Introduction

On January 1, 1994, thousands of indigenous men and women in the southern state of Chiapas, Mexico, who identified themselves as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), declared war on the Mexican government. The Zapatistas considered themselves the product of 500 years of struggle against Spanish colonization, North American imperialism, and Mexican authoritarianism. Their motto was: “Today, we say enough.” It was no accident that the uprising took place the same day the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, either. The Zapatistas were rebelling against the free market model enshrined in NAFTA and the national policies that promoted economic liberalization for Mexico, including the privatization of community-owned lands.[1]

Indigenous communities tend to live in the most marginalized and remote regions of Mexico. They are known for their high levels of poverty and lack of access to public services, such as health care and education. In 2012, the National Council for Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) estimated that 78.6 percent of people who speak an indigenous language live in poverty compared to 43 percent of people who do not speak an indigenous language.[2] The Zapatista struggle was a direct result of these conditions, bringing worldwide attention to the problems of Mexico’s indigenous population. Their uprising was part of a historic struggle for land rights, human rights, political autonomy, cultural recognition, and the rights to self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance.[3]

Indigenous peoples in Mexico have historically fought to preserve their own traditional forms of organization and local governance. Since the uprising of 1994, the Mexican government has made political concessions, starting with the San Andrés Accords of 1996, which granted indigenous peoples a political voice in local governments.[4] The greatest concession, however, came on August 14, 2001, when the Mexican government reformed Article 2 of the Constitution of Mexico, recognizing indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance. Today, indigenous communities in Mexico are entitled to apply their own legal systems and to elect their authorities in accordance with their communitarian rules, practices, and traditions.[5]

Nevertheless, not all the members of indigenous communities benefited equally from the application of communitarian laws and practices. In fact, indigenous women have been discriminated against pursuant to communitarian laws and practices of the indigenous communities. For instance, in nearly a quarter of municipalities in Oaxaca with communitarian legal systems, women were not permitted to participate in local assemblies, nor were they allowed to be elected as municipal authorities. By 2008, only three women had been elected as municipal presidents in these municipalities.[6] The Mexican government failed to understand the distinct forms of discrimination and disadvantage that can occur as a consequence of the intersections of indigenous women’s identities such as their gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and education level. The constitutional reform that recognized indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance had unintended consequences, including human rights violations against indigenous women, which will be examined in the following paragraphs applying Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera’s Systems Thinking theory.

Four Simple Rules for Policymaking

In Systems Thinking Made Simple, Derek and Laura Cabrera explain four simple rules―Distinctions, Systems, Relationships and Perspectives―that underlie systems thinking and that are summarized by the acronym “DSRP.” First, the “Distinction Rule” states that any idea or thing can be distinguished from other ideas or things. Second, the “Systems Rule” stipulates that any idea or thing can be split into parts or lumped into a whole. Third, the “Relationship Rule” says that any idea or thing can relate to other things or ideas. Fourth, the “Perspective Rule” postulates that any thing or idea can be the point or the view of a perspective. According to the Cabreras, “a point is the idea/thing that is looking or focusing, while a view is the idea/thing that is being looked at or focused upon.” These four rules do not operate linearly, but simultaneously. A thing or idea can simultaneously be a distinct entity, a perspective, a part of a larger whole, a whole made up of smaller parts, and a relationship.[7]

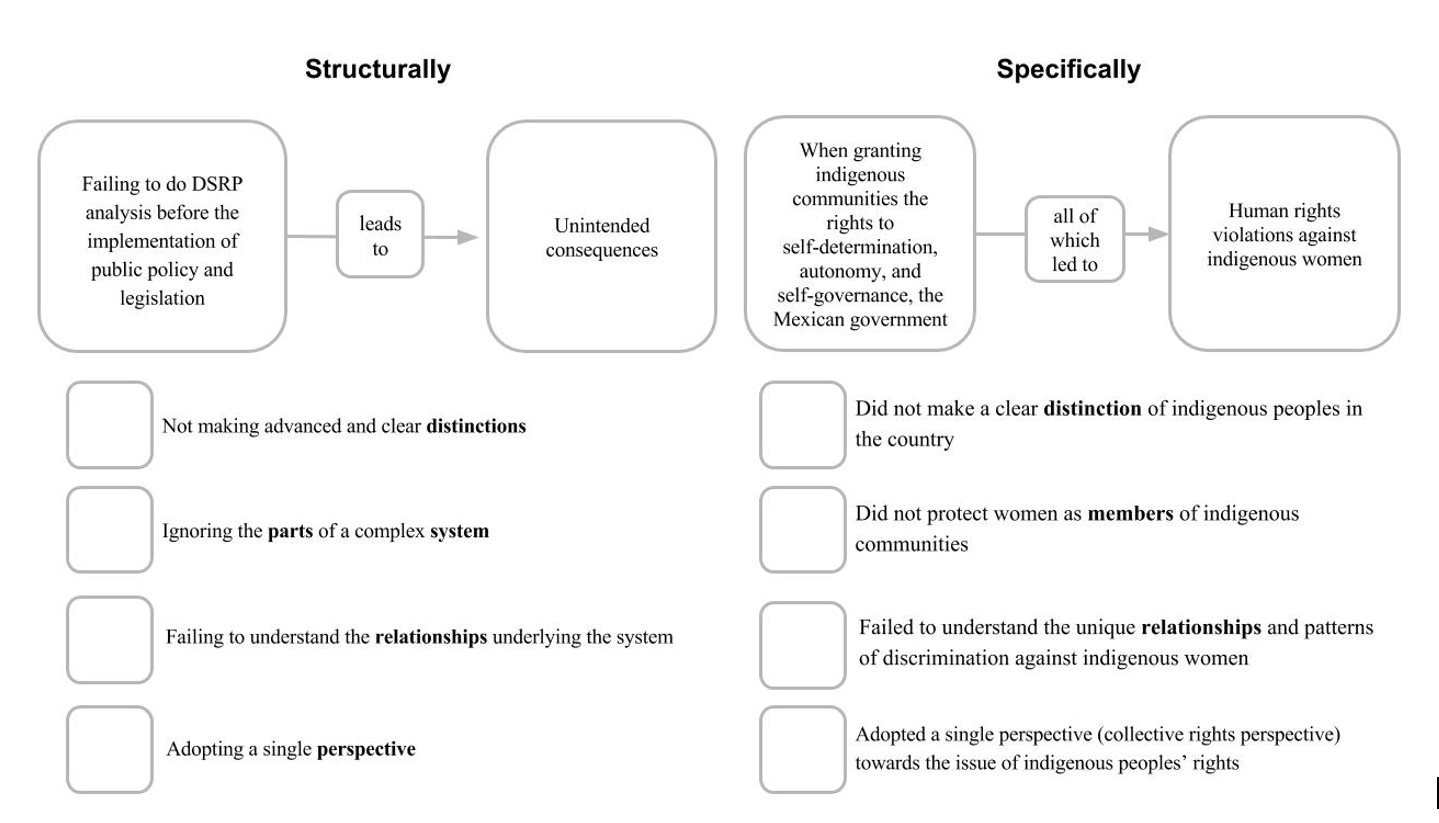

This article uses DSRP structural analysis to show that failing to 1) make advanced and clear distinctions, 2) identify the parts of a complex system, 3) understand the relationships underlying the system, and 4) adopt different perspectives before the implementation of public policy and legislation can lead to unintended consequences that are harmful for some social groups. When granting indigenous communities in Mexico the rights to self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance, the Mexican government failed to make a clear distinction of indigenous peoples in the country, protect indigenous women as members of indigenous communities, understand the unique relationships and patterns of discrimination experienced by indigenous women, and adopt different perspectives towards the issue of indigenous peoples’ rights. These failures have led to human rights violations against indigenous women.

Figure 1.

The MetaMap below shows the structural analysis of this case based on Derek and Laura Cabrera’s Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives Rules. The MetaMap on the right shows the specific information that is being analyzed, which is the complex issues of indigenous peoples’ rights in Mexico.

Distinction Problem: Who Are Indigenous Peoples in Mexico?

There is no universally accepted definition of “indigenous peoples.” In fact, every country and organization has its own definition of indigenous peoples, usually based on some of the following criteria: “self-identification, historical continuity with pre-colonial societies, strong link to territories and resources, distinct social, economic and political systems, distinct language, culture and beliefs, and a resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities.”[8] According to Article 2 of the Constitution of Mexico, indigenous peoples are:

[…] those who have descended from the people who inhabited the present territory of the country at the beginning of the colonization and who have preserved at least in part their own social, economic, cultural, and political institutions. The awareness of their indigenous identity shall be an essential criterion for determining to whom the provisions on indigenous peoples apply. Communities of indigenous people are those which constitute a social, economic, and cultural unit, are situated in a territory, and have their own authorities in accordance with their traditions and customs.[9]

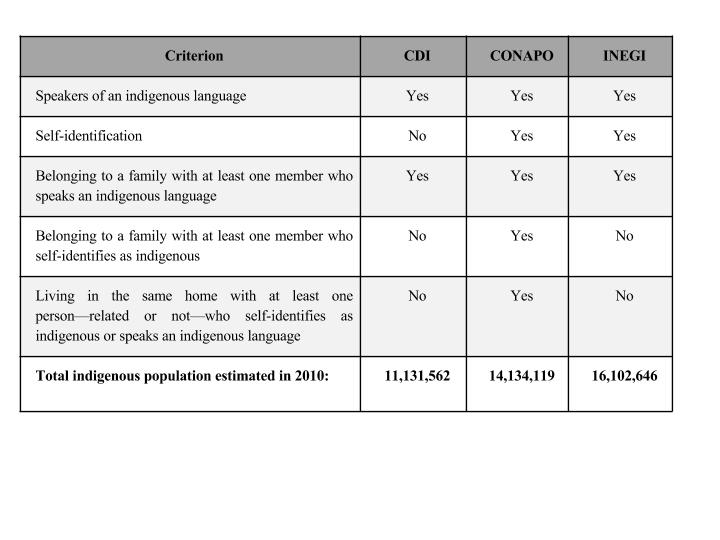

In Mexico, three federal institutions measure and monitor the country’s indigenous population: the National Population Council (CONAPO), the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Groups (CDI), and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). Each of these institutions utilizes different criteria to estimate Mexico’s indigenous population. Table 1 shows the criteria considered by each institution to estimate the country’s indigenous population based on the 2010 Population and Housing Census.[10]

Table 1. Estimates of Mexico’s Indigenous Population for 2010

Source: Elaborated by the author based on information from Juan Cristobal Rubio Badán, “Censos y Población Indígena en México: Algunas Reflexiones,” Series de La Cepal (Sede Subregional de la CEPAL en México, July 2014), http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/36858/1/S1420252_es.pdf.

According to a population survey conducted in 2015 by INEGI, 21.5 percent of the total population in Mexico—equivalent to 25.6 million people, 13.2 million of whom are women—defines itself as indigenous. Six percent of the population—equivalent to 7.4 million people, 3.8 million of whom are women—speaks an indigenous language.[11] In the same year, the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Groups estimated that there are 12.2 million indigenous people in Mexico, 6.1 million of whom are women.[12] These figures show that the number of indigenous people in the country depends on the definition of indigenousness that the government and other institutions decide to adopt.

The lack of a homologized method for defining and measuring Mexico’s indigenous population raises several policy and jurisdictional issues that must be further explored. For instance, how can the government, or any other organization, protect the rights of indigenous peoples without a clear idea of who they are? How can Article 2 of the Mexican Constitution—which grants the rights of self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance to indigenous peoples—be exercised effectively if there is not a clear definition of indigenous peoples? These questions fall outside the scope of this article, although they show how indigenous peoples have been sidelined from the public agenda.

If policymakers ignore distinction analysis, their policies will generate numerous unintended consequences without necessarily benefiting the intended population. Distinction analysis must consider the criteria underlying the distinction, its boundaries, its biases, and its limitations (what the distinction is not). This will help to identify those identities that might have been overlooked or marginalized.[13] The Mexican government clearly needs to conduct distinction analysis of its indigenous population.

Ignoring the Parts of a Complex System: What About Indigenous Women’s Rights?

The reform of Article 2 of the Constitution of Mexico was a great triumph for indigenous peoples in the country. Before 2001, Article 2 of the Constitution of Mexico did not recognize indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance. After the reform, Article 2 recognized these rights, so that indigenous communities can:

- Decide their internal forms of coexistence, as well their social, economic, political, and cultural organization.

- Apply their own standards in regulation and solution of their internal conflicts, subject to the general principles of the Constitution, respecting individual guarantees, human rights, and, in a relevant manner, the dignity and completeness of women.

- Elect, in accordance with their traditional standards, procedures, and practices, authorities or representatives for the exercise of their own forms of internal government, guaranteeing the participation of women in conditions of equality to those of men, in a way that respects the Federal Pact and the sovereignty of the states.[14]

Nevertheless, in many indigenous communities of Mexico, cultural values and communitarian laws confer a marginal role to women in decision-making processes and resource use. Women are excluded from participating in community assemblies or do so without the right to vote.[15] As mentioned earlier, indigenous women’s rights have been violated pursuant to indigenous customary law, rules, and practices. The case of Adriana Manzanares, an indigenous woman from the Mexican state of Guerrero, is emblematic of the consequences of failing to protect indigenous women both within and outside their indigenous communities.

In 2006, at the age of 20, Adriana became pregnant for the third time. The father of her child was not her husband, who years earlier had migrated to the United States. Adriana suffered a miscarriage. She was accused of adultery and abortion by her father before a communitarian assembly, and the assembly sentenced her to be stoned and humiliated in public pursuant to communitarian rules. After the public shaming, Adriana was taken to the Public Prosecutor of Guerrero, where she was convicted for the crime of murder and sentenced to 22 years in prison. She only spoke Tlapaneco, an indigenous language, and her trial was not translated from Spanish to Tlapaneco. After spending 7 years in prison, Adriana was finally released by a ruling from the Mexican National Supreme Court, which concluded that her procedural rights were violated from the beginning of the investigation.[16]

Another emblematic case of indigenous women’s rights violations due to the application of communitarian laws is the case of Eufrosina Cruz Mendoza. Of the 570 municipalities in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, 418 are governed by communitarian practices that prohibit women to be voted in municipal elections.[17] Eufrosina was born in Santa María Quiegolani, a Zapotec community in Oaxaca. Eufrosina left her home when she was twelve years old and went to school in Oaxaca, the state’s capital city. She returned to her hometown after working as a teacher for several years, and she decided to run for mayor in 2007. After she won the election, the local municipal council, which consisted entirely of men, ordered that the votes cast for Eufrosina be disregarded. She appealed the decision before the local electoral council with no success. According to this local governing body, women were not allowed to hold public office pursuant to communitarian rules.[18]

After she was prevented from taking office at the municipal level, Eufrosina decided to run for office as a representative of Oaxaca’s State Congress. She was elected chairwoman of the State Congress, and in 2012 she won a seat in the Mexican National Congress.[19] At the federal and state levels, women’s right to be elected to public office is legally protected by the Constitution and by all international human rights treaties ratified by Mexico. At the municipal level, however, gender equality and indigenous customary law tend to collide.

Fortunately, change is already taking place in Mexico thanks to the political, legal, and personal struggles of women like Eufrosina and Adriana, who have championed indigenous women’s rights in the country. Prior to 2015, Article 2 of the Constitution of Mexico specified that indigenous communities had to apply their traditional standards, procedures, and practices “respecting individual guarantees, human rights, and, in a relevant manner, the dignity and completeness of women […]” as well as “[…] guaranteeing the participation of women in conditions of equality to those of men.”[20] The vagueness of this language allowed different interpretations of how to guarantee the “participation of women in conditions of equality.” Most indigenous communities in Mexico granted women the right to vote, but not the right to be elected as authorities of their communities.

In an attempt to improve women’s status within indigenous communities, in 2015 the Mexican government reformed Article 2 again to explicitly recognize indigenous women’s right “to vote and being voted under equitable condition as men; as well as to guarantee the access to public office or elected positions to those citizens that have been elected or designated within a framework that respects the federal pact and the sovereignty of the states. In no case the communitarian practices shall limit the electoral or political rights of the citizens in the election of their municipal authorities.”[21] Today, women in Eufrosina’s community can vote and hold seats on the city council.

The cases of Adriana Manzanares and Eufrosina Cruz are examples of how the Mexican government’s failure to safeguard the individual rights of women affected by discriminatory local practices further enabled indigenous women’s rights violations under communitarian laws. Policies that disregard the parts of a complex system—for example, the roles indigenous women play in their communities—can have negative consequences. They are in strict contradiction to the second rule of DSRP—the “Systems Rule.” If policymakers ignore the constitutive parts of systems they are trying to influence, their public policies will produce numerous unintended consequences.

Failing to Understand the Relationships Underlying the System: Why Do Indigenous Women Experience Particular Forms of Discrimination?

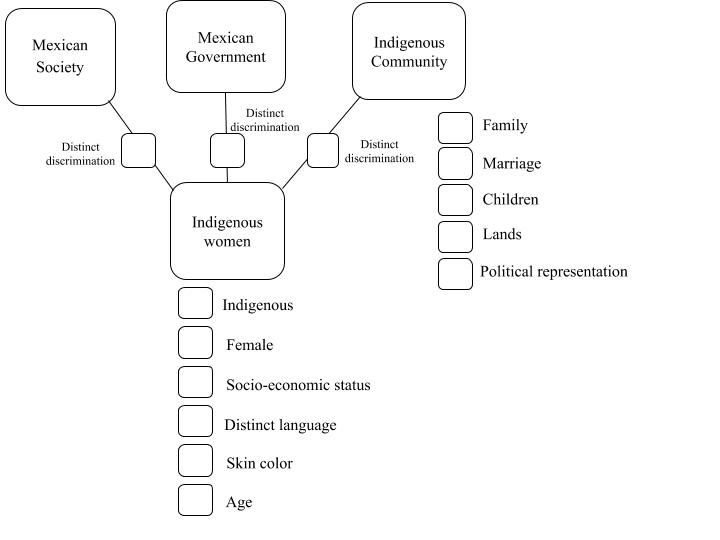

Kimberlé Crenshaw, Professor at Columbia Law School and the University of California, Los Angeles, who coined the term intersectionality and laid the groundwork for the concept, explains that intersectionality is about how institutions make certain identities the means for vulnerability.[22] Analysis that attends to intersectionality pays special attention to the experiences of persons who exist at the intersection of more than one identity and who may, because of those multiple identities, face a distinct, sometimes unique, form of discrimination.[23] For example, the intersection of gender with other factors—including race, ethnicity, culture, language, religion, and socioeconomic class—gives rise to the particular forms of discrimination and human rights violations that indigenous women experience. Indigenous women could also often encounter distinct forms of discrimination because of their age, marital status, occupation, sexual preference, education level, and health.[24]

Indigenous women experience inequalities beyond those experienced by non-indigenous women and by their male counterparts. For instance, on average, indigenous women in Mexico attend school for 5.1 years, which is less than the average school attendance of non-indigenous women and indigenous men (9 years and 6.2 years, respectively).[25] Therefore, the rights to equality and non-discrimination attempt to address disparities between non-indigenous and indigenous peoples as well as between indigenous women and indigenous men.[26]

The specific experiences of indigenous women show that failing to integrate intersectionality into law and policy formulation contributes to the exclusion and marginalization of certain people in society—as is apparent in the case of Adriana Manzanares. First, she was stoned and humiliated by members of her indigenous community, pursuant to communitarian laws and practices. Second, she was convicted for the crime of murder pursuant to state law in Guerrero, where abortion is considered a crime. Third, she was convicted without being able to defend herself because she did not speak Spanish and her defense was not translated. The fact that Adriana is an underprivileged woman and an indigenous person who, at the time of her conviction, did not speak Spanish gave rise to the distinct forms of discrimination that she experienced.

Derek and Laura Cabrera’s “Relationship Rule” can help policymakers expose the different types of discrimination and disadvantage that can occur as a consequence of people’s intersecting identities. Recognizing social and institutional relationships is useful to assess the impact of public policies on people’s access to rights and opportunities, and this kind of analysis shows how policies and laws that impact on one aspect of life are inextricably linked to others.[27] Relationship-focused analysis requires to focus on linkages, points of intersection, processes, and social contexts rather than on defined situations and isolated issue areas. Intersectionality and relationship analysis are consistent with the principles of international law: all human rights are universal, indivisible, interdependent, and interrelated.[28] Just as there are no human rights without women’s rights, there are no human rights that do not involve the rights of indigenous peoples, the rights of people with disabilities, and the rights of LGBTQI people, to name a few.[29] Any approach aimed at protecting indigenous women must incorporate both individual rights and collective rights such as the right to live free from violence and the right to self-determination.[30]

Figure 2. This MetaMap shows the different relationships that shape indigenous women’s lives.

Adopting a Single Perspective: Where Are the Voices of Indigenous Women?

The “Perspective Rule” postulates that any thing or idea can be the point or the view of a perspective. The Mexican government’s approach to the issue of indigenous peoples’ rights can also be analyzed in terms of the perspectives that were taken, and of those not taken, in order to address the problem. The Mexican Government failed to consider multiple perspectives when recognizing indigenous peoples’ collective rights, which exacerbated the hindrances for indigenous women in exercising their individual rights as members of their communities.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) affirms that “indigenous peoples are equal to all other peoples, while recognizing the right of all peoples to be different, to consider themselves different, and to be respected as such.” UNDRIP also recognizes that “indigenous peoples possess collective rights which are indispensable for their existence, well-being and integral development as peoples.” For years it has been argued, both in Mexico and across the world, that an exclusive emphasis on individual rights cannot effectively recognize and protect the rights and freedoms of indigenous peoples, who require protection as collectivities in order to survive and flourish as distinct peoples and cultures.[31] As the International Indigenous Women’s Forum affirmed in its Beijing + 10 Declaration, the interrelatedness of individual and collective rights is fundamental in the experiences of indigenous women. Their declaration states:

We maintain that the advancement of Indigenous Women’s human rights is inextricably linked to the struggle to protect, respect, and fulfill both the rights of our Peoples as a whole and our rights as women within our communities and at the national and international level.

The main idea underlying collective rights is that they are fundamental in protecting members of a group from discrimination by the larger society. Collective rights are usually justified as means to the collective recognition and self-governance of the group to which they are given. This account, however, justifies them only insofar the collective self-rule of the group furthers the individual autonomy of its members.[32]

As mentioned earlier, however, indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance in Mexico have sometimes led to abuse, within the group, of its female members. Mexico’s approach to protecting indigenous communities as distinct peoples and cultures still lacks fundamental protections that specifically address women’s positions as individual members of indigenous communities. The Mexican government should implement policy and legislation that simultaneously protect indigenous communities as collective groups and also protect the rights of indigenous women as individuals within these communities. In other words, different perspectives towards indigenous peoples’ rights need to be taken into consideration to balance collective rights against indigenous women’s individual rights.

Furthermore, indigenous rights, as all other human rights, should not be applied to a gender-neutral lens. Public policies impact men and women in different ways. A gender perspective is vital to protect indigenous women’s rights. Indigenous women need to have a voice in decision-making processes, in the management of resources, and in the representation of their groups. In the same way that gender-discriminatory practices are debated and questioned in other communities, they should be debated and questioned in indigenous ones.

The right to self-determination, along with the right to free, prior, and informed consent and the right to participate in decision-making, should be a foundational principle to recognize and respect the political and legal systems of indigenous peoples. The right of indigenous women to participate in decision-making processes is critical to the development, implementation, and evaluation of policy and legislation affecting them. Indigenous women’s individual rights can be protected if self-determining indigenous communities are accountable to act in a manner that is respectful of human rights norms, including equality and non-discrimination.[33]

Cultivating an awareness of the perspectives we take or reject is crucial to approaching specific problems with clarity and comprehension. A shift in perspective can transform the distinctions, relationships, and systems that policymakers see and do not see. Moreover, perspectives are vital to see the world from the advantage or disadvantage of other people.[34] If policymakers ignore the multiple perspectives that can shape analysis of social issues, their policies and legislation will have highly inequitable and unexpected outcomes.

The Continuous Adaptation of Mental Models

Derek and Laura Cabrera explain that a mental model is our understanding of the world based upon our own ideas, beliefs, and past experiences. We perceive the real world indirectly through mental models that in turn shape our behavior, generating real-life consequences. They argue that “wicked problems result from the mismatch between how real-world systems work and how we think they work.”[35] Thus it is fundamental for policymakers, and systems-thinkers in general, to constantly analyze the feedback that the real world is sending and to adapt their mental models accordingly. It took fourteen years for the Mexican government to explicitly recognize indigenous women’s right to be elected as authorities in their communities. This, of course, is not the final solution to the trade-off between indigenous women’s individual rights and indigenous communities’ collective rights, but it is a first step in adapting a previously held mental model.

The goal of systems thinking is the continuous adjustment and refinement of our mental models so that they more accurately reflect the real world.[36] By considering four simple patterns—the Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives Rules—policymakers can analyze real world phenomena and adjust their mental models accordingly. The more closely a mental model approximates reality, the more effective will be any public policies crafted according to that model.[37]

The application of DSRP analysis to policy and legislation aimed at indigenous communities in Mexico will lead to the protection of the human rights of both indigenous men and women. In particular, the Mexican government should:

- Make a clear distinction of indigenous peoples in the country and collect sex-disaggregated data.

- Implement affirmative action measures to empower women as members of indigenous communities and give them access to education, healthcare, lands, decision-making processes, and resources.

- Apply intersectional analysis and measures that take into consideration the unique relationships that shape indigenous women’s lives.

- Incorporate a gender perspective into the policy and legislation aimed at indigenous peoples.

Policymakers need to start looking at both the identity and the other when making distinctions, understanding that we are all part of a larger interrelated system, recognizing the underlying relationships, contexts, and the fact that their actions have effects on other people, and seeing things from other people’s perspectives. If they achieve to apply the four simple rules of DSRP, policymakers will become more prosocial, emotionally intelligent, and compassionate leaders.[38] Let us hope that policymakers start using DSRP as a tool to better approximate their mental models to reality and to create effective, complex, dynamic, and multivalent policies.

References

- Jesús Antonio Machuca, “La Democracia Radical: Originalidad Y Actualidad Política Del Zapatismo de Fin Del Siglo XX,” in El Zapatismo Y La Política (Plaza y Valdés Editores, 1998). ↑

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, “La Pobreza de La Población Indígena En México 2012” (México D.F: CONEVAL, 2014), 12, http://www.coneval.org.mx/Informes/Coordinacion/INFORMES_Y_PUBLICACIONES_PDF/POBREZA_POBLACION_INDIGENA_2012.pdf. ↑

- Machuca, “La Democracia Radical: Originalidad Y Actualidad Política Del Zapatismo de Fin Del Siglo XX.” ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- CDPIM, “Reformas Constitucionales sobre Derechos y Cultura Indígenas Publicado en el Diario Oficial el 14 de agosto de 2001” (Comisión para el Diálogo con los Pueblos Indígenas de México, 2012), http://www.cdpim.gob.mx/v4/02_normativa_reformas.html. ↑

- Rachel Sieder, “Legal Pluralism and Indigenous Women’s Rights in Mexico: The Ambiguities of Recognition Symposium: Twenty First Annual Herbert Rubin and Justice Rose Luttan Rubin International Law Symposium: Constitution and Custom: Women’s Rights and Access to Justice in Pluralist Society,” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 48 (2016 2015): 1125–50. ↑

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems (Ithaca, New York: Odyssean Press, 2015), 45. ↑

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, “Who Are Indigenous Peoples?,” n.d., http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf. ↑

- Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos [Constitution], as amended, Diario Oficial de la Federación [D.O.], art.2, 14 de agosto de 2001. ↑

- In Mexico population censuses are conducted every 10 years. The next census will be in 2020. ↑

- INEGI, “Encuesta Intercensal 2015” (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2015), http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/encuestas/hogares/especiales/ei2015/doc/eic_2015_presentacion.pdf. ↑

- Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, “Indicadores Sobre Las Mujeres Indígenas. Resultados de La Encuesta Intercensal 2015,” March 2017, http://www.gob.mx/cdi/articulos/indicadores-sobre-las-mujeres-indigenas-resultados-de-la-encuesta-intercensal-2015?idiom=es. ↑

- Cabrera and Cabrera, Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. ↑

- Constitution, as amended, Diario Oficial de la Federación [D.O.], art.2, 14 de agosto de 2001. ↑

- Michael Stephen Danielson, Todd Alan Eisenstadt, and Jennifer Yelle, “Ethnic Identity, Informal Institutions, and the Failure to Elect Women in Indigenous Southern Mexico,” Journal of Politics in Latin America 5, no. 3 (December 10, 2013): 3–33. ↑

- “Corte Resolverá Caso de Mujer Indígena Tlapaneca,” Excélsior, January 22, 2014, http://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/2014/01/22/939657; “Corte Analizará Caso de Indígena Presa Por Aborto,” Animal Político, January 21, 2014, http://www.animalpolitico.com/2014/01/suprema-corte-analizara-manana-caso-de-indigena-presa-por-aborto/; Jesús Aranda, “Liberan a Indígena Guerrerense Encarcelada 7 Años Por Abortar,” La Jornada, January 23, 2014. ↑

- Danielson, Eisenstadt, and Yelle, “Ethnic Identity, Informal Institutions, and the Failure to Elect Women in Indigenous Southern Mexico.” ↑

- Ediciones El País, “La rebelión se llama Eufrosina Cruz,” EL PAÍS, February 10, 2008, http://elpais.com/diario/2008/02/10/internacional/1202598001_850215.html. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Constitution, as amended, Diario Oficial de la Federación [D.O.], art.2, 14 de agosto de 2001 (Mex.). ↑

- Constitution, as amended, Diario Oficial de la Federación [D.O.], art.2, 22 de mayo de 2015 (Mex.). ↑

- Southbank Centre, Kimberlé Crenshaw – On Intersectionality – Keynote – WOW 2016, accessed April 17, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DW4HLgYPlA. ↑

- Aisha Nicole Davis, “Intersectionality and International Law: Recognizing Complex Identities on the Global Stage Student Note,” Harvard Human Rights Journal 28 (2015): 205–42. ↑

- Helen Tugendhat and Tebtebba (Organization), Realizing Indigenous Women’s Rights : A Handbook on the CEDAW (Baguio City, Philippines: Tebtebba Foundation, 2013), 41, http://newcatalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/9663638. ↑

- INEGI, “Encuesta Intercensal 2015.” ↑

- M. Céleste McKay, “International Human Rights Standards and Instruments Relevant to Indigenous Women,” Canadian Woman Studies; Downsview 26, no. 3/4 (Winter/Spring 2008): 147–153,14. ↑

- Alison Symington, “Intersectionality: A Tool for Gender and Economic Justice,” Women’s Rights and Economic Change (Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), August 2004), 2. ↑

- Realizing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : Triumph, Hope, and Action (Saskatoon: Purich Pub., 2010), 159, http://newcatalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/7010357. ↑

- Symington, “Intersectionality: A Tool for Gender and Economic Justice.” ↑

- McKay, “International Human Rights Standards and Instruments Relevant to Indigenous Women.” ↑

- Alexandra Xanthaki, “Collective Rights: The Case of Indigenous Peoples,” Amicus Curiae, no. 25 (March 2000): 7–11. ↑

- Maria Noel Leoni Zardo, “Gender Equality and Indigenous Peoples’ Right to Self-Determination and Culture,” American University International Law Review 28, no. 4 (2013): 1053–90. ↑

- McKay, “International Human Rights Standards and Instruments Relevant to Indigenous Women.” ↑

- Cabrera and Cabrera, Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems, 183. ↑

- Ibid., 33. ↑

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, ‘Systems Thinking Card Set’, Google Docs, December 2016, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9g854J1dTGYY0Rqc3RFTndIcmM/view?usp=sharing&usp=embed_facebook. ↑

- Cabrera and Cabrera, Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

Bibliography

Aranda, Jesús. “Liberan a Indígena Guerrerense Encarcelada 7 Años Por Abortar.” La Jornada. January 23, 2014.

Cabrera, Derek, and Laura Cabrera. Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. Ithaca, New York: Odyssean Press, 2015.

CDPIM. “Reformas Constitucionales sobre Derechos y Cultura Indígenas Publicado en el Diario Oficial el 14 de agosto de 2001.” Comisión para el Diálogo con los Pueblos Indígenas de México, 2012. http://www.cdpim.gob.mx/v4/02_normativa_reformas.html.

Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. “Indicadores Sobre Las Mujeres Indígenas. Resultados de La Encuesta Intercensal 2015,” March 2017. http://www.gob.mx/cdi/articulos/indicadores-sobre-las-mujeres-indigenas-resultados-de-la-encuesta-intercensal-2015?idiom=es.

Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social. “La Pobreza de La Población Indígena En México 2012.” México D.F: CONEVAL, 2014. http://www.coneval.org.mx/Informes/Coordinacion/INFORMES_Y_PUBLICACIONES_PDF/POBREZA_POBLACION_INDIGENA_2012.pdf.

“Corte Analizará Caso de Indígena Presa Por Aborto.” Animal Político, January 21, 2014. http://www.animalpolitico.com/2014/01/suprema-corte-analizara-manana-caso-de-indigena-presa-por-aborto/.

“Corte Resolverá Caso de Mujer Indígena Tlapaneca.” Excélsior, January 22, 2014. http://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/2014/01/22/939657.

Danielson, Michael Stephen, Todd Alan Eisenstadt, and Jennifer Yelle. “Ethnic Identity, Informal Institutions, and the Failure to Elect Women in Indigenous Southern Mexico.” Journal of Politics in Latin America 5, no. 3 (December 10, 2013): 3–33.

Davis, Aisha Nicole. “Intersectionality and International Law: Recognizing Complex Identities on the Global Stage Student Note.” Harvard Human Rights Journal 28 (2015): 205–42.

INEGI. “Encuesta Intercensal 2015.” Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2015. http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/encuestas/hogares/especiales/ei2015/doc/eic_2015_presentacion.pdf.

Machuca, Jesús Antonio. “La Democracia Radical: Originalidad Y Actualidad Política Del Zapatismo de Fin Del Siglo XX.” In El Zapatismo Y La Política. Plaza y Valdés Editores, 1998.

McKay, M. Céleste. “International Human Rights Standards and Instruments Relevant to Indigenous Women.” Canadian Woman Studies; Downsview 26, no. 3/4 (Winter/Spring 2008): 147–153,14.

País, Ediciones El. “La rebelión se llama Eufrosina Cruz.” EL PAÍS, February 10, 2008. http://elpais.com/diario/2008/02/10/internacional/1202598001_850215.html.

Realizing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : Triumph, Hope, and Action. Saskatoon: Purich Pub., 2010. http://newcatalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/7010357.

Sieder, Rachel. “Legal Pluralism and Indigenous Women’s Rights in Mexico: The Ambiguities of Recognition Symposium: Twenty First Annual Herbert Rubin and Justice Rose Luttan Rubin International Law Symposium: Constitution and Custom: Women’s Rights and Access to Justice in Pluralist Society.” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 48 (2016 2015): 1125–50.

Southbank Centre. Kimberlé Crenshaw – On Intersectionality – Keynote – WOW 2016. Accessed April 17, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DW4HLgYPlA.

Symington, Alison. “Intersectionality: A Tool for Gender and Economic Justice.” Women’s Rights and Economic Change. Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), August 2004.

Tugendhat, Helen, and Tebtebba (Organization). Realizing Indigenous Women’s Rights : A Handbook on the CEDAW. Baguio City, Philippines: Tebtebba Foundation, 2013. http://newcatalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/9663638.

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. “Who Are Indigenous Peoples?,” n.d. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf.

Xanthaki, Alexandra. “Collective Rights: The Case of Indigenous Peoples.” Amicus Curiae, no. 25 (March 2000): 7–11.

Zardo, Maria Noel Leoni. “Gender Equality and Indigenous Peoples’ Right to Self-Determination and Culture.” American University International Law Review 28, no. 4 (2013): 1053–90.