Source: Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD)

Written by: Michelle Soderling, Ryan Filbin, Michaela Borkovec

Edited By: Nida Mahmud

Flooding and Environmental Injustice

While considering water-related impacts of climate change on disadvantaged communities, researchers often study coastal marine environments for social and environmental injustices. Coastal disasters and systemic failures of disaster response, such as with Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, have led to an expansion in research of the unjust impacts of flooding on disadvantaged urban communities.[1] This study focuses on the impacts of recurring urban inland flooding in Milwaukee – specifically the disproportionate impacts on socially vulnerable individuals with lesser adaptive capacity than other communities.

This research observes environmentally-based injustices to residents due to repeated flooding of Lincoln Creek— a tributary of the Milwaukee River— as well as flooding of northern neighborhoods of the 30th Street Corridor of Milwaukee. These neighborhoods are historically inhabited by minority and low-income individuals, i.e. groups with high social vulnerability to environmental problems such as flooding. Descriptions of environmental justice (EJ), Schlosberg’s Dimensions of Environmental Justice, and the Cabreras’ Systems Thinking help provide the conceptual frameworks for analyses of this case study.[2] [3]

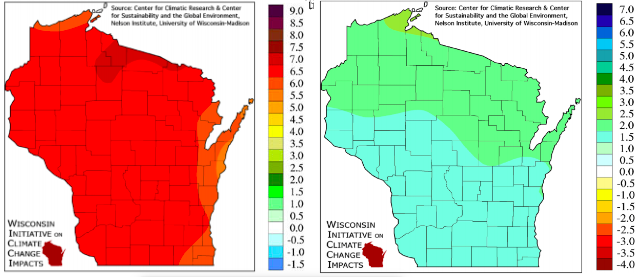

Potential water-related impacts of climate change stem from projected changes in seasonal and annual temperature and precipitation patterns. The Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI) predicts an increase of 4-9°F in average annual temperature across the state from 1980 to 2055, with an increase of roughly 6°F in average annual temperature in Milwaukee County.[4] Similarly, WICCI predicts a statewide increase in average annual precipitation from 1980 to 2055, with an increase of roughly one and a half inches in Milwaukee County[5] Local and regional climate change will potentially impact groundwater baseflow, impervious surface runoff, and the significance of extreme flooding events.

Figure 1 (left): Projected Changes, Average Annual Temperature

Figure 2 (right): Projected Changes, Average Annual Precipitation (Source: Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, 2009)

Social vulnerability to climate change is greatest throughout low-income and minority communities. Impoverished areas have lower adaptive capacities due to the economic importance of water resources and the limited capital of government institutions and citizens.[6] Urban environments have high social vulnerability due to being situated in hazardous locations, including the mouths of rivers and coastal settings. [7] Flooding, water security, and other climate impacts disproportionately disrupt the livelihoods of disadvantaged stakeholder groups.[8] Minority and low-income individuals lack the economic capital and social standing to respond to damages in the event of a disaster.[9]

The distribution of flooding vulnerability in Milwaukee is impacted by aging infrastructure and the inability of low-income residents to implement flood mitigation practices. Flood damage in Milwaukee is a water-related environmental injustice and, with predictions of increased precipitation for the Milwaukee area, this environmental injustice had the potential to become much worse if not controlled.

Conceptual Frameworks: Environmental Justice and Systems Thinking

Environmental Justice (EJ) has been a priority of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) since President Clinton signed Executive Order 12898 on February 11, 1994. This order mandated federal agencies to create interagency work groups to research and collect data while including public participation and access to information regarding the development and enforcement of environmental policies.

Schlosberg describes the dimensions of Environmental Justice (EJ) as distributive justice, procedural justice, and justice by recognition. [10] Distributive (in)justice refers to the equal or unequal distribution of common environmental features. Procedural or participatory justice is concerned with the groups that have a voice in environmental regulation, policy, and overall decision-making. Justice by recognition includes the understanding of inherited differences between groups of people, which must be considered in the discoursed of environmental policy and communicating the discourses to the public. Distributive and procedural justices or injustices directly reflect justices or injustices in-group recognition throughout policy and decision-making.

Derek and Laura Cabrera, professors at Cornell University, introduced Systems Thinking as a tool for addressing and conceptualizing “wicked problems”.[11] Originating from smaller problems, wicked problems represent cases where issues are linked across multiple agencies and stakeholder groups, with conflicting views over the root problems and potential solutions. Systems thinking has evolved to emphasize “thinking,” including the cognitive and emotional factors that create inaccurate mental models of real-world issues.

Four simple rules or patterns provide the framework for systems thinking: Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives.[12] The DSRP rules are interrelated and each rule involves co-implication. Distinctions consider that an idea or thing can be differentiated from other ideas or things, and each distinction has a unique identity. Systems consider that an idea or thing can be split up or lumped together, and a system is defined as being made up of an interaction between a part and a whole. A system is also a distinction, and a system may contain other sub-systems and distinctions. Relationships are made up of an action and a reaction, and relationships connect distinctions or systems to one another. Perspectives are made up of an interaction between a point and a view— where a point is that which is being focused on, and the view is that which is doing the focusing. Every distinction made, every system and relationship identified, is affected by perspective.

The conceptual frameworks of EJ and DSRP are utilized in this analysis of flooding throughout Lincoln Creek and 30th Street Corridor communities. Injustices of recognition with regards to flooding and how recognition injustices underlie procedural and distributional injustices are analyzed by using Schlosberg’s dimensions of EJ. Plectica Visual Mapping Software is used to map the systems thinking analysis of this case study.[13] Both EJ and DSRP analyses rely on archival research, including policy documents and news reports.

History of Flooding of Lincoln Creek and the 30th Street Corridor

According to Clean Wisconsin, Wisconsin is likely to see increased floods and more severe weather events due to climate change.[14] Milwaukee has faced several flooding events of varying intensity over the years, the worst of which occurred in 2010. During the afternoon and evening of July 22, 2010, there were record-setting heavy rains, leading to flash flooding in southeastern Wisconsin. The brunt of the flooding hit the Milwaukee Metro Area, where it rained over seven inches in just a few hours, causing over thirty million dollars in damage.[15] In Milwaukee County, several thousand homes were affected. Over 4,400 homes were reported with water-filled basements in the city of Milwaukee alone.[16]

The hardest hit areas included Shorewood, Glendale, and along Lincoln Creek. Nestled next to Lincoln Creek are the northern neighborhoods of the 30th Street Corridor, which, on July 22, 2010, were drenched with more rainwater than other portions of the Milwaukee Metro Area— this area specifically was hit with more than eight inches of rain. The Lincoln Creek area is made up of primarily low-income and minority citizens and is the only place where the flash flooding caused a fatality. A nineteen-year-old male was swept from his vehicle when Lincoln Creek flooded.[17]

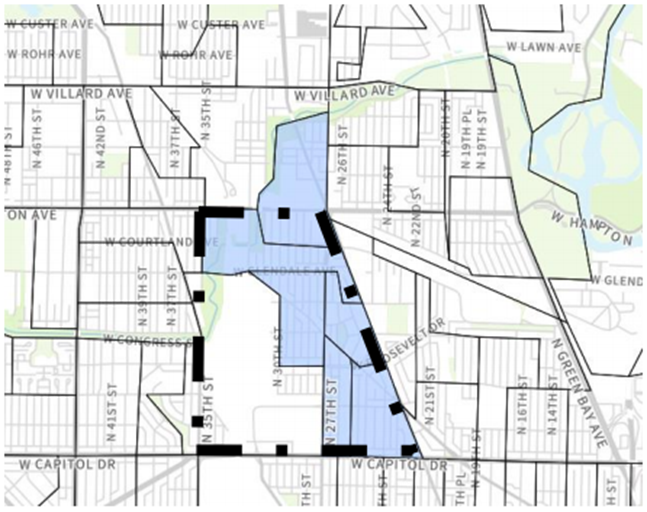

Figure 3: Garden Homes, a neighborhood in the northern portion of the 30th Street Corridor. Northern reaches of Garden Homes touch Lincoln Creek. This low-lying neighborhood was heavily impacted by the 2010 Milwaukee Flood. (Source: Garden Homes Demographic Report [18])

The 30th Street Corridor is a low-lying landscape that just could not absorb all the water that drained its way.[19] It took less than a day for the flood water to damage Garden Homes severely. Garden Homes (Figure 3) is a neighborhood in the northern portions of the 30th Street Corridor that comprises minority and low-income citizens. According to the 2015 estimates of the Census Bureau, Garden Homes has a population of 4,620 people. Of these, 4,485 (ninety-seven percent) are Black or African American, a higher percentage than the city as a whole where African Americans make up thirty-nine percent of the total population.[20] Household incomes in Garden Homes are lower than the City of Milwaukee as a whole, and the percentage of households in all categories below thirty thousand dollars is much higher in Garden Homes than citywide.[21] Currently, MMSD and the City of Milwaukee are completing a project in the 30th Street Corridor aimed at increasing the area’s capacity to control flood water (Figure 4). The 30th Street Corridor Project includes transforming vacant industrial space into green space capable of soaking up flood water.[22] The 30th Street Corridor Project goal is to protect neighborhoods and businesses against the one-percent probability flood, commonly called the 100-year flood.[23]

Figure 4: Vision for Eastern Flood Basin in the 30th Street Corridor (Source: MMSD [24])

The magnitude of the 2010 flooding around Lincoln Creek came as a surprise to many residents after an extensive flood-control project by MMSD in 2002. The area flooded during heavy rains in the preceding decades. To control flood damage, more than 2,000 homes and businesses were removed, and detention basins capable of storing eighty million gallons were created.[25] Still, the 2010 flooding caused severe damage and collapsed several basements. Once the area lost electricity, sump pumps stopped working and water continued rushing into homes.[26] The dirt and foundations were washed away from homes along the 5000s block of N 19th Place, exposing clothing and household goods floating in basements.[27] Many irreplaceable family items are destroyed in the flooding, and flood damage can be financially as well as emotionally devastating to those individuals affected.

Figure 5 (left): A sinkhole due to the 2010 flood (Source: MMSD[28])

Figure 6 (right): A home after the flood of 2010 (Source: MMSD[29])

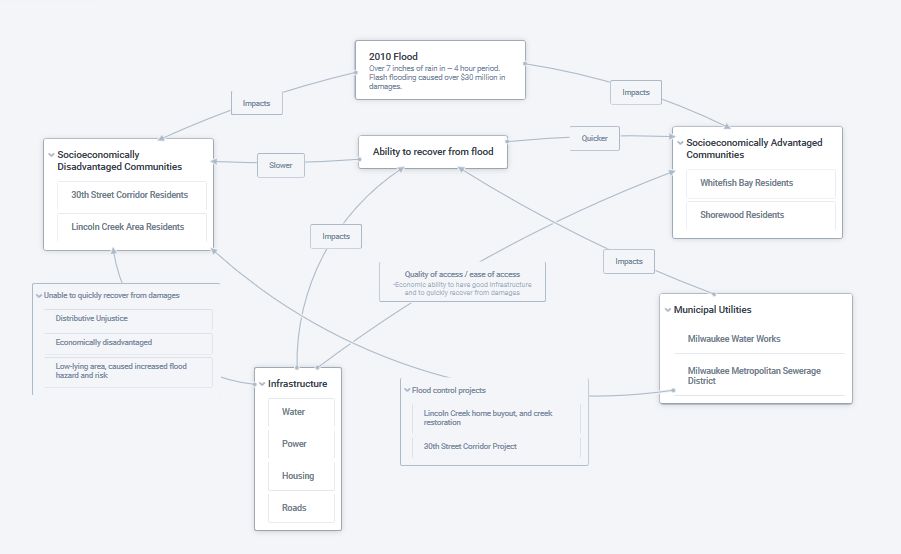

The constructed environment in urban communities impacts the level of hazard a community faces when flooding occurs. Low-income communities, like those surrounding Lincoln Creek as well as the northernmost 30th Street Corridor communities, do not have the resources to recover quickly or efficiently from flood damage. Flood water in these socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (e.g. Lincoln Creek and the 30th Street Corridor) had a greater impact than it did on socioeconomically advantaged communities (e.g. Shorewood and Whitefish Bay (Figure 7)). Many homes were safe or quickly repaired in Whitefish Bay, while homes near Lincoln Creek lost power, filled with water, and in some cases were swept away by flood waters.

Around 1,300 homes and businesses remain in the 100-year floodplain in Milwaukee County, down from 3,800 in 1999.[30] Although a one percent chance of flooding every year seems unlikely, more frequent and more severe flooding has been a side effect of climate change. MMSD has invested hundreds of millions of dollars to address the increasing risk of flooding in the Milwaukee area. In an attempt to mitigate severe flooding, MMSD has created a Greenseams program, a form of green infrastructure that stores and drains water into the ground naturally.[31]

The minority and low-income communities of Lincoln Creek and northern portions of the 30th Street Corridor struggle with aging water infrastructure, such as the combined sanitary and stormwater sewer system.[32] These communities rely on the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) when severe storms cause damage to their properties. The issue in this area is that flooding is often caused by combined sewer backups into streets and basements. Unfortunately, flooding from sewer backups is not covered under NFIP, leaving the homeowners to bear the full cost of the damage.[33]

Dimensions of Environmental Justice

Recognition

Residents of the Lincoln Creek and 30th Street Corridor communities bear the inequities and systemic failures of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Reforms made under the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 have created significant increases in the annual flood insurance premiums for subsidized properties in high-risk flood zones.[34] Changes in flood insurance premiums may lead homeowners to risk non-compliance of flood insurance regulations or be unable to pay their mortgages. Furthermore, mortgage lenders and borrowers recognize that future increases in the spatial distribution of flood zones from climate change may impact the stability of the local housing market.[35] Homeowners enrolled in NFIP have failed to recognize the scope of insurance coverage, which does not include sewer backups such as with the Milwaukee flooding in 2010. Since reports of backwater in basements are arbitrarily defined and it is difficult to pinpoint the source of the water, many homeowners are left to bear the costs of flooding to their foundations.[36]

Officials with the City of Milwaukee recognize the problems of flooding, but they lack the understanding of spatial differences in flooding necessary to improve flood management infrastructure. Public works officials do not track where waters come from during flood events. The City of Milwaukee can improve flood management by identifying and recognizing basement flooding sources, such as with the communities of Shorewood, Whitefish Bay, and Wauwatosa.[37]

Procedural

Under the Federal Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973, flood insurance is required for federal or federally related funding for the construction or acquisition of property in a FEMA-designated high-risk flooding zone.[38] Many residents in the Lincoln Creek and 30th Street Corridor neighborhoods are required to participate in the NFIP. The involuntary participation in the NFIP creates injustices for renters and homeowners who are unable to afford rising insurance premiums as flood risks increase with climate change, or as sewer backups, which are not covered under the NFIP, become more prevalent.[39] [40]

Some homeowners near Lincoln Creek voluntarily participated in selling their homes to make way for a new flood basin. MMSD purchased three empty lots and seven homes in the area. Houses were deconstructed, salvaging material to be used again or recycled. The eastern flood basin (Figure 4) is expected to hold almost two million gallons and was designed to incorporate aesthetic, recreational, and safety concepts that neighbors desired, including a usable green space.[41] The participation of these homeowners and residents in neighborhood decisions is an example of participatory justice initiatives in Milwaukee.

The City of Milwaukee, MMSD, along with several nonprofits in the city, have programs that incorporate small-scale green infrastructure into Milwaukee communities. Many small-scale green infrastructure projects focus on harvesting rainwater. There are small-scale green infrastructure projects happening in the 30th Street Corridor due to several non-profit groups working to help manage water where it falls for a more equitable water future. Reflo facilitates cistern building projects for water catchment, Milwaukee Riverkeeper hosts rain barrel workshops, and Clean Wisconsin helps citizens plant rain gardens.[42] [43] [44] Other projects involve creating green roofs and planting stormwater trees. These features are designed to increase the resilience of communities against flooding due to climate change. One limitation with procedural justice is that many community members are not homeowners and cannot physically alter their dwelling places to include green infrastructure. Another challenge is that Milwaukee lacks sufficient educational resources for diverse audiences on how climate change itself affects residents and their communities. Without sufficient educational and outreach initiatives pertaining to how climate change impacts water systems, it is difficult to engage residents in meaningful participation. Green infrastructure initiatives should engage community members, as well as educate them about climate change and urban water systems.

Distributive

Climate change is predicted to cause an additional one and a half inches of precipitation every year in Milwaukee.[45] Vulnerable communities within the 30th St. Corridor and along Lincoln Creek are currently struggling with aging water infrastructure, an inability to fund damage repairs due to flooding, and flood insurance that does not cover their losses. These areas of Milwaukee are dealing with lead pipes and water contamination and are impacted severely when sewers overflow due to flood waters.[46] The 30th St. Corridor lies above Milwaukee’s combined sewer system, but is a low-lying area where water readily flows. During large rainfall events, this area experiences sanitary sewer backups that flood the basements of homes and businesses. Many residents have flood insurance, but most damage from flooding is caused by basement backups which are not covered under flood insurance.[47] With climate change, damage caused by flooding is predicted to become worse in Milwaukee and other parts of southeastern Wisconsin.

Milwaukee Flooding and Systems Thinking

Systems thinking requires looking at problems by evaluating distinctions, systems, relationships, and perspectives at play. When analyzing cases of environmental injustice, it is useful to apply systems thinking to distinguish notable characteristics of problems and find resolutions. Finding resolutions for the expected water-related impacts of climate change on urban environments and populations involves tensions between the multiple systems that must work together. Identifying the systems and play and looking at how they work together is important in finding resolutions to the complex water injustices Milwaukee communities near Lincoln Creek are facing.

Examining water-related impacts of climate change on disadvantaged communities through a systems thinking lens prompts the questions: How and why do environmental problems affect different groups and individuals in different and unequal ways? What should be done to address these differences and inequalities?

There are many distinctions to consider when approaching water-related impacts on communities, including aging infrastructure, water shortages, increasing utility prices, and the vulnerability of the poor. Aging infrastructure is a primary concern because safe drinking water (i.e. water which meets Safe Drinking Water Act water quality standards and is not contaminated by toxic heavy metals like lead) and effective wastewater management (i.e. waste water moving away from homes, not backing up in basements) are fundamental for public health.[48] Additionally, the costs for utilities and utility repairs heavily increase negative impacts to disadvantaged communities.

Urban water systems have complex parts, such as potable, sanitary sewer, storm water, and natural ecological water systems. In Milwaukee, the combined sewer system intakes from both sanitary sewers and storm water drains. As a result, the likelihood of basement backups is increased under severe precipitation events. After losing power during the 2010 flooding, many residents in disadvantaged communities lost possessions and even walls from their homes (Figure 6) due to the flash-flood waters.

Distinguishing the 2010 flood from other events helped identify the severity of social and economic inequities within Milwaukee. Social and economic systems impact the ability of a community to recover from flood damage. Although some remediation efforts are in place, low-income and minority groups remain disproportionately excluded from access to flood-control, which makes them more vulnerable to increased precipitation from climate change. These environmental injustices make socioeconomically disadvantaged communities more vulnerable. As populations increase and climate change becomes more prevalent, communities need adaptive capacity to recover quickly and efficiently from climate-related impacts– including water damage due to increased precipitation and flooding.

The relationship between a community and their ability to recover from flood damage not only depends on geospatial factors, but also social and economic factors. The relationship between many low-income and minority groups and their access to resources to help adapt to flood damage is often lacking.

Figure 7: 2010 Milwaukee Flood Plectica Map. This diagram uses Systems Thinking methodology to show that both socioeconomically advantaged and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities are impacted by flooding, but disadvantaged communities are unable to recover as quickly as advantaged communities. [49]

Figure 7: 2010 Milwaukee Flood Plectica Map. This diagram uses Systems Thinking methodology to show that both socioeconomically advantaged and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities are impacted by flooding, but disadvantaged communities are unable to recover as quickly as advantaged communities. [49]

Gaps in Climate Change Policy and Literature

In recent years, the United States federal government has revoked many policies and initiatives, and removed language from government agencies regarding climate change. Some examples include the Federal Flood Mitigation Standard. The Federal Flood Mitigation Standard was a directive in 2015 which required public infrastructure projects that received taxpayer dollars to plan for floods, including elevating their structures to avoid future water damage, and thus alleviated the burden on taxpayers. This directive was revoked a few years later.[50] Although not acknowledged by the federal government, many states, cities, and organizations remain adamant about pursuing climate change mitigation and adaptation policies. Mayors of more than 1,000 US cities have pledged their commitment to the US Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement, despite budget proposals by the Trump administration to decrease funding to the EPA and to eliminate the Global Climate Change Initiative.[51]

Adequate Flood Insurance

A policy issue in Milwaukee communities is the lack of full coverage for flood insurance. Since the 30th St. Corridor communities are located near Milwaukee’s combined sewer system, many flood-related damages to properties are caused by sewer system backups. Minority and low-income communities of Lincoln Creek and the 30th Street Corridor struggle with poor and aging water infrastructure such as the combined sanitary and stormwater sewer systems.[52] As mentioned, these communities rely on the NFIP when severe storms cause damage to their properties.[53] Adequate flood insurance policies that cover sewer backups are a necessity in these communities, especially since they are required to participate in the NFIP.

Education

A major issue faced by communities throughout Milwaukee is the ability of stakeholders to conceptualize how the science-based information of climate changes impacts their lives. The City of Milwaukee, MMSD, and many nonprofits have small climate change mitigation and adaptation programs, but Milwaukee is lacking in educational resources about how climate change itself affects residents and their communities. Extensive educational and outreach programs would be beneficial, especially to increase the adaptability and resilience of vulnerable communities from flood damage. Without extensive educational and outreach materials pertaining to climate change impacts on water systems, it is difficult to engage residents in actively getting involved in a meaningful way.

Milwaukee’s Water Future

The City of Milwaukee has socioeconomically and environmentally vulnerable communities, such as those within the 30th St. Corridor. The United States lacks policies regarding climate change and vulnerable communities. Low-income and minority communities in the Milwaukee area are disproportionately impacted by water-related impacts of climate change. This proved true in 2010 when flash-flood waters heavily damaged communities in the northern portion of the 30th St. Corridor. There was very little resilience to damages from flood waters in the low-income and minority communities of the Corridor.

Milwaukee is lacking in adequate water infrastructure, flood insurance policies, and education in low-income and minority communities. It is critical for Milwaukee to develop resilience to water-related impacts of climate change and to focus efforts on vulnerable communities. Policies for climate change adaptation and mitigation, including education and implementation of green infrastructure, are necessary for Milwaukee to prepare for water-related impacts of climate change on low-income and minority citizens.

Building green water infrastructure in vulnerable communities can build community resilience by reducing social vulnerability, i.e. the incapacity of residents to deal with environmental hazards.[54] Milwaukee communities would benefit from implementing adaptation and mitigation models like the City of Detroit’s Green Infrastructure Spatial Planning (GISP) model. The GISP is a GIS-based multi-criteria approach that integrates six benefits: 1) stormwater management; 2) social vulnerability; 3) green space; 4) air quality; 5) urban heat island amelioration; and 6) landscape connectivity.[55] According to Meerow & Newell, cities like Detroit are using models like these to expand green infrastructure and improve community resilience and ecosystem services.[56] The City of Milwaukee’s Environmental Collaboration Office developed a Green Infrastructure Baseline Inventory to document the city’s current capacity for green infrastructure and to target the creation of a Green Infrastructure Policy Plan.[57]

Geographic Information Science (GIS) has been integrated into justice and green infrastructure assessment frameworks for identifying social-ecological vulnerability in communities and prioritizing investments in infrastructure.[58] The City of Milwaukee utilizes a Green Infrastructure GIS tool to promote open data sharing, public communication, and advancements in green infrastructure planning throughout the city.[59] Using GIS to study the spatial distribution of climate justice in urban flood planning may improve communication of environmental risks to vulnerable populations through means such as workshops and policy briefs.

The adaptive capacity and flood resiliency of Milwaukee may be strengthened through collaborative efforts with other cities facing similar climate change effects. 100 Resilient Cities is a project by the Rockefeller Foundation that supports the capacity of cities to respond to increasing physical, social, and environmental challenges.[60] The project uses a holistic approach to shocks and stresses, believing that a city will adapt better to climate change if it can better respond to other stresses from globalization and urbanization.[61] Chicago and Minneapolis— areas projected to experience similar climate changes as Milwaukee— are both member cities of the 100 Resilient Cities. Milwaukee may also benefit from adopting elements of the Detroit Climate Action Collaborative (DCAC) to conduct vulnerability assessments for flooding and other climate change impacts, and to identify work groups in the city for improving collaborative action.[62]

Educational and outreach programs for climate change and flooding in Milwaukee may adopt the three Rs approach of reclamation, resilience, and regeneration.[63] Reclamation creates systems to reclaim lost cultural and social resources; expanding green infrastructure and urban agriculture in the study area would bring together different social groups and promote environmental learning. Resilience is the ability to respond and recover from environmental stressors; environmental education in the study area can promote the community and psychological resilience to urban flooding. Regeneration involves ever-evolving transformations of societal capacities— including approaches for a greater adaptive capacity as well as mitigation strategies for climate change and flooding. Regeneration utilizes responsive education, including community engagement in green infrastructure, which can promote future engagement in flood adaptation and mitigation.[64]

Conclusion

The City of Milwaukee is lacking adequate water infrastructure, flood insurance, and education in low-income and minority communities. These communities, like those in the Lincoln Creek and 30th St. Corridor areas, continuously and disproportionately suffer from the negative water-related impacts of climate change. By implementing climate change adaptation and mitigation plans, focusing on vulnerable communities for climate change education and green infrastructure, and allowing for improved flood insurance policies, Milwaukee’s communities will become much more resilient to climate change impacts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Ryan Holifield and Dr. Deidre Peroff for inspiring our work in freshwater and social justice, introducing us to the dimensions of environmental justice and systems thinking, and for supporting our collaborative research aims.

References

- Timothy Collins and Sara Grineski. “Environmental Justice and Flood Hazards: A Conceptual Framework Applied to Emerging Findings and Future Research Needs.” In The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice, by Ryan Holifield, Jayajit Chakraborty and Gordon Walker, (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group), 350-361. ↑

- David Schlosberg, “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories,” Environmental Politics 13, no. 3. (2004): 517- 540. ↑

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, “New Hope for Wicked Problems,” in Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems, (USA: Plectica Publishing, 2015), 12-20. ↑

- “How Is Wisconsin’s Climate Changing.” Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts – WICCI. https://www.wicci.wisc.edu/climate-change.php. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Piya Abeygunawardena, Yogesh Vyas, Philipp Knill, Tim Foy, Melissa Harrold, Paul Steele, Thomas Tanner, Danielle Hirsch, Maresa Oosterman, Jaap Rooimans, Marc Debois, Maria Lamin, Holger Liptow, Elisabeth Mausolf, Roda Verheyen, Shardul Agrawala, Georg Caspary,Ramy Paris, Arun Kashyap, Arun Sharma, Ajay Mathur, Mahesh Sharma, Frank Sperling. Poverty and Climate Change: Reducing the Vulnerability of the Poor through Adaptation. Working paper. Vol. 1. (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2009). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/534871468155709473/Poverty-and-climate-change-reducing-the-vulnerability-of-the-poor-through-adaptation. ↑

- Rebecca Gasper, Andrew Blohm, and Matthias Ruth. “Social and Economic Impacts of Climate Change on the Urban Environment.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability3, no. 3 (2011): 150-57. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2010.12.009. ↑

- Matthias Ruth and María E. Ibarrarán. “Distributional Effects of Climate Change – Social and Economic Implications.” Distributional Impacts of Climate Change and Disasters, August 31, 2009, 2-7. doi:10.4337/9781849802338.00008. ↑

- Caroline Moser and David Satterthwaite. Toward Pro-Poor Adaptation to Climate Change in the Urban Centers of Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Working paper. (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2008). http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/10564IIED.pdf ↑

- David Schlosberg, “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories,” Environmental Politics 13, no. 3. (2004): 517- 540. ↑

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, “New Hope for Wicked Problems,” in Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems, (USA: Plectica Publishing, 2015), 12-20. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Plectica Visual Mapping Software. https://www.plectica.com/maps/UIH5TM9OL/edit/JEZON9G4W. ↑

- Clean Wisconsin. http://www.cleanwisconsin.org/. ↑

- US Department of Commerce, and NOAA. “2010, July 22, Flash Flooding & Tornado Outbreak.” National Weather Service. April 05, 2015. https://www.weather.gov/mkx/072210_flashflooding-tornadoes. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “Garden Homes Demographic Report.” The 30th Street Industrial Corridor Corp (The Corridor). http://www.thecorridor-mke.org/garden-homes-demographic-report/. ↑

- “30th Street Corridor – Flood Relief.” MMSD: Partners for a Cleaner Environment. https://www.mmsd.com/what-we-do/flood-management/30th-street-corridor. ↑

- “Garden Homes Demographic Report.” The 30th Street Industrial Corridor Corp (The Corridor). http://www.thecorridor-mke.org/garden-homes-demographic-report/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jonathon Gregg. “Seven Inches of Rain in Four Hours: This Week Marks Four-year Anniversary of Massive Flash Floods.” FOX6Now.com. July 21, 2014. http://fox6now.com/2014/07/20/seven-inches-of-rain-in-four-hours-this-week-marks-four-year-anniversary-of-massive-flash-floods/. ↑

- “30th Street Corridor – Flood Relief.” MMSD: Partners for a Cleaner Environment. https://www.mmsd.com/what-we-do/flood-management/30th-street-corridor. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Tom Held and Alex Morrell. “Milwaukee County Damage: $28.5 Million and Counting.” July 24, 2010. http://archive.jsonline.com/news/milwaukee/99156089.html. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “30th Street Corridor – Flood Relief.” MMSD: Partners for a Cleaner Environment. https://www.mmsd.com/what-we-do/flood-management/30th-street-corridor. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “Greenseams – Innovative Flood Management Program” MMSD: Partners for a Cleaner Environment. https://www.mmsd.com/what-we-do/flood-management/greenseams. ↑

- “Lead and Water.” Milwaukee Water Works. http://city.milwaukee.gov/water/WaterQuality/Lead-Awareness-and-Drinking-Water-Safety.htm#.WtY9tYjwbIU. ↑

- Dave Umhoefer. “Milwaukee Ald. Jim Bohl Says Sewer Backups Caused Most of the Damage in July Floods, and Federal Flood Insurance Doesn’t Cover It.” Politifact Wisconsin. November 16, 2010. http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2010/nov/16/jim-bohl/milwaukee-ald-jim-bohl-says-sewer-backups-caused-m. ↑

- Paul Gores. “Flood Insurance Costs on the Rise – Changes Enacted by Congress Lead the Increase.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel – Business. October 5, 2013. http://archive.jsonline.com/business/flood-insurance-costs-on-the-rise-b99112536z1-226590521.html. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Dave Umhoefer. “Milwaukee Ald. Jim Bohl Says Sewer Backups Caused Most of the Damage in July Floods, and Federal Flood Insurance Doesn’t Cover It.” Politifact Wisconsin. November 16, 2010. http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2010/nov/16/jim-bohl/milwaukee-ald-jim-bohl-says-sewer-backups-caused-m. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “Flood Insurance Requirement.” FEMA. https://www.fema.gov/faq-details/Flood-Insurance-Requirement. ↑

- Paul Gores. “Flood Insurance Costs on the Rise – Changes Enacted by Congress Lead the Increase.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel – Business. October 5, 2013. http://archive.jsonline.com/business/flood-insurance-costs-on-the-rise-b99112536z1-226590521.html. ↑

- Dave Umhoefer. “Milwaukee Ald. Jim Bohl Says Sewer Backups Caused Most of the Damage in July Floods, and Federal Flood Insurance Doesn’t Cover It.” Politifact Wisconsin. November 16, 2010. http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2010/nov/16/jim-bohl/milwaukee-ald-jim-bohl-says-sewer-backups-caused-m. ↑

- “30th Street Corridor – Flood Relief.” MMSD: Partners for a Cleaner Environment. https://www.mmsd.com/what-we-do/flood-management/30th-street-corridor. ↑

- Reflo. http://refloh2o.com/. ↑

- Milwaukee Riverkeeper. https://www.milwaukeeriverkeeper.org/water-conservation/. ↑

- Clean Wisconsin. http://www.cleanwisconsin.org/our-work/water/30th-street-mke/. ↑

- “How Is Wisconsin’s Climate Changing.” Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts – WICCI. https://www.wicci.wisc.edu/climate-change.php. ↑

- “Lead and Water.” Milwaukee Water Works. http://city.milwaukee.gov/water/WaterQuality/Lead-Awareness-and-Drinking-Water-Safety.htm#.WtY9tYjwbIU. ↑

- Dave Umhoefer. “Milwaukee Ald. Jim Bohl Says Sewer Backups Caused Most of the Damage in July Floods, and Federal Flood Insurance Doesn’t Cover It.” Politifact Wisconsin. November 16, 2010. http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2010/nov/16/jim-bohl/milwaukee-ald-jim-bohl-says-sewer-backups-caused-m. ↑

- “Drinking Water.” American Society of Civil Engineer’s 2017 Infrastructure Report Card. https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/cat-item/drinking-water/. ↑

- Plectica Visual Mapping Software. https://www.plectica.com/maps/UIH5TM9OL/edit/JEZON9G4W. ↑

- “Drinking Water.” American Society of Civil Engineer’s 2017 Infrastructure Report Card. https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/cat-item/drinking-water/. ↑

- Julia Haskins. “US Cities Taking the Lead on Combating Climate Change: Residents, Officials Coming Together.” The Nation’s Health. May 01, 2017. http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/47/3/1.3. ↑

- “Lead and Water.” Milwaukee Water Works. http://city.milwaukee.gov/water/WaterQuality/Lead-Awareness-and-Drinking-Water-Safety.htm#.WtY9tYjwbIU. ↑

- Dave Umhoefer. “Milwaukee Ald. Jim Bohl Says Sewer Backups Caused Most of the Damage in July Floods, and Federal Flood Insurance Doesn’t Cover It.” Politifact Wisconsin. November 16, 2010. http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2010/nov/16/jim-bohl/milwaukee-ald-jim-bohl-says-sewer-backups-caused-m. ↑

- Susan L. Cutter. “Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards.” Progress in Human Geography20, no. 4 (1996): 529-39. doi:10.1177/030913259602000407. ↑

- Sara Meerow and Joshua P. Newell. “Spatial Planning for Multifunctional Green Infrastructure: Growing Resilience in Detroit.” Landscape and Urban Planning159 (2017): 62-75. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.005. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Climate Adaptation and Green Infrastructure. http://city.milwaukee.gov/GI#.WvCBXqovyUk. ↑

- Chingwen Cheng. “Spatial Climate Justice and Green Infrastructure Assessment: A Case Study for the Huron River Watershed, Michigan, USA.” GI Forum1 (2016): 176-90. doi:10.1553/giscience2016_01_s176. ↑

- Climate Adaptation and Green Infrastructure. http://city.milwaukee.gov/GI#.WvCBXqovyUk. ↑

- 100 Resilient Cities. https://www.100resilientcities.org. ↑

- Julia Haskins. “US Cities Taking the Lead on Combating Climate Change: Residents, Officials Coming Together.” The Nation’s Health. May 01, 2017. http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/47/3/1.3. ↑

- Kelly Gregg, Peter McGrath, Sarah Nowaczyk, Karen Spangler, Taylor Traub, and Ben VanGessel. “Foundations for Community Climate Action: Defining Climate Change Vulnerability in Detroit.” A Sustainable Strategy for Clean Waterways (New York City) | Adaptation Clearinghouse. December 2012. https://www.adaptationclearinghouse.org/resources/foundations-for-community-climate-action-defining-climate-change-vulnerability-in-detroit.html. ↑

- Marna Hauk. “The New “Three Rs” in an Age of Climate Change: Reclamation, Resilience, and Regeneration as Possible Approaches for Climate-Responsive Environmental and Sustainability Education.” The Journal of Sustainability Education, February 16, 2017. http://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/the-new-three-rs-in-an-age-of-climate-change-reclamation-resilience-and-regeneration-as-possible-approaches-for-climate-responsive-environmental-and-sustainability-education_2017_02/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑