Senator Jorge Robledo during a roundtable with Cornell students and faculty regarding agriculture and trade issues.

The Cornell Policy Review interviewed Senator Jorge Robledo, from Colombia, during his visit to the Cornell campus in Ithaca. He talked about the recent rejection of the peace process agreement in Colombia and other relevant issues.

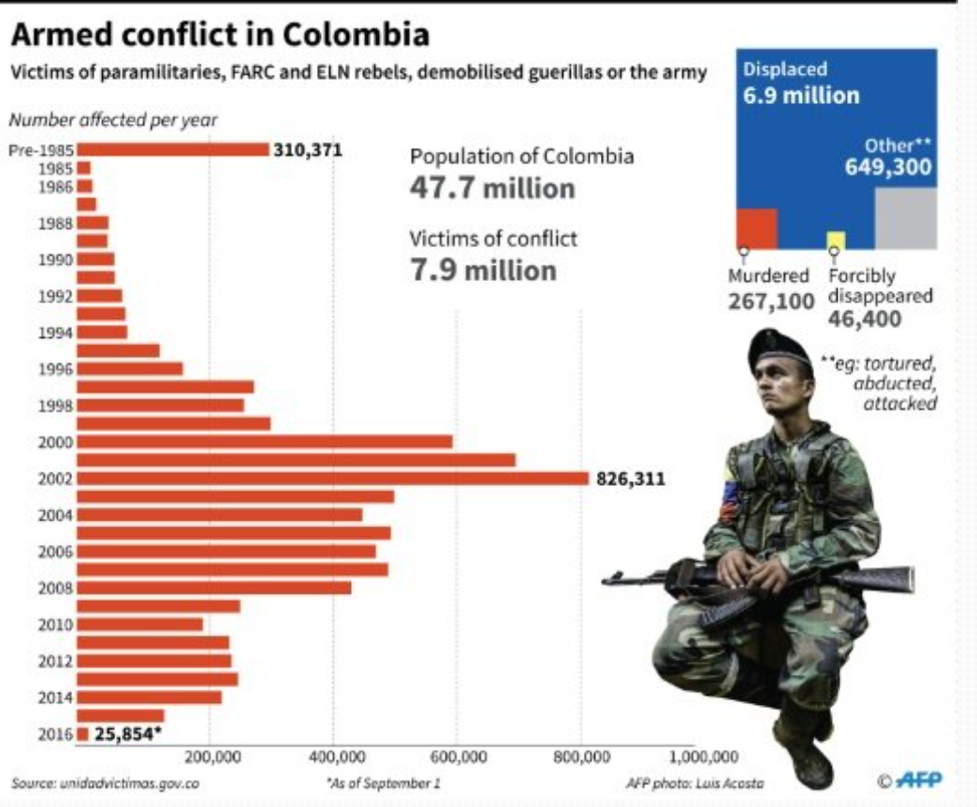

Ithaca, October 10th. Colombia has been in the center of the news during the last weeks as it prepared—and failed—to approve the peace process agreement between the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (or FARC, Spanish for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and the Government of Colombia.

In a trend that is starting to worry political scientists, results on referendums are having unpredicted results and outcomes that defy polls and political leaders are shocking nations such as Britain, Hungary, Thailand, and indeed Colombia.

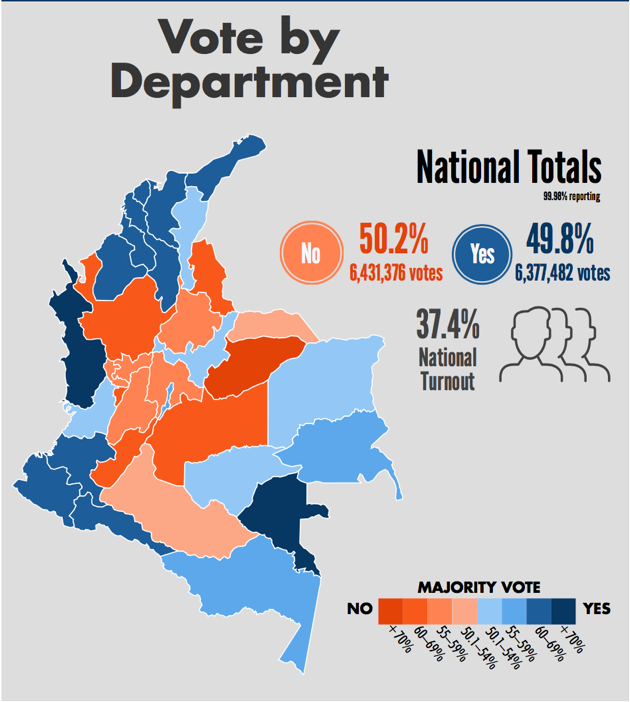

In orange, the departments that voted against the peace agreement; in blue, the departments that voted in favor of the peace agreement. The departments in the center are the less affected by the war with the FARC; the departments in the periphery have been the most affected by the war. Source: http://www.as-coa.org/articles/weekly-chart-colombias-no-vote-numbers

In Colombia´s case, the result was particularly surprising because of the nature of the decision—voting yes or no to a peace agreement that would end 52 years of internal war—and because the forecasts of different polls foresaw a two-to-one victory margin for the yes vote.

The effects of the war: number of victims of conflict, murdered and disappeared. Source: AFP

On these issues, and others relevant to Colombia and Latin America, we talked with Senator Jorge Robledo, who was visiting Cornell University for a series of roundtables and forums with Cornell students about the peace process, agriculture, and trade issues.

Senator Robledo is a member of the Alternative Democratic party in Colombia. Senator Robledo was first elected in 2002; he has been re-elected in consecutive periods, receiving more than 196,000 votes in the last election, being the most voted Senator in the last election. Additionally, several surveys have chosen him as one of the best Senators in Colombia.

Senator Robledo has a B.A. in Architecture from the Universidad de Los Andes and has served as Full-time Professor in the National University of Colombia for 26 years.

Last Sunday, in a decision that surprised many people, more than 6,400,000 Colombians voted against the approval of the Plebiscite on the Peace Agreements between the Government and the FARC. What does this mean for Colombia? What is next?

I believe these are very bad news. I supported the “Yes” campaign, and I believe the best thing would have been the triumph of the “Yes” vote. If the result would have been positive, today we would be starting the disarmament of the FARC and defining how those weapons would be destroyed.

Instead, we are in the middle of great uncertainty that could finish badly. We do not know.

However, it is also a fact that the “No” vote won. In these things, even though I supported the other option, I cannot change reality. The reality is that the “No” vote won.

Colombians would like to find a way to save this process and proceed to the disarmament of the FARC. Because last Sunday´s vote was not a vote supporting the war. It is unreasonable and difficult to understand outside of Colombia, but in Colombia, we were all in favor of FARC´s disarmament, even the FARC.

Some people in Colombia blamed the contents of the Agreement (judiciary benefits, political positions for the FARC). Others highlight the lack of solidarity from some cities and regions that are not too affected by the war. How do you make sense of the surprising result?

I have the impression, and it is an obviousness, that the “No” vote won because of the failure of the “Yes” vote to produce a national consensus to support the peace process. We were not able to build that consensus that brought us to a vote. So we were left in the worst of the worlds.

If, previously, an agreement between President Santos and former President Uribe would have been reached, we would not be today in this problem.

What do you do now? How do you reach this objective?

It is pretty unreasonable. Now everybody says that we should reach a national agreement, the one that was not possible before. And it is obvious. Because there is no solution to the crisis other than reaching that national agreement.

The thing is, that is not an easy task. I sent a letter, both to Uribe and Santos. I’ve told them: you have to reach an agreement, without your consensus there is no solution to this problem. The agreement also has to include FARC, because the FARC are the third leg of this table. If there is no solution, no advances, there is nothing we can do.

In electoral and political terms, why do you believe that more than 21 million registered voters did not participate in this referendum vote, even though it was such a key issue in the political development of Colombia?

In Colombia, we never have more than half the Colombians voting. That is the average in Colombia and in most of the world. People, for many reasons, do not vote. What happened here was that the abstention increased.

However, this was an expected effect because this election was atypical. Normally, the presidential elections have higher turnouts, and also the Parliamentary elections, because there are a lot of candidates and there is a lot of money moving around.

We all knew that, in this case, the abstention was going to be higher.

In general terms, regarding democracy, how do you analyze the increasing apathy of citizens all over the world about politics?

It is certainly not good. However, it is the reality that exists. I am not surprised by it, because all over the world people are resisting voting. The discredit of governments and the political class is huge. So, it is not strange to have so many skeptical people.

I am also not surprised, because in a world where things work out so badly everywhere, it is natural that certain groups react, as a way of protest, by saying: “do not count me in, we do not believe in anything anymore.”

If you had one measure that could improve the democratic process, what would you propose?

I would propose that governments and Parliaments stop deciding so badly. That is the root of the problem.

Beyond the current contingency, how would you qualify Colombia´s social, economic, and political situation?

Very bad. Not only because of the failure to approve the peace process, but because of something worse: Colombia´s economy is in a deep crisis. Growth rates have been decreasing; the level of external debt is too high; the deficit of the balance of payments is huge. The fiscal deficit is growing as well as the interest rate. In the end, we are in a very serious crisis that is getting worse.

Do you believe that if an agreement is reached there could be a brighter future for Colombia?

No, I do not believe so. It is always a positive thing to achieve peace and to begin the disarmament. However, all the studies say that there is not going to be a major impact in the economy that could correct our failing direction.

The government says that this is possible, but that is just propaganda.

Senator Jorge Robledo during a forum with students about the results of the vote on the peace agreements.

What is your opinion about Free Trade Agreements and different commerce alliances in general? In particular, what is your position on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the eventual incorporation of Colombia as a member, and also about the Pacific Alliance (where Colombia is a member with Chile, Peru, and Mexico)? Do you believe these agreements are positive for countries? or harmful for economies? Are there any alternatives to commercial openness?

When free trade agreements began in the ‘90s, some of us in Colombia and in the rest of the world voiced our opposition. For many years, this was a theoretical and abstract debate, because you could not foresee what was going to happen. Some people were in favor, others against.

However, nowadays the practical consequences can be observed. For countries like Colombia, this has been for us “as dogs in Mass” [ a popular saying in Colombia, reflecting how bad things have become for somebody]. With the United States, the free trade agreements have been especially a disaster.

The Pacific Alliance—a trade agreement with a different name—is going to cause further trouble. Even the business organizations in Colombia oppose the Pacific Alliance, and if we enter the TPP, the results will be even worse.

The problem with international trade is not to question their existence. The problem is that these agreements cannot be like “chickens and foxes” (another popular saying to highlight a very disadvantageous relationship).

Have you had the chance to follow the Presidential elections in the United States? To analyze the issues? In the context of Colombia, is the United States a relevant actor? What is the role of the future President of the United States in the development of Colombia or Latin America?

Colombia, as most of Latin America, is a country that relies heavily on the United States. Absolutely nothing gets done without US approval. The peace process, for example, would not have been possible without the permission of President Barack Obama.

The impact of everything that is happening in the United States is enormous. Although, I said this when Obama was elected and I repeat it again: too many illusions created. Today is worse, because there is no illusion at all.

President Obama was not going to change anything because his economic policies were the same ones promoted by President Bush. Globalization, open markets, transnationals. The military policy of President Obama is also the same as President Bush´s: the use of force by the US as a way to engage with the world.

In the current election, I do not believe that neither candidate is going to modify these policies. Both of them are part of the establishment.

A final question. In what ways, if any, has your past academic experience as a scholar helped you in your political career and within the political debate?

Yes, I was a full time professor at the National University of Colombia, in Manizales. I was there for a long time and was awarded several of the most important distinctions of the University. I was awarded the National Award in for Theory and Critical History in the field of Architecture. I have also published more than a dozens of books. So, anything positive I have done in Colombia´s National Congress is a result of my previous work. The pedagogic style in politics is very important, allowing [you] to explain better your positions. Also, the academic formation is essential to understand broad topics and prepare the issues. Being a professor has been of great help in my political career.

Senator Jorge Robledo answering questions during a forum with students at Cornell.