are studying the impact the diabetes drug, metformin, is having on fish in Lake Michigan. Other studies are documenting the impact microplastics and microfibers are having on fish and other wildlife that consume these micro-contaminants. Neither the City of Waukesha nor the Compact Council meaningfully addressed concerns about emerging contaminants.

Another significant concern is whether Waukesha, after it sets high phosphorus and chloride standards in the WPDES permit in order to secure approval, will subsequently seek a variance arguing that it is not technically feasible to meet the limits in the permit. Nothing in the Compact Council’s decision prohibits Waukesha from seeking such a variance. Therefore, Waukesha’s unwillingness to recognize the concerns of the community through which it intends to send its wastewater effluent, will be compounded by further reducing the quality of the effluent with a subsequent variance.

In addition, there is no requirement that Waukesha monitor the Root River, pre- or post-diversion, for the emerging contaminants as previously outlined. Waukesha’s Water Utility contracted with the University of Wisconsin-Parkside to begin monitoring the Root River’s water quality and biological conditions, including fish health. However, the monitoring excludes analysis for emerging contaminants, e.g., residual pathogens, microplastics or any pharmaceuticals. Likewise, the post diversion monitoring required by the Compact Council (set for a minimum of ten years) does not include emerging contaminants. Therefore, key components for assessing the water quality of the Root River will not be monitored. As outlined by Dr. McLellan, monitoring only for certain contaminants, such as E. coli and phosphorus but not residual pathogens, does not provide an accurate or comprehensive assessment of water quality.[36]

Furthermore, without accurate data, it will be difficult to assess whether the City of Waukesha’s return flow has a negative impact, significant or otherwise, on the Root River. The Compact Council did give passing reference to the concern about emerging contaminants by pointing out that it did require the City of Waukesha to develop a comprehensive pharmaceutical and personal care products recycling program, to reduce the quantity of these products entering the City of Waukesha’s wastewater, but the Council stopped short of requiring the City of Waukesha to monitor for contaminants not otherwise required to be monitored by federal or state law. Lastly, Waukesha is not required by the Compact Council to pay for any negative local, regional, or cumulative impact caused by its return flow. If the return flow does have a negative impact on human health, fisheries, or aquatic life, there is no provision in Waukesha’s plan to pay for the damage, leaving the City of Racine to bear the economic burden.

In light of the considerations outlined above, it is clear why the City of Wauwatosa vigorously objected to Waukesha’s initial plan to discharge its treated sewage via Underwood Creek (Figure Four). Clearly, the community of Wauwatosa understood that Waukesha’s plan to distribute its wastewater effluent was not as simple or “clean” as alleged by Waukesha in its return flow plan. What is unclear is what motivated Waukesha to amend its diversion plan, to request that its treated wastewater be discharged through the community of Racine via the Root River instead of through Wauwatosa via Underwood Creek, especially since it costs less and crosses fewer streams than discharging to the Root River. According to Waukesha’s 2010 application, the return flow through Underwood Creek had the lowest estimated capital cost of $56M with an annual operations and maintenance cost of about $120,000, as compared to the estimated costs for return flow via the Root River which were about $76M with an annual operating and maintenance cost of $145,000.[37]

Figure 4: Maps Showing Return Flow Paths Through Underwood Creek and the Root River

A Tale of Two Communities

As mentioned above, the demographics of Racine and Wauwatosa are distinct. According to the latest demographic information from July 2016, the overwhelming majority of Wauwatosa residents are employed (seventy-one percent) and enjoy a median household income of $70,000 with a median property value of $220,000.[38] By contrast, the median value of a home in Racine is $110,000, the median household income is $41,000, and sixty-four percent are employed with twenty-two percent living in poverty, as seen in Figure Five.[39]

| 2016 | Wauwatosa | Racine |

| Population: | 47,000 | 77,000 |

| High School Graduates | 97% | 82% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher: | 60% | 18% |

| Employed: | 71% | 64% |

| Median Household Income: | $70,000 | $41,000 |

| Persons in Poverty: | 6.30% | 22% |

| Median Property Value: | $220,000 | $110,000 |

| Home Ownership: | 63% | 52% |

| Caucasian: | 87% | 52% |

Figure 5: Wauwatosa and Racine Census Information Comparison (United States Census Bureau, 2017)

The last few miles of the Root River through the City of Racine includes popular fishing spots and an area that the City plans to revitalize. The City is working with developers on a sixty-five million dollar plan to redevelop an aged steam engine plant along the Root River waterfront as a mixed-use building with apartments and retail shops. In addition, the City spent the last fifteen years cleaning up North Beach. Racine officials and residents voiced concerns about the viability of these projects and the continued clean-up of North Beach to Waukesha’s planners, only to have them be rebuffed. The City of Waukesha rejects any concern by saying that the treated wastewater will be clean and that it will comply with all Federal and State laws. However as outlined above, the Federal and State standards do not adequately address issues of water quality like viruses and pharmaceuticals. In summary, Waukesha went from sending its treated wastewater through a middle class, predominantly White community, to discharging its treated effluent through an economically depressed community with a much higher population of minority residents.

Waukesha Planners Failed to Recognize the Concerns of the Community of Racine When Selecting a Route

Waukesha’s decision to change return flow routes after the citizens of Wauwatosa objected, failed to recognize and value the concerns of the citizens of Racine to the same degree that it did the citizens of Wauwatosa. Waukesha fails to recognize the concerns of Racine in repeating the pat response that the return flow effluent will be in compliance with state and federal laws, ignoring their concerns about other contaminants and potential negative economic impact. The City of Waukesha maintains a website dedicated to its diversion plan but the website does not include any information about the environmental justice implications of its return flow plan on Racine.[40] While there is a section about “myth” and “facts,” none of the sections include a response to Racine’s concern that its citizens will be fishing and swimming in Waukesha’s wastewater. In addition to a lack of recognition, the citizens of Racine have not been provided the opportunity to participate meaningfully in the process of selecting a return flow route.

Over the past several years that Waukesha planned its diversion and return flow routes, Waukesha and the WDNR held only one meeting in Racine. It is possible that the City of Racine officials held meetings and that possibly some residents of Racine travelled to a meeting outside Racine or submitted an online comment, however, the fact remains that Racine residents have not been afforded the chance to participate meaningfully in the planning process. On March 23, 2018, the Waukesha Water Utility submitted to the WDNR its 3-140 D2 Waukesha Great Lakes Water Supply Program WDNR Supplemental Environmental Impact Report-Redacted (SEIR). According to the SEIR, the WDNR conducted several meetings with affected communities, including two sets of public hearings and two public comment periods prior to submitting the Lake Michigan Diversion Application to the Compact Council in January 2016. The WDNR held three public “scoping” meetings on July 26, 27, and 28,2011, in Pewaukee, Wauwatosa, and Sturtevant. The WDNR prepared a draft Environmental Impact Statement and invited the public to comment on it between June 25 and August 28, 2015. Comments were also received at three public hearings on August 17 and 18, 2015, in Waukesha, Milwaukee, and Racine. Meaningful efforts at recognition and participation would include holding more meetings with the residents of Racine to discuss their concerns, allowing a representative from Racine to participate in the decision-making process, and being amenable to offering solutions to Racine’s concerns about water quality and economic impacts. Waukesha would like people to empathize and support their quest for a sustainable source of drinking water but seem reluctant to recognize and validate the concerns of other communities affected by that quest.

Waukesha has the opportunity to improve its image and its return flow plan by addressing the environmental justice implications its plans have on the Racine community. Figure Six shows some potential points of interjection in the DSRP map created for this analysis. The WDNR can collaborate with Waukesha, Milwaukee, and Racine, and facilitate discussions about potential economic and environmental impacts from the diversion. The discussions can then be used by the WDNR to create stronger regulations that should not be a problem for Waukesha adherence. Further discussions will make Waukesha a stronger participant in monitoring the Root River as regulations are adapted to the new terms. Additional groups, such as the UWM School of Freshwater Science and the City of Racine Dept. of Public Health, will be included as consultants in creating new regulations, establishing a collaborative monitoring and remediation program, and experimenting with filtration methods. One concern over the treated wastewater is the additional input of emerging contaminants and residual pathogens. Waukesha can fix this concern by becoming a test candidate for new filtration technologies created to filter emerging contaminants. New regulations and standards can strongly motivate the research and development of new filtering methods. In addition, Waukesha should consider setting up a fund to help Racine pay for the damages likely to be caused by flooding and erosion resulting from the increased flow rate in the Root River. By taking these steps, Waukesha could become a model city for requesting and accomplishing the first major diversion that challenged the Great Lakes Compact, the very document created to prevent transfers outside of the basin.

Figure 6: DSRP/Systems Thinking Map with Potential Interjection Points

Figure 6: DSRP/Systems Thinking Map with Potential Interjection Points

It can be presumed that the Waukesha diversion is the first of many subsequent diversion proposals to be pursued within the Great Lakes Basin. To begin considering any future diversions similar to Waukesha, the current diversion case needs to set strict standards and regulations to follow in order to prevent any environmental injustice and economic impact. Of course, this is dependent on the success a new application has in getting approved to move forward with a proposal. Such decisions can benefit immensely by the inclusion of local residents, private entities, and government authorities, in deciding the fate of a new application. A pragmatic approach to these decisions can provide economic prosperity without the loss of environmental benefits or public safety. The Waukesha diversion will need a workforce for its construction, and big projects like this one can generate needed jobs. Milwaukee is currently in a position of requesting jobs for its residents, for construction of the infrastructure. The employment can be extended by establishing maintenance and monitoring protocols. Similar opportunities can be created in potential future diversion projects should they be considered.

Conclusion

As outlined above, there is no question that Waukesha’s plan to return its wastewater to Lake Michigan via the Root River will introduce unregulated contaminants to the river and lake which will cause harm to those ecosystems and people who rely on them for drinking water, sustenance fishing, and recreation. It can be argued that Waukesha’s plan to return the water used by its majority White, affluent residents, via a river that flows through a predominantly non-White, working class town, unfairly distributes health and economic risks to the City of Racine. In response, Waukesha’s statement that its wastewater discharge will meet federal regulations rings hollow. In addition, Racine residents may lose access to the river, and local businesses dependent on the river may see a drop in customers and profit.[41] These are all potential burdens suffered by Racine without any attendant benefits. The burden imposed on Racine residents will not be shared by the residents of Waukesha, as there is no requirement by the Compact Agreement or the WDNR approval that the City of Waukesha pay for any economic or ecological damage caused by the return flow. While Waukesha has already gained the permission it needs to divert water from the Great Lakes Basin, the plan to return the water via the Root River has not been finalized. In light of these serious concerns regarding the injustices imposed on the Racine community, it is recommend that Waukesha either select a different return flow route, or make a financial commitment to assist Racine in mitigating and/or remediating any damage caused by flooding or erosion. At a minimum, the WDNR should require the City of Waukesha to devise a plan that reduces the amount of contaminants sent to the water treatment facility, and require the sewage treatment facility to improve wastewater treatment and testing systems to reduce the amount of microplastics, pharmaceuticals, and other unregulated contaminants being discharged to the Root River.

References

- Great Lakes- St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Council, “Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact,” December 2005, 1 – 27. ↑

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, “New Hope for Wicked Problems,” in Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems, (USA: Plectica Publishing, 2015), 12-20. ↑

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, “New Hope for Wicked Problems,” in Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems, (USA: Plectica Publishing, 2015), 12-20. ↑

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, “New Hope for Wicked Problems,” in Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems, (USA: Plectica Publishing, 2015), 12-20. ↑

- David Schlosberg, “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories,” Environmental Politics 13, no. 3. (2004): 517- 540. ↑

- David Schlosberg, “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories,” Environmental Politics 13, no. 3. (2004): 517- 540. ↑

- Dalia Saad, Deirdre Byrne, and Pay Drechsel, “Social Perspectives on the Effective Management of Wastewater,” Physico-Chemical Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery. (April 2016): 253- 262.↑

- Jill E. Johnson, Emily Werder, and Daniel Sebastian, “Wastewater Disposal Wells, Fracking and Environmental Injustice in Sourthern Texas,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 3. (March 2016): 550-556. ↑

- Jill E. Johnson, Emily Werder, and Daniel Sebastian, “Wastewater Disposal Wells, Fracking and Environmental Injustice in Sourthern Texas,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 3. (March 2016): 550-556. ↑

- David Schlosberg, “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories,” Environmental Politics 13, no. 3. (2004): 517- 540. ↑

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, “Great Lakes Compact Background,” 2018. ↑

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, “Great Lakes Compact Background,” 2018. ↑

- Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- Great Lakes- St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Council, “Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact,” December 2005, 1 – 27. ↑

- United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” July 2017. Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” July 2017. ↑

- United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” July 2017. ↑

- Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- Ben Merriman, “Testing the Great Lakes Compact: Administrative Politics and the Challenge of Environmental Adaptation,” Politics and Society, 45 no. 3. (June 2017): 441- 466. ↑

- Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- Ben Merriman, “Testing the Great Lakes Compact: Administrative Politics and the Challenge of Environmental Adaptation,” Politics and Society, 45 no. 3. (June 2017): 441- 466. ↑

- Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- GZA GeoEnvironmental Inc, “Response to Comments on Non-Diversion Alternative,” February 2016, 2-11. ↑

- GZA GeoEnvironmental Inc, “Response to Comments on Non-Diversion Alternative,” February 2016, 2-11. ↑

- GZA GeoEnvironmental Inc, “Response to Comments on Non-Diversion Alternative,” February 2016, 2-11. ↑

- Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, “Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative Reply to City of Waukesha’s Response to The Cities Initiative Request for a Hearing,” February 2017, 1-34. ↑

- Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, “Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative Reply to City of Waukesha’s Response to The Cities Initiative Request for a Hearing,” February 2017, 1-34. ↑

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, “303(d) Impaired Waters List,” 2018. ↑

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, “Wastewater Regulations,” 2018. ↑

- Valerie J. Harwood, Christopher Staley, Brian D. Badgley, Kim Borges, and Asja Korajkic, “Microbial source tracking markers for detection of fecal contamination in environmental waters: relationships between pathogens and human health outcomes,” FEMS Microbiology Reviews 38, no 1. (January 2014): 1- 40. ↑

- Valerie J. Harwood, Christopher Staley, Brian D. Badgley, Kim Borges, and Asja Korajkic, “Microbial source tracking markers for detection of fecal contamination in environmental waters: relationships between pathogens and human health outcomes,” FEMS Microbiology Reviews 38, no 1. (January 2014): 1- 40. ↑

- Sandra McLellan, “Microbial Indicators” (class lecture, Water Law for Scientists and Policy Makers, UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, October 25, 2017). ↑

- Sandra McLellan, “Microbial Indicators” (class lecture, Water Law for Scientists and Policy Makers, UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, October 25, 2017). ↑

- Sandra McLellan, “Microbial Indicators” (class lecture, Water Law for Scientists and Policy Makers, UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, October 25, 2017). ↑

- Ch2mHill, “Application Summary: City of Waukesha Application for a Lake Michigan Diversion with Return Flow,” October 2013, Volume 1: 1.1 – 5.1. ↑

- United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” July 2017. ↑

- United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” July 2017. ↑

- Waukesha Water Utility, “Myths and Facts about Waukesha’s New Water Supply Program,” 2016. ↑

-

Wasim Ahmad and Marwan Ghanem, “Enhancing of Socio-economical Environmental Impact of the Wastewater Flow on Communal Level,” International Journal of Research In Social Sciences 6, no. 2 (January 2016): 46- 52. ↑