On October 29, 2015, China scrapped its one-child policy, allowing all couples to have two children for the first time since strict family planning rules were introduced more than three decades ago. Despite the optimistic responses of some demographers and citizens on Chinese state media[1], the shift to the new two-child policy may disappoint those who expect the policy to lead to balanced population development and mitigation of China’s rapidly aging population.

China’s population increased by around 400 million from 1949 to 1976, influenced by the promotion of population growth during Chairman Mao Zedong’s era.[2] The Chinese government introduced its one-child policy in 1979, based on the conviction that strict population containment would prove essential to economic reforms aimed at improving standards of living.[3] Setting the goal of curtailing population growth to 1.2 billion by the year 2000, the National Population and Family Planning Commission was responsible for the implementation and regulation of population growth. The detailed implementation of the one-child policy varied at different times and places in China. Family-planning committees at provincial and county levels devised their own local one-child policy implementation plans. For urban residents and government employees, the one-child policy was strictly enforced with very few exceptions to allow more than one child per family. Exceptions included families in which the first child had a disability or both parents worked in high-risk occupations (such as mining) or were themselves from one-child families (in some areas).[4] In certain rural areas, a second child was actually allowed when the first child was a girl, reflecting cultural preference for male heirs.

This policy was supported through a system of rewards and penalties, including economic incentives for compliance and substantial fines, confiscation of belongings, and dismissal from work for noncompliance, especially for workers in the public sectors. More specifically, parents who had only one child would receive a “one child certificate,” entitling them to a variety of benefits. Parents were rewarded for having one child with “an extra month’s salary every year until the child turned 14, higher wages, interest-free loans, retirement funds, cheap fertilizer, better housing, better health care, and priority in school enrollment.”[5] However, if couples failed to comply with the policy, they could be fined “$370 to $12,800,” an amount many times the average annual income of many Chinese. If the couple was unable to pay the fine, they might lose their jobs, have their land and livestock confiscated, have their home destroyed, have their children denied the rights and benefits of the state (like education), or face having their child taken away. Women could also be forced to be sterilized.[6]

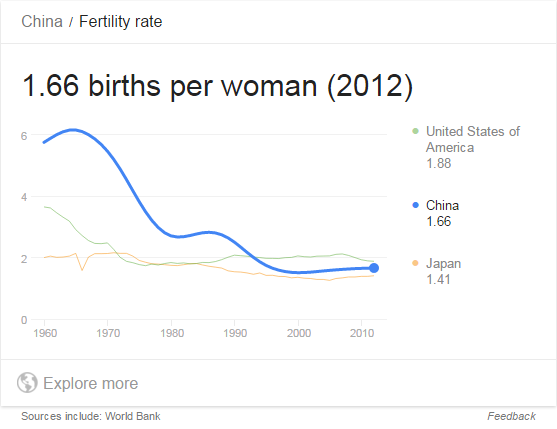

The one-child policy has been controversial since its introduction. A UN Population Division (UNPD) study estimates the Chinese total fertility rate (TFR) at roughly 1.55 births per woman.[7] China’s coercive family planning policy arguably has accelerated the decline of the country’s fertility rate. The government has also claimed that reducing the TFR has prevented 400 million births while simultaneously lifting 300 million people out of poverty.[8] Though research has not been able to prove the inverse relationship between fertility and per capita income, evidence from many developing countries tends to validate the relationship.[9] The fall of the TFR may also be associate with a rise in women’s education level. Women now account for 52% of undergraduates and 48% of postgraduates.

However, it is not clear to what extent the declined TFR and the rise of female education level directly led to the one-child policy. The most dramatic population decrease happened even before the policy was introduced (Figure 1). Countries like the US and Japan also have showed decreases in fertility rates without the one-child policy.

Figure 1

While China’s low population growth in recent years is impressive, the bold one-child policy has also had considerable negative consequences, including a sex ratio imbalance, an aging population, a declining workforce, and what some may call personality disorders for those who are the single child in their families. These effects will be felt for years to come.

Although it is illegal to use ultrasound to identify fetal sex in China, this practice is still widely popular. While the one-child policy was in effect, many families chose gender-based abortion to ensure that their one child was a boy. These practices, along with infanticide, have created a serious sex imbalance, and have resulted in a 1.16 male over female ratio. The significant gender disparity in China (with as many as 30 million women “missing”) contributes to, among other things, increased rates of depression among single men, as well as increased rates of kidnapping, trafficking of women for marriage, and commercial sex work, which increases the risk of spreading sexually transmitted diseases.[10]

Together with extended life expectancy, the large number of people born during Mao’s baby boom era has lead to a rapid aging of China’s population. Due to the lack of a comprehensive social security system, older people in China significantly depend on their children to support them when they grow old. When members of the “one-child generation” enter the work market, each individual is often responsible for providing support for his or her two parents and four grandparents, especially when the older generations do not receive retirement funds. This imbalance is the so-called 4:2:1 phenomenon. Naturally, these factors have created a huge financial burden for the one-child generation.

Besides the familial pressures at the individual level, China is now confronting the possibility of growing old before growing rich. Projected to have nearly 300 million people over the age of 65 by 2035, China is surpassing the aging pace of Japan, while China owns one third the purchasing power parity of Japan’s GDP per capita. As one of the main engines of global growth over the past decade, China’s annual GDP growth slowed to 6.9 percent in 2015 compared to 10.6 percent growth in 2010. China is now making a tough shift to relying more on consumer spending and services, rather than prioritizing manufacturing and infrastructure spending. With a declining working-age population who are the primary buyers of good and services, China still has a long way to go to achieve sustainable and long-term economic growth.

Despite its optimism that the newly implemented two-child policy can result in healthy economic development, China’s government may not get the population increase it expects. When the one-child policy was relaxed in 2013, for example, allowing couples to have two children if one parent was an only child, the outcome was far from what had been predicted. Despite the prediction that between 10 to 20 million couples were eligible for this relaxed version of the policy, less than 1.5 million couples had taken advantage of the allowance as of May 2015. According to data from the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Survey, 35 percent of the women questioned preferred having only one child and 57 percent preferred having two children. The financial burden is likely their main concern, since the cost of raising a child in China is very high. In large cities like Beijing and Shanghai, parents have to spend as much as 2 million yuan ($308,637) to raise a child to university age.[11] The annual average incomes in Beijing and Shanghai are 6776 yuan and 7362 yuan, respectively. One interviewee of the Wall Street Journal, Li Shuning explains, “For a second child, my answer is no, no, no. Doesn’t matter what the policy is.”[12] It is fair to estimate that China’s population growth may still be below the replacement fertility rate, which may become a bigger problem for China down the road. Without a decrease in educational and other child-rearing expenses or an increase in financial incentive support, well-educated generations will tend to have a muted reception of the new policy.[13] Changing the allowed number from one child to two still does not indicate that Chinese parents possess the right to freely determine their number of children. In this regard, the new family plan does not change the criticism that China’s reproductive policy violates human rights.[14]

Though time is needed to see how many new births will result from the latest policy change, the shift is not likely to have made a large difference. Rather than celebrating the symbolically loose restrictions on family planning, the Chinese government should instead emphasize the achievement of sustainable population development.

References

- http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-abandons-one-child-policy-1446116462 ↑

- A review of population theoretical research since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.popline.org/node/358793#sthash.fXAoBPIr.dpuf ↑

- Zhu WX, The one child family policy. Arch Dis Child 2003; 88:463-4 ↑

- Therese Hesketh, Lu li, and Weixing Zhu, The effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy after 25 years. The New England Journal of Medicine 2005; 353:1171-1176 ↑

- Hays, Jeffrey. “One-Child Policy in China.” Facts and Details. Ed. Jeffrey Hays. Jeffrey Hays, 2012. Web. 27 Jan. 2013. ↑

- http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat4/sub15/item128.html ↑

- http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/longrange2/WorldPop2300final.pdf ↑

- Wang JY. Evaluation of the fertility of Chinese women during 1990-2000. In: Theses collection of 2001 National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Survey. Beijing: China Population Publishing House, 2003:1-15 ↑

- http://www.cgdev.org/page/demographics-and-poverty ↑

- Therese Heketh, Xudong Zhou, Yun Wang, The end of the one-child policy. The Journal of The American Meidical Association 2015 ↑

- http://www.cnbc.com/2015/10/30/why-chinas-child-policy-doesnt-add-up-for-its-citizens.html ↑

- http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-abandons-one-child-policy-1446116462 ↑

- http://alexatsintolas.weebly.com/gendercide-and-human-rights-violations.html ↑

- http://alexatsintolas.weebly.com/gendercide-and-human-rights-violations.html ↑