Photo by John Reed on Unsplash

Written by Adam Terragnoli

Edited by Kristen Angierski and Elisabeth Lembo

The transcontinental flight from New York’s JFK Airport to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) traverses “flyover states” or “flyover country,” terms describing rural areas of the United States. Since the 2008 financial crisis, “flyover country” has experienced significant economic decline, a stark contrast to the post-recession recovery seen in highly-populated urban areas.[1] Negative economic outlooks have led to decreases in the quality of public services such as healthcare, education, food, and infrastructure. Moreover, since the Great Recession, rural areas have experienced what researchers have called, “the Great Reshuffling,” or the movement out of rural areas to highly populated cities.[2]

Although the challenges faced by rural America appear onerous, certain areas have shown signs of economic strength and resilience. One step the U.S. government is taking to improve conditions in rural areas is investing almost $700 million in rural broadband internet and e-Connectivity. Proponents believe that strengthening internet infrastructure will not only assist economic recovery, but also have positive externalities that will connect people to resources related to healthcare, education, food, and infrastructure.

Where is Rural?

Differentiating rural from urban areas poses a challenge since definitions of “rural” vary. According to the United States Census Bureau, rural is defined as “what is not urban – that is, after defining individual urban areas, rural is what is left,” which accounts for approximately 97% of the U.S.[3] [4] Using a different methodology, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) asserts that 72% of the landmass is rural.[5] Other U.S. Government agencies choose from more than two dozen definitions, and other terms, such as “Metro” and “NonMetro”.[6]

Percentage differences notwithstanding, less than 20%, or one in five people, live in a geographically rural area.[7] Although each community is unique, certain trends have been observed – rural America has become older, poorer, and less populated.[8]

Rural Decline

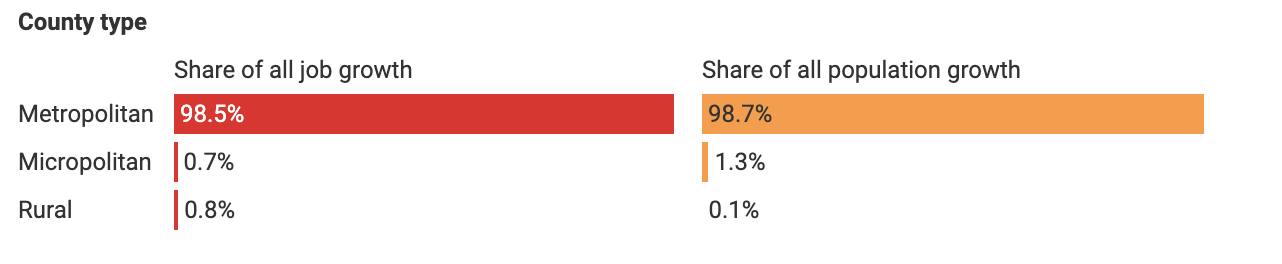

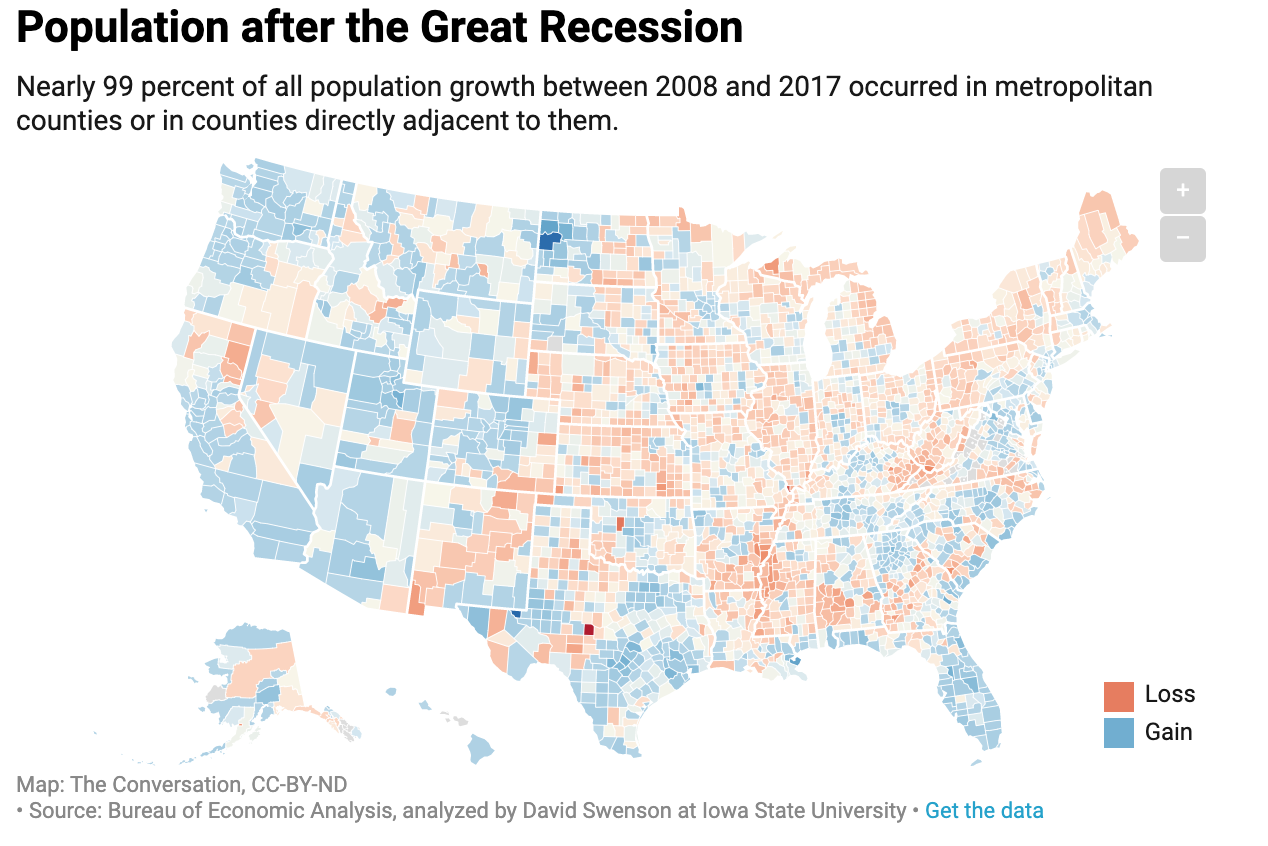

For the last half-century, millions of rural residents have observed the communities around them change. During the post-WWII era, rural areas were often burgeoning hubs of industrialization. But, as automation increased, workers were replaced with technology and began migrating to more densely populated areas.[9] The 2008 Recession exacerbated these conditions, and led to what researchers have termed “the Great Reshuffling”.[10] Between 2008 and 2017 almost all of the population and job growth occurred in metropolitan areas.[11]

Figure 1: Job and Population growth between 2008 to 2017[12]

Figure 2: Population Gain or Loss after the Great Recession[15]

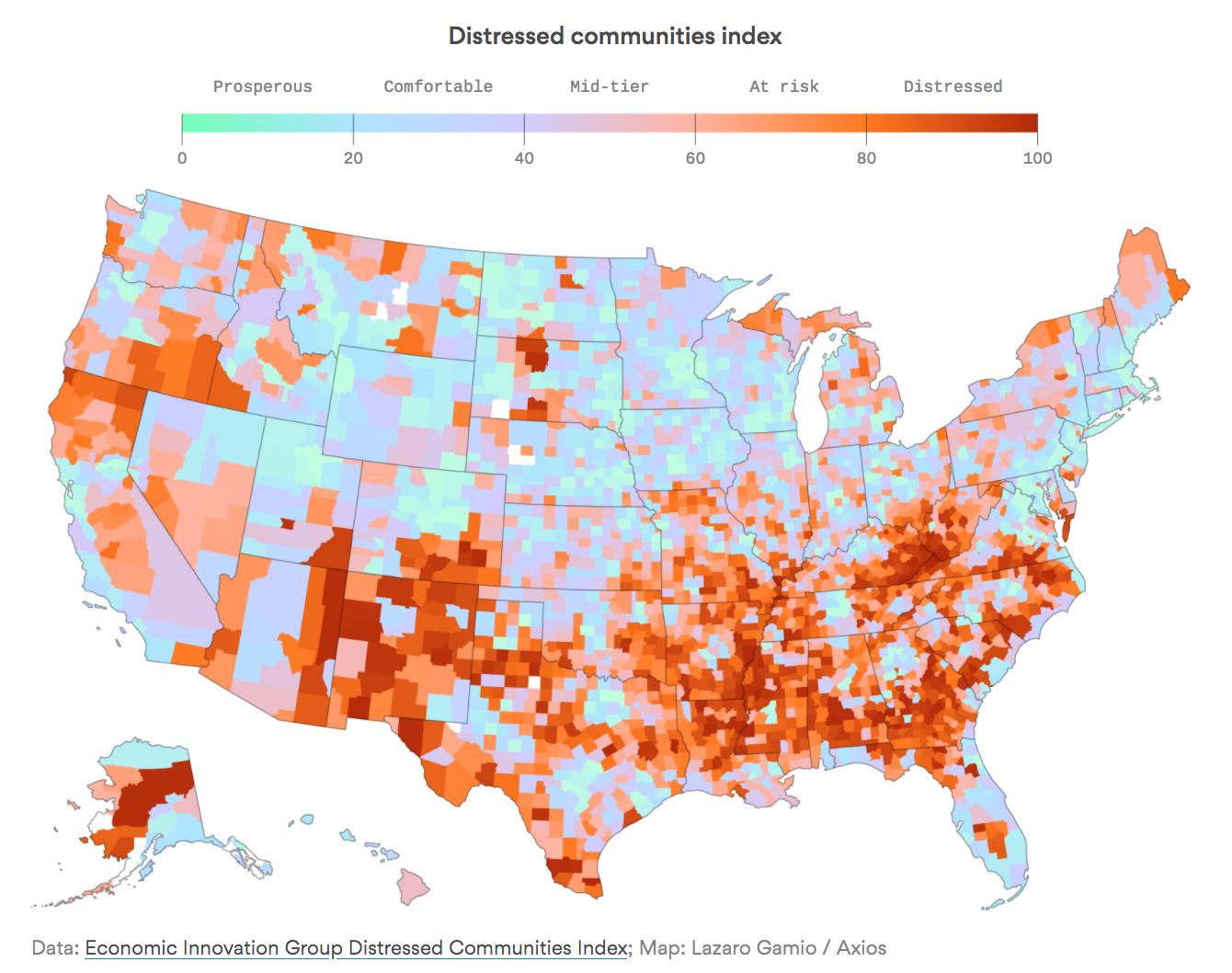

Figure 3: Distressed Communities Index by US County[18]

Bridging the Rural Broadband Gap

Rural communities each face a unique set of challenges, but a common theme appearing in many is unreliable internet. In their 2018 Broadband Deployment Report, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) stated that out of the 24 million households that are without reliable internet, 80 percent of them are in rural areas.[19] The U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Purdue, said “without access to broadband, entire communities are increasingly left behind in today’s information-driven economy. By connecting our communities, we are reconnecting Americans with one another and helping to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to benefit from this booming economy.”[20] Although USDA has invested in rural infrastructure for decades, current programs provide more than $700 million for modern broadband e-Connectivity.[21]

In 2018, the US Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2018, which dedicated $600 million additional funds for broadband expansion.[22] The USDA Task Force on Agriculture and Rural Prosperity said, “e-Connectivity is fundamental for economic development, innovation, advancements in technology, workforce readiness, and improved quality of life.”[23] The USDA also believes that increasing e-connectivity could pave the way for new agricultural technologies. By simply enhancing digital agricultural technologies being used today, USDA claims that an additional $47 billion gross benefit could be generated.[24] In February 2020, the FCC established a $20 billion rural broadband fund. Over the next decade, the goals of this program are two-fold: first, to encourage competition among phone and cable companies, and second, to provide subsidies to areas without internet access.[25]

The private sector has also played a role in increasing rural internet. In 2017, Microsoft launched the Microsoft Airband Initiative.[26] This program set out to achieve the “ambitious but achievable goal” of closing the rural broadband gap within five years (2022). Because of the initiative’s success in their first year, Microsoft raised its goal, from connecting two million people to three million people by July 2022.[27] Microsoft also brings a new technological advancement to the broadband space: their TV White Spaces technology. TV White Spaces utilizes an unused spectrum, meaning the technology can leverage current technologies to deploy wireless networks. As a part of their plan, Microsoft agreed to license TV White Space patents for free to anyone, including competitors.

Critics point out that because of a lack of population density, building internet infrastructure can be expensive and in some cases, prohibitive.[28] Will Rinehart from the American Action Forum assessed the claim that broadband leads to better economic outcomes.[29] Reinhart found that a distinction needed to be made between “presence” of broadband and “adoption” of broadband. His findings showed that the mere presence of broadband “[did] little to explain the unemployment rate, median household income, the change in employment, or the rate of population change” but when broadband adoption was measured, trends were better explained.

Conclusion

Time will tell whether or not the efforts to close the rural broadband gap will be successful. Stakeholders in this effort recognize the positive externalities that could come from connecting communities, such as access to health services, education, and infrastructure improvements. Brad Smith, President of Microsoft, said “Without a proper broadband connection, these communities can’t start or run a modern business, access telemedicine, take an online class, digitally transform their farm, or research a school project online,” he adds, “You see this dilemma play out in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics employment data, which shows the highest unemployment rates are frequently located in the counties with the lowest availability of broadband. As a nation, we can’t afford to turn our backs on these communities as we head into the future”.[30]

References

- Economic Innovation Group. “From Great Recession to Great Reshuffling: Charting a Decade of Change Across American Communities,” October 2018. https://eig.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-DCI.pdf. ↑

- Michael Ratcliffe, Charlynn Burd, Kelly Holder, and Alison Fields, “Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau,” ACSGEO-1, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2016. ↑

- Nasser, Haya El. “What Is Rural America?” The United States Census Bureau, May 23, 2019. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2017/08/rural-america.html. ↑

- United States Department of Agriculture. “Rural America at a Glance, 2017 Edition” 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/85740/eib-182.pdf?v=0 ↑

- Cromartie, John, and Shawn Bucholtz. “Defining the ‘Rural’ in Rural America.” USDA ERS – Defining the “Rural” in Rural America, June 1, 2008. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2008/june/defining-the-rural-in-rural-america/. ↑

- Ibid. 4 ↑

- Ibid. 1 ↑

- Ibid. 1 ↑

- Economic Innovation Group “Distressed Communities Index” from https://eig.org/2017-dci-map-national-counties-map and https://www.axios.com/americas-fractured-economic-well-being-2488460340.html ↑

- Swenson, David. “Most of America’s Rural Areas Are Doomed to Decline.” The Conversation, July 8, 2019. http://theconversation.com/most-of-americas-rural-areas-are-doomed-to-decline-115343. ↑

- Ibid. 11 ↑

- Swenson, David. “Dwindling Population and Disappearing Jobs Is the Fate That Awaits Much of Rural America.” MarketWatch, May 24, 2019. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/much-of-rural-america-is-fated-to-just-keep-dwindling-2019-05-07. ↑

- Hyde, Harlow A. “Slow Death in the Great Plains.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, September 26, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1997/06/slow-death-in-the-great-plains/376882/. ↑

- Ibid. 11 ↑

- Economic Innovation Group “Distressed Communities Index” from https://eig.org/2017-dci-map-national-counties-map and https://www.axios.com/americas-fractured-economic-well-being-2488460340.html ↑

- USDA. “Rural Poverty & Well-Being.” USDA ERS – Rural Poverty & Well-Being. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/. ↑

- Ibid. 11 ↑

- FCC. “2018 Broadband Deployment Report.” Federal Communications Commission, February 5, 2018. https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/broadband-progress-reports/2018-broadband-deployment-report. ↑

- United States Department of Agriculture. “Broadband.” USDA. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://www.usda.gov/broadband. ↑

- Ibid 12 ↑

- USDA. “Report to the President of the United States from the Task Force on Agriculture and Rural Prosperity” 2017. From https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/rural-prosperity-report.pdf ↑

- United States Department of Agriculture. “Rural Prosperity.” USDA. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://www.usda.gov/topics/rural/rural-prosperity. ↑

- Ibid 11 ↑

- Reid, Jon. “FCC Establishes $20 Billion Rural Broadband Expansion Fund (1).” Bloomberg BNA News. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/tech-and-telecom-law/fcc-establishes-20-billion-rural-broadband-expansion-fund. ↑

- Microsoft. “Rural Broadband Access & Connectivity – Microsoft CSR.” Rural Broadband Access & Connectivity. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/corporate-responsibility/airband. ↑

- Microsoft News Center. “Microsoft Increases Commitment to Eliminate the US Rural Broadband Gap.” Stories, December 4, 2018. https://news.microsoft.com/2018/12/04/microsoft-increases-commitment-to-eliminate-the-us-rural-broadband-gap/. ↑

- Swanson, Bret. “Rural broadband: It’s complicated” American Enterprise Institute. AEIdeas. 2018. https://www.aei.org/technology-and-innovation/telecommunications/rural-broadband-its-complicated/ ↑

- Reinhart, Will. “A Look At Rural Broadband Economics” 2018. Research. From https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/a-look-at-rural-broadband-economics/ ↑

- Ibid. 20 ↑