Abstract:

This paper utilizes the DSRP principles of systems thinking to explore the role of workforce development in city economic competitiveness. A city’s economic competitiveness is vital, not only for attracting new businesses but also for ensuring the survival of current businesses. Ideally, an economically competitive city enables its firms to compete in their markets and create wealth that is shared among its citizens, leading to a high quality of life. This paper’s analysis develops a better understanding of the tools available to policymakers to support local businesses, and how the behavior of different actors can compromise cities’ abilities to maintain or enhance their competitiveness and their tax revenues. It finds that actors’ impacts on business create feedback loop effects such that changes in one actor’s contribution to economic development impacts another actor’s ability to support development. The analysis shows that workforce development policies are an important component of competitiveness, and cities’ non-involvement in workforce intermediaries and employment centers, which are safety nets for the workforce development system, sets their welfare and economic development at risk. Applying DSRP principles led to the discovery of these unique feedback effects and the internal relationships between the economic development system and business needs; in a conventional policy analysis, these effects would have been overlooked as it often ignores the inter-system relationships and the perspectives of policy actors.

Introduction

Systems thinking teaches learners to think in a way that enables them to appreciate the small nuances of an issue, as well as how small facets of a problem fit into larger systems and relationships. systems thinking is particularly useful in exploring how a city’s public policies can affect workplace development and impact competitiveness (i.e. a city’s competitiveness in attracting businesses and the ability of businesses to compete in their respective markets).

Exploring this topic was prompted through prior research. Specifically, studies show that local economic development specialists tend to think of workforce development as “social work,” rather than economic development work.[1] In addition, through my own research I discovered that the top 20 largest cities in the U.S. do not have a governmental department or agency that is tasked with addressing workforce development issues. Both of these facts are perplexing, as the labor market has an evident impact on economic growth and prosperity. But is bias against workforce development a problem? What about the lack of involvement in workforce development by major U.S. cities? What about when these questions are placed in the context of improving a city’s economic competitiveness and its attraction of businesses? To answer these questions, one has to understand how workforce development fits into economic development as a whole, and which various actors are involved in this development process. Utilizing systems thinking to answer these questions clarifies the facets of the economic development system and how that system relates to business competitiveness and success.

Applying DSRP Systems Thinking Principles: Determining the Basic Elements of the Systems in Question

Systems thinking has four rules that guide how to think about things and ideas. These rules are captured in the acronym DSRP: Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives. The Distinctions Rule indicates that any thing or idea can be distinguished from others. It prompts us to critically consider what our concepts are or are not—and how we define those boundaries. The Systems Rule states that every idea or thing can be split into constituent parts and is also a part of a greater whole—of a greater system of parts. The Relationship Rule explains that every thing or idea can be related to other things or ideas; these relationships can be of any type, causal or otherwise. Finally, the Perspective Rule states that any idea or thing can be a “point” or “view.” In other words, each idea or thing is a lens through which one can view other ideas or things. These DSRP principles are the foundation of this paper’s analysis; they were used to determine business needs and the systems that address those needs.

Business Needs and the Systems that Address Them

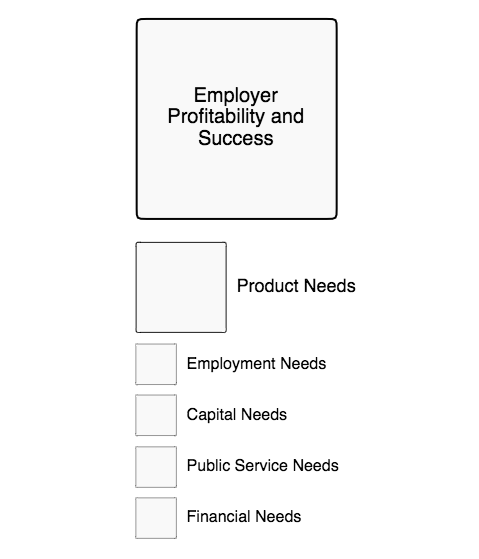

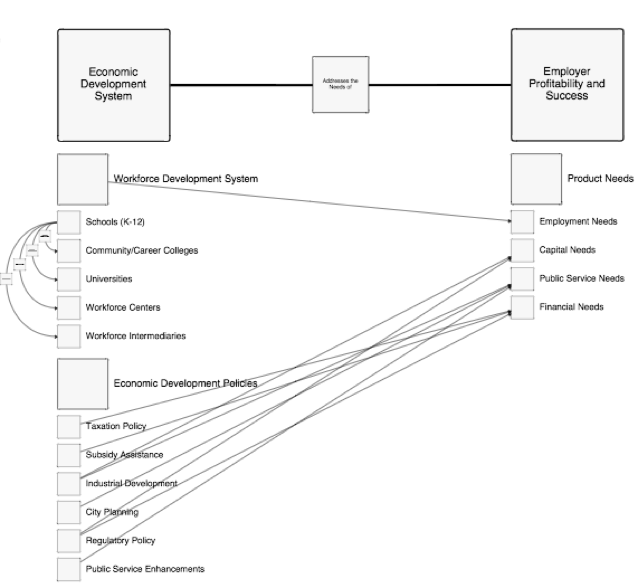

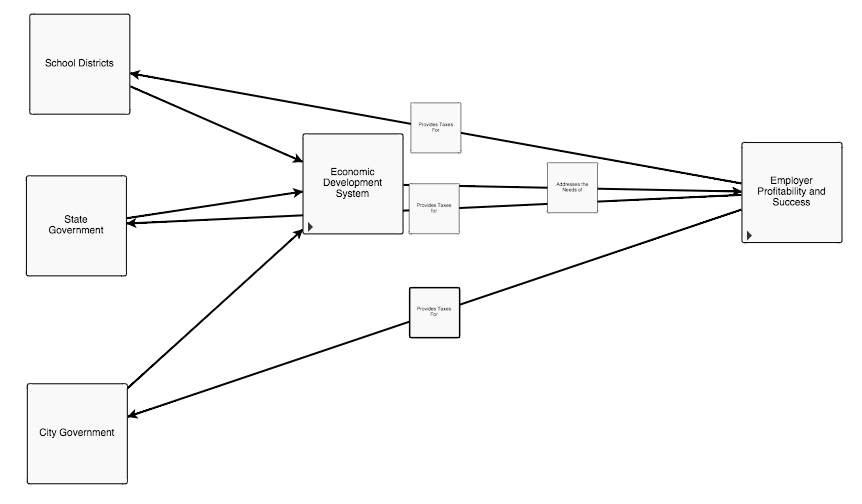

This analysis began with thinking about the needs of businesses and the systems available to address these needs. I posit that meeting business needs will lead to business success. Presumably if a business could be most successful in a city, it would want to remain there. If a foreign business would be better off in that city, capable of achieving higher business success, there would be an incentive for that business to move there. The primary component of business success is product success in a given marketplace.[2] Product success is contingent on four separate needs: employment needs (such as skilled workers), capital needs (machinery and factories), public service needs (utility services and functioning roads), and financial needs (the day-to-day availability of cash to begin and sustain operations and meeting tax obligations). While these needs are interconnected—for example, meeting financial needs allows the purchasing of capital and employment—they are also distinct and separate, and they could be addressed individually. Together these needs form a larger system of business success shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Employer Needs System

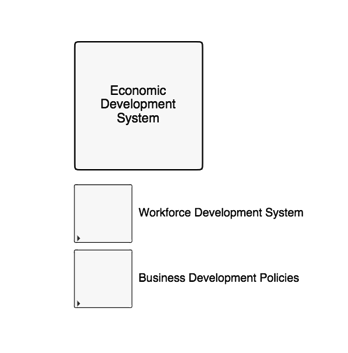

I then tried to conceptualize the system in place to address these needs. I called it the “economic development system,” and determined that it was comprised of two smaller systems of tools utilized by various actors to meet the needs of businesses. When determining the parts of this system, I established that there is the workforce development system, which works to produce skilled labor and conventional business development policies that support businesses directly through financial and service assistance. This economic development system is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Economic Development System

Figure 2: The Economic Development System

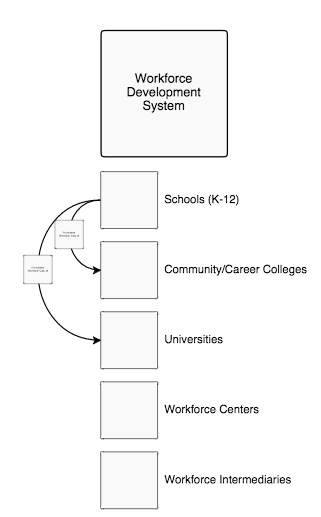

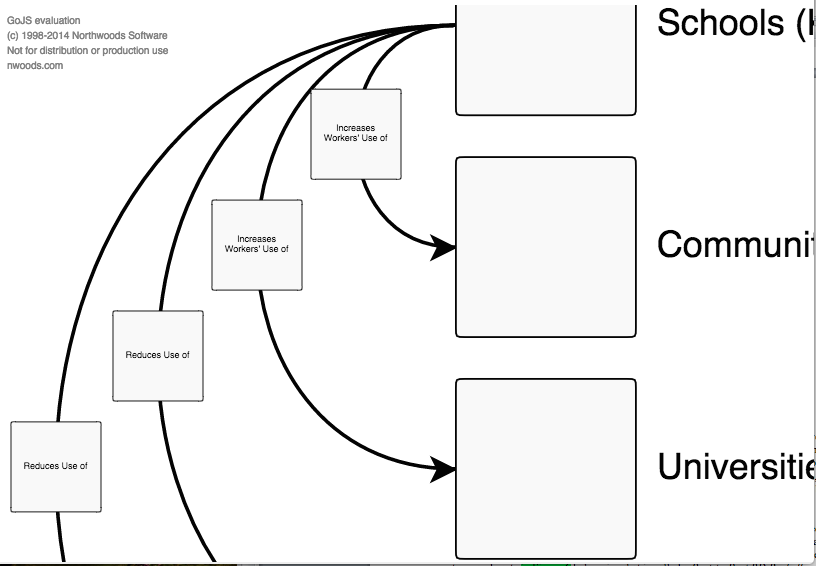

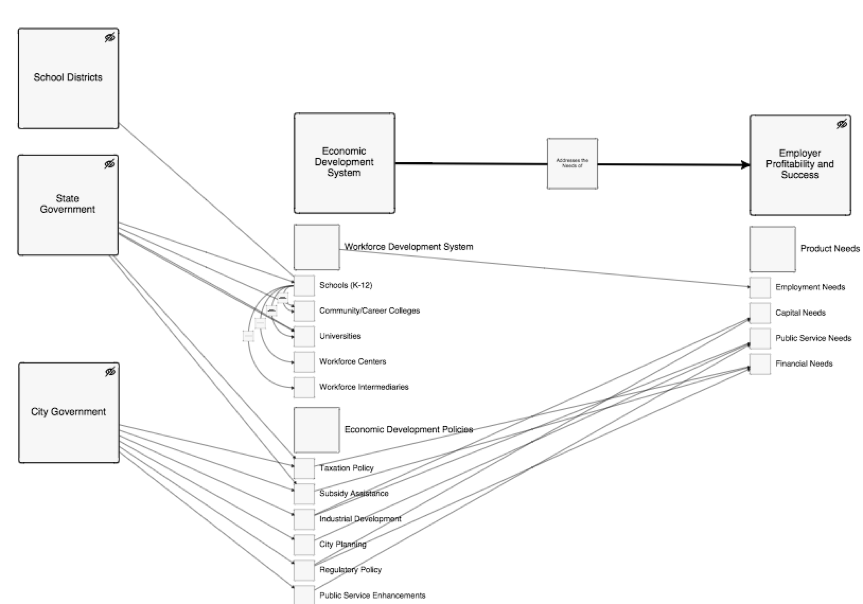

Within the workforce development system, scholars have identified a number of tools that contribute to meeting workforce needs. These include K-12th grade schools, community colleges and career colleges, and universities; organizations called “labor market intermediaries,” which set up specialized trainings and other services for workers; and workforce centers, which connect unemployed workers with employment matching assistance and training information to improve their chances of employment. The relationships among these components of the workforce development system are thus very important. Presumably, if the K-12 educational institutions do well in preparing students for further education, students will go on to community or career colleges or universities to further their education. These positive relationships are mapped out in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Positive Relationships in Workforce Development System: Schools Positively Support Community/Career Colleges and Universities

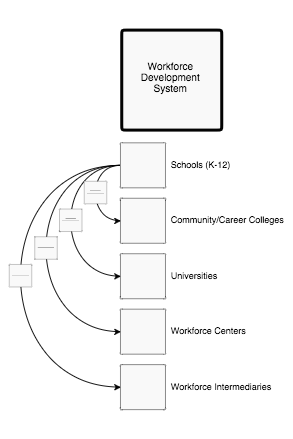

Further analysis of the role of workforce centers and workforce intermediaries shows that individuals who lack skills or cannot find employers in need of their skill sets are the primary users of workforce centers. These centers provide them matching services or identify training providers for the individuals to attain new skills. Intermediary organizations assist workers who struggle to attain skills due to problems such as impoverishment or mental or behavioral disabilities. They also serve individuals who do not have marketable skills. The usefulness of these organizations is inversely related to the functioning of the K-12 schooling system (see Figure 4 below): if the school system works well, fewer people will need workforce centers or intermediaries, generally speaking, but if it does poorly, these organizations have to conduct remedial work to help the population meet the skill needs of employers. These are some of the nuances that are uncovered by carefully defining the systems, parts, and their relationships when using a Systems thinking approach.

Figure 4: The Positive and Negative Relationships within the Workforce Development System (Close-Up at Bottom)

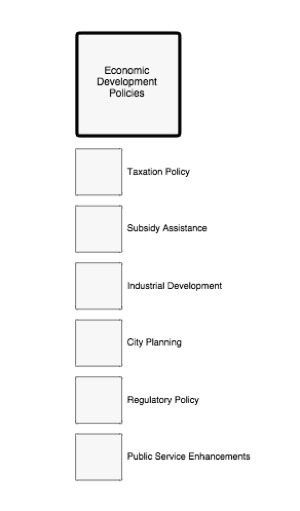

The workforce development system we have just examined, however, is only one part of the larger economic development system. The other part is the “economic development policies” system. This system includes policy tools such as direct subsidies, taxation policy (such as tax exemptions), industrial development (like building specialized infrastructure), city planning (for example, zoning changes), regulatory policies, and public service enhancements. Seen in Figure 5, these related yet distinct tools allow governments to assist businesses.

Figure 5: The Economic Development Policies System

When the economic development system and business needs systems are considered together, we can determine the relationships between the tools of development, such as schools and subsidies, and the business needs they address or support. I mapped these relationships between the two systems and parts in Figure 6 below, in what is called a Part-to-Part RD Barbell—a systems thinking tool that relates two systems parts to one another.

Figure 6: The Economic Development System and Business Needs System Part-to-Part RD Barbell

The relationships indicated in the barbell illustrate how the Economic Development System helps address the needs of businesses, as all the components on the left address one or more of business need-components shown on the right. In these systems, if all or some of the Economic Development System tools were used, the needs of businesses in a locality would be met. (For example, even if a city does not provide subsidies for industries, reasonable tax policies might sufficiently meet a business’s financial needs). While a business does not need some of these services, such as a subsidy, to exist, cities use these tools to address business needs by fostering healthy competition, thereby attracting or retaining businesses that seek these policies to be more successful.

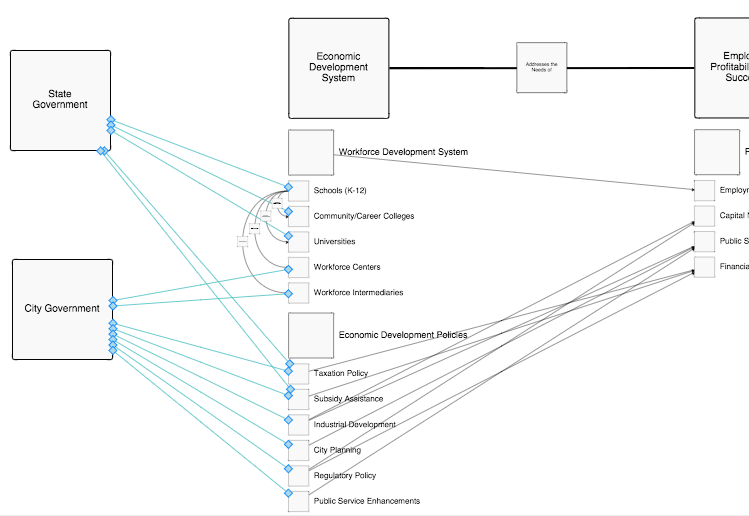

Introducing Actors and Perspectives: Complicating Factors in the Economic Development System

While System Thinking rules thus far have led to a meticulous understanding of the relationships described above, we must also explore the impact of “perspectives” (the “P” in DSRP) in the analysis. We will assume, for simplicity that our perceivers are the parties that are involved in economic development: the businesses themselves and government actors. I assume government actors to include city and state governments, because they are the most directly active in setting economic development policy. Cities control economic development policies in order to serve their businesses, and they can often impact workforce centers by providing funding, other assistance, or direction. They can also grant funding for intermediaries to serve city residents and businesses. States, on the other hand, are primarily involved with the labor market system through the funding of schools, colleges, and universities. In addition, they might engage in subsidy or tax policy adjustments that are beneficial to businesses. The relationships mapped below in Figure 7 indicate which actors generally use which tools.

Figure 7: Government Actors and Their Primary Policy Tools (Highlighted in Blue)

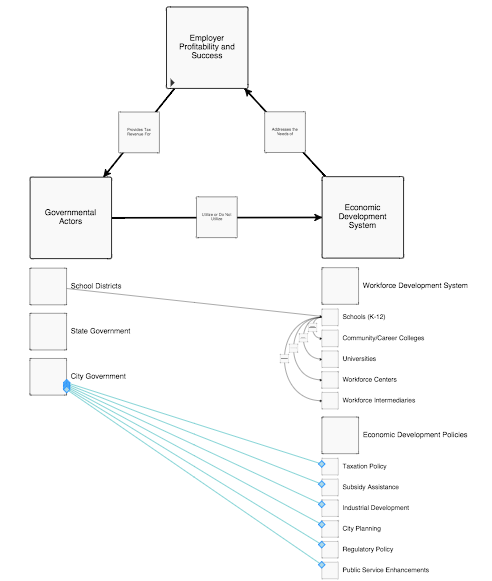

Although it may appear that the construction of the systems involved is now complete, as we know who uses the economic development systems and how these systems contribute to business success, some unexplored components of the system remain. Business success also contributes to the continuation of the system, a clear example of a feedback loop. A business will move to a city, or remain there, because that city (best) meets its competitive needs. This desirability to be in the competitive city fuels higher property taxes for schools, as the economic environment draws workers and businesses alike to the city demanding properties and driving up property values. Some of these property taxes go to a final actor we have yet to acknowledge—school districts, which fund the K-12 school system. This dynamic represents one important feedback loop. Business success also fuels the city and state’s resources by generating tax revenues (income taxes from workers and corporate taxes from businesses) that support states and cities, giving them funding to continue their involvement in economic development through programs and services. The feedback relationships between business success and these actors can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Feedback Loops between Employer Success and the Actors Involved in Economic Development

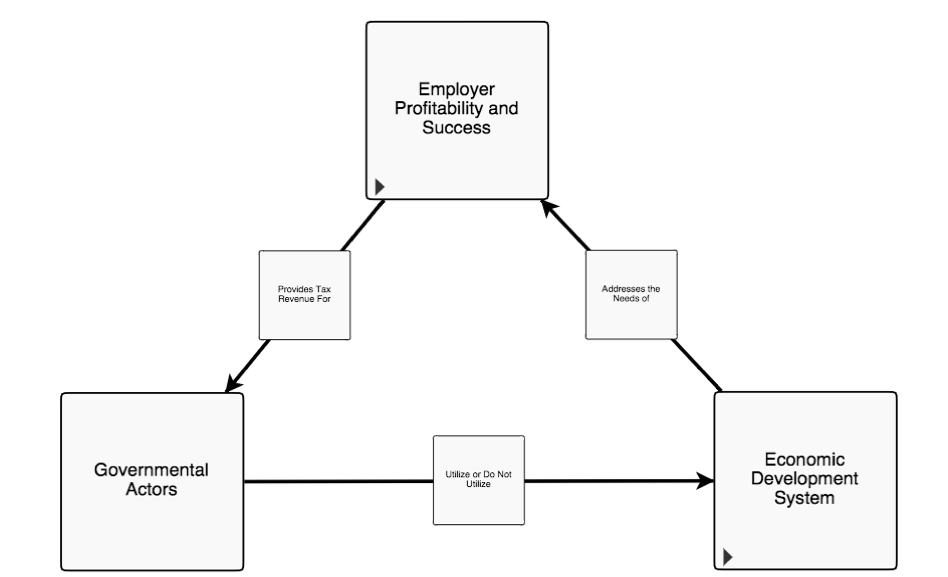

We can simplify the system above further to see more clearly the actors, the economic development system, and their impacts on business success: together, there is a clear feedback loop among these uncovered systems (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: The Feedback Loop among Actors, the Economic Development System, and Employer Success

However, Systems thinking tells us that this depiction is not quite complete, either. Perspectives are an integral part economic development and understanding them helps us to discover how this feedback loop, and city competitiveness, can be compromised. Among the government actors above, each perceives a role or responsibility in using the economic development tools at their disposal. Businesses perceive their potential success as factors of the development tools used (tax credits, reliable schools, etc.) and whether their needs are met. Particularly influential is the city’s bias against supporting workforce development tools, mentioned earlier, such as workforce intermediaries and employment centers: these organizations are often disparaged as types of welfare rather than economic development, despite their critical influence in the workforce development system if the K-12 schools, colleges, and universities do not function. In the scenario just described, cities might take a hands-off role in workforce development activities as a result of this bias.

The relationships between actors and the parts of the economic development system can be re-mapped when considering how perspectives affect the current interactions of these systems. In Figure 10a, cities are not involved with the workforce development system. Examining the relationships outlined in the diagram, it appears likely that individuals will need intermediaries or workforce center assistance to develop marketable skills, as the workforce development system increasingly requires remedial training or other assistance.

Figure 10a: Cities: Unengaged with Workforce Development

Without city involvement, business employment needs—a core component of business product success—will not be met. Businesses will thus perceive and experience a reduction in competitiveness. They may leave the city or do poorly, leading to a reduction in corporate or income taxes for the government, thereby reducing resources for all actors, impacting funding to use economic development tools in the future (such as schools or industrial development strategies), and impeding economic development. The feedback vulnerability can be seen in Figure 10b.

Figure 10b: Actors at Risk: Feedback Effects of an Unsupported Workforce Development System (City Economic Development Tools Highlighted in Blue)

Conclusion

Many cities lose sight of the feedback effects that their decisions can have on their businesses’ competitiveness. In particular, the bias against workforce development encourages cities to eschew workforce development policies and programs at their own peril. This systems-based examination of economic development has resulted in a more complete analysis of the role of workforce development in economic competitiveness.

The analysis linked business needs, the economic development system, and actors together using DSRP principles, thus revealing the feedback loops that fuel government involvement in economic development. As shown, city governments’ biases cause a lack of involvement in addressing workforce needs that raise the potential for negative feedback effects. Without a city being involved with workforce development, it is largely dependent on the decisions of other government actors to utilize the workforce development tools that are so critical to meeting business labor needs and promoting opportunity for residents. Schools play a big role in development. Cities can work to mitigate damage from the failures of the workforce development system by investing in workforce intermediaries and/or employment centers to assist workers failed by schools, thereby insulating them from the risk of long term harm to economic development. City involvement is a safety net for the workforce development system. By modeling how cities’ biased perspectives toward workforce development affects the economic development system, we can determine how small changes in an actor’s behavior can impact the entire system through feedback loop effects.

It is safe to say that cities’ current bias against participation with workforce intermediaries and employment centers puts city governments and other actors at risk of negative feedback effects. This assessment shows the usefulness of utilizing Systems thinking principles to better understand public policy predicaments and to disarm biases and misunderstandings that otherwise impede smart public policy decisions. These principles are particularly useful when trying to analyze policy problems that involve feedback effects, such as in economic development.

References

- Joan Fitzgerald, “Moving the Workforce Intermediary Agenda Forward,” Economic Development Quarterly 18 (2004): 3-9. ↑

- For the sake of simplicity, I decided to leave out a demand-side analysis. We will assume the businesses we are considering have markets for their products. ↑

About the Author: Derek Moretz is a graduate student at the Cornell Institute for Public Affairs, pursuing a Masters of Public Administration degree. He specializes in economic and financial policy and is interested in municipal governments’ roles in promoting economic development and the general welfare.

Derek, I feel that you are onto a critical topic. A dimension of the challenge that does not seem explicit in the model, is the feedback loop through which “critical-ity” of a role can be balanced with “effectiveness” of a role. For example, when you conclude “Cities can work to mitigate damage from the failures of the workforce development system by investing in workforce intermediaries …” one must have confidence that the specific intermediaries (like specific school districts) are doing the work that needs to be done. Can you model the responsibility for transparent communication into your model? The uncertainty, and the cost of becoming sufficiently less uncertain, represent a pragmatic bias in managing (local) investment risks. I suggest that when you do include consumers of workforce development work … the demand side (as you note) … you might discover deeper points for intervention in bridging training to employment. At the extreme, workers who are over-trained / over-qualified are also excluded from the workforce. I say this because without a transparent means of assessing the stranded assets in the already-trained workforce, we can train to replace a currently skilled workforce with newer, lower-wage substitutes. I suspect that these considerations are apt to be part of your next steps. You might consider asking the question “what are the critical elements that we need to have in an effective workforce development program?” and model these features using Interpretive Structural Modeling. The resulting model would show the flow of influence among essential elements, and this will aid in suggesting points for intervention.