Introduction

In the United States, the issue of abortion remains contentious today, despite the Supreme Court decision that legalized the procedure more than forty years ago. Since that 1973 decision, abortion has become a largely political topic; individual states have enacted laws that restrict women’s ability to obtain an abortion by varying degrees, and abortion has been a prominent topic during political elections. In the 2016 election cycle, the topic of abortion surfaced in the Presidential and the Vice Presidential debates, as well as many congressional and gubernatorial races. Candidates label themselves based on their abortion stance, and many voters may choose a candidate explicitly because of that stance.

Until 1973, laws regulating abortions were left up to the states, and many chose to enact regulations that banned the practice. The majority of these laws targeted those performing the abortions, rather than the women themselves. Prior to 1973, the resultant fear of losing their medical licenses and facing criminal charges meant that few doctors were willing to perform abortions. By the late 1960s, social pressures and the feminist movement pushed states to begin to relax these laws; by 1970, 16 states had created new regulations that allowed women access to legal abortions. In early 1973, the United States Supreme Court heard two cases: Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton; on January 22, 1973, the Court ruled that the 14th amendment protected a woman’s right to have an abortion under the Due Process Clause and its interpreted right to privacy. This case forms the basis for all abortion regulations in the United States today.[4]

Background: Roe v. Wade (1973) and Subsequent Supreme Court Rulings

“No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” – 14th Amendment[5]

In 1971, “Jane Roe,” a single woman who lived in the state of Texas, became pregnant and wished to obtain an abortion; however, her home state of Texas criminalized all abortions unless the procedure was to terminate a pregnancy resulting from rape or incest, or the pregnancy would cause undue harm to the mother.[6] Roe challenged the Texas law to obtain a legal abortion on the basis of her 14th amendment right to privacy. The case started in the Texas court system and was eventually appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1973. As mentioned above, Roe v. Wade became the landmark case that determined that women have the Constitutional right to seek an abortion before a fetus is viable, or able to survive outside the womb.[7] According to the ruling, the right to privacy described in the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment protects a woman’s decision to terminate or continue a pregnancy.

“State criminal abortion laws, like those involved here, that except from criminality only a life-saving procedure on the mother’s behalf without regard to the stage of her pregnancy and other interests involved violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects against state action the right to privacy, including a woman’s qualified right to terminate her pregnancy.” – Roe v. Wade (1973)[8]

A companion case, Doe v. Bolton, was decided in tandem; this court decision stated that abortions could be performed after viability under a health exception. If the “physical, emotional, psychological, familial… well-being of the patient” is endangered by carrying the fetus to term, the court ruled, it is legal to obtain an abortion to preserve the life or health of the mother.

Figure 1: Women on both sides of the issue stand at a rally.

The Aftermath of Roe v. Wade (1973)

The immediate response to Roe v. Wade came in the form of the enactment of a number of state laws that limited access to abortions, as well as several court cases regarding the constitutionality of these laws. In 1976, for example, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Planned Parenthood v. Danforth overturned a Missouri law requiring spousal consent for an abortion.

Congress also enacted several provisions that limited access to abortions: in 1977, for example, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment as part of the renewal of the Social Securities Act. This amendment restricted public Medicaid funding from being used for abortion unless the pregnancy endangered the woman’s life or was the result of rape or incest. This amendment was upheld by the Supreme Court in Harris v. McCrae (1980).

Similar to the decision regarding the Hyde Amendment, in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989) the Court ruled that states were allowed to ban the use of public employees and facilities for abortions. This case also challenged the definition of viability put forth in Roe v. Wade, and allowed states to require doctors to start testing for viability at 24 weeks, rather than the original 28 weeks.

In 1992, the Court overturned some of its previous provision in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern PA v. Casey. This case modified the definition of viability and allowed states to regulate abortion practices before fetal viability. It also created a provision that, despite their newfound control over early abortion practices, states could not cause “undue burden” with their regulations.

“A statute which while furthering [a] valid state interest, has the effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman’s choice cannot be considered a permissible means of serving its legitimate end…Unnecessary health regulations that have the purpose or effect of presenting a substantial obstacle to a woman seeking an abortion impose an undue burden on the right” – Planned Parenthood of Southeastern PA. v. Casey (1992)[9]

The ruling in Casey affected both sides of the abortion debate: it allowed states whose governing bodies disagreed with federal abortion regulations the power to enact limited modifications, while still protecting a woman’s right to choose.

In 2000, the Supreme Court heard Sternberg v. Carhart, in which a physician challenged the constitutionality of Nebraska’s ban on partial-birth abortions—a practice in which the fetus is extracted from the uterus and then terminated[10] The court ruled that banning this practice placed undue burdens on both physicians and women, as the law did not have a health exception. In order to comply with the rulings of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the ruling held, it is necessary that there be no undue burdens and that states have provisions that protect the woman’s health. This ruling struck down similar laws in 30 states around the country.

In 2003, Congress passed the Federal Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act, which created a national ban of the procedure. When the law was challenged in 2007 in Gonzales v. Carhart, the Supreme Court reversed its Sternberg decision, stating that the federal ban of the procedure was different from the Nebraska law challenged in 2000. In the wake of this decision, many states recognized that the Supreme Court had left room for more state restrictions to be enacted.[11]

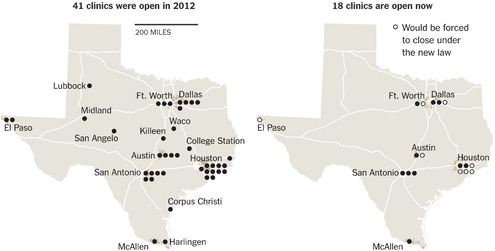

The most recent Supreme Court decision regarding abortion occurred in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt in 2015. This court case challenged Texas law HB2, which required that all Texas facilities that perform abortions meet two specifications to retain their licenses: (1) the location must have “hospital-like standards” regarding the layout of the building and the equipment used, and (2) the doctors must have “admitting privileges” at a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic to prove that they are fully licensed physicians. The ruling of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern PA v. Casey had created a precedent that states are not allowed to cause women undue burdens as they seek an abortion. In regards to Texas HB2, the Supreme Court ruled that “neither of [the two] provisions offers medical benefits sufficient to justify the burdens upon access that each imposes. Each places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a previability abortion, each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access [defined in] Casey […] and each violates the Federal Constitution.”[12] This ruling ensured that states could not create extreme requirements that would deter or block women from obtaining an abortion.

Using DSRP to Examine the Abortion Debate

In Systems Thinking Made Simple, Derek and Laura Cabrera define four simple rules that are used in Systems Thinking: Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, & Perspectives (DSRP), which they argue, can be used to break a complex topic into its simplest forms.

The Distinctions rule states that “any idea or thing can be distinguished from the other ideas or things it is with.”[13] Therefore, when a distinction is made, an identity and an other are created. This tendency is important because it helps us recognize that looking at one idea automatically implies that we are not looking at other idea(s).

The Systems rule states that “any idea or thing can be split into parts or lumped into a whole.”[14] Therefore, all systems are made up of a series of parts and wholes. Examining each component and its specific role in a system allows a deeper understanding of how that system functions as a whole. The interactions and relationships between parts can determine the inner workings of the system.

The Relationships rule states that “any thing or idea can relate to other things or ideas.”[15] All relationships are built on an action and a reaction. Relationships can be causal, correlational, and directional; examining the elements of relationships can help to define what type of relationship exists between two distinct ideas or parts of a system.

Finally, the Perspectives rule states that “any thing or idea can be the point or the view of the perspective.”[16] Therefore, a perspective has two parts: what is “seen” (point) and who is the “seer” (view). It is important to realize that every idea or thing can be can be examined from many perspectives. Therefore, taking a single perspective – especially without considering other possible perspectives – creates bias.

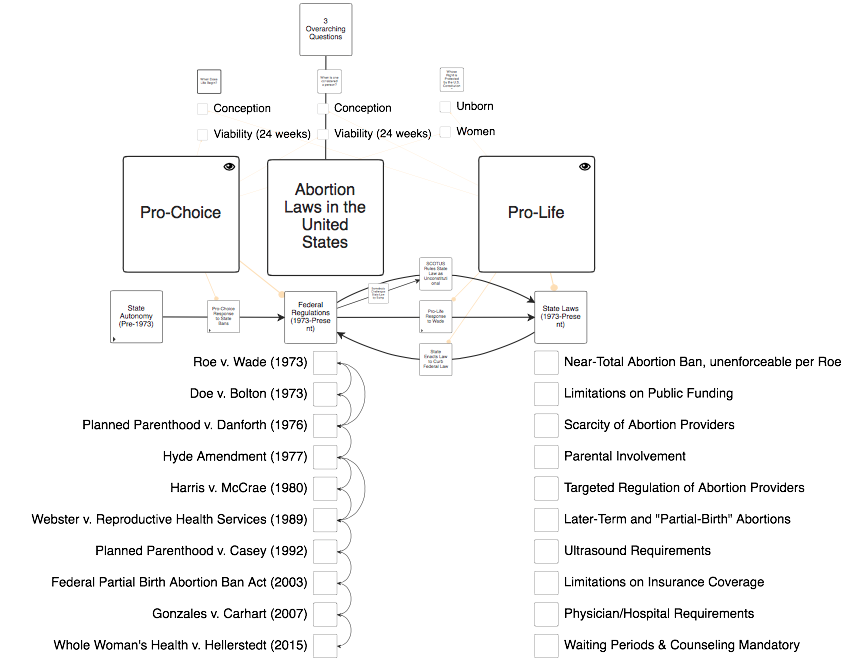

Figure 2: A metamap denoting the Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, & Perspectives of Abortion Regulations in the United States

Making Distinctions within the Abortion Debate

According to the Cabreras’ definition, distinctions allow items to be broken down into two parts – identity and other.

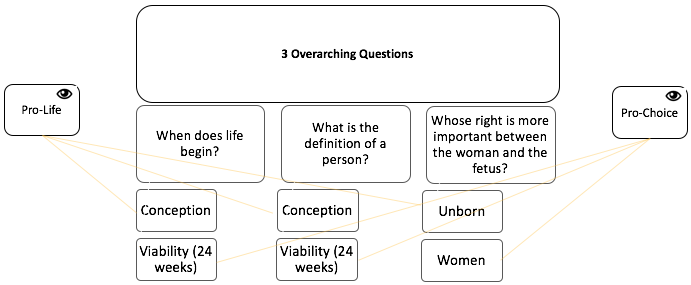

Within the abortion debate, the groups that identify with opposite sides of the argument call themselves pro-choice[17] and pro-life,[18] respectively. The use of this terminology is very strategic; by labeling oneself as “pro-choice,” there is an inherent distinction that the other side of the argument is “anti-choice.” The same can be said of the choice to label oneself “pro-life,” as it implies that if one is not for life, one must be against life, or “pro-death.” However, to make distinctions regarding the groups’ actual stances on abortion—not just the values their names imply—is to recognize that the two groups have different definitions of the terms “life,” “person,” and “rights.” The abortion debate largely surrounds three questions: (1) when does life begin? (2) what is the definition of a person? (3) whose right is more important between the woman and the fetus?

Figure 3: A look at the two perspectives in regards to the three questions.

The pro-choice side uses the definition of life laid out in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey; Roe v. Wade defined life as beginning “at the point at which the fetus becomes ‘viable’” or “potentially able to live outside the mother’s womb, albeit with artificial aid. Viability is usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks.”[19] Planned Parenthood v. Casey recalculated the timeline of viability, due to “advances in neonatal care,” to “23 or 24 weeks, or at some moment even slightly earlier in pregnancy, as it may if fetal respiratory capacity can somehow be enhanced in the future.”[20] As such, those who are pro-choice define life as starting after viability—by the distinction rule, before viability is “not life.”

The pro-life side defines life as starting with fertilization, or at conception. Therefore, those who use this distinction perceive any abortion at all to be occurring while the fetus is alive, and therefore perceive abortion to result in the death of an unborn child.[21] Those who are pro-life believe life starts at the creation of a zygote; by this definition and the distinction rule, there is no “not-life.”

Based on their distinct interpretations of the term “life,” both groups also use distinct terms for pregnancy. Those who are pro-choice use terms such as “fetus” and “embryo;” those who are pro-life use terms such as “unborn baby” and “unborn child.” When used, these terms create distinct images of what each group perceives as the target of an abortion. The use of the terms “baby” and “child” humanize the fetus, reflecting that pro-life people believe that an unborn child is a living “person” by definition.

A final term for which the two groups have different interpretations is “right.” While the definition of a right remains the same for the two groups, there is a stark difference on whose right is prioritized. For those who are pro-choice, the woman’s right to privacy, and therefore her right to choose, supersedes any rights that may belong to the fetus. For those who are pro-life, the unborn child’s right to life supersedes any rights that may belong to the woman, as they believe it is important that government give the unborn child a voice.

Perspectives in Statements Regarding Abortion

Perspective affects, among other things, the way an individual interprets the Constitution. While each lawmaker, Supreme Court Justice, and citizen of the United States may be examining the same point (the text of the Constitution), each individual also has his or her own view of that point, which is dependent on upbringing, religion, political views, etc. Therefore, by the Cabreras’ definition, every person has his or her own perspective.

In regards to the abortion debate, several important documents are used to defend both sides. The pro-choice side cites the 14th amendment to the Constitution, specifically the due process clause that implies that U.S. citizens have a right to privacy. This is the clause that was used in Roe v. Wade and granted a woman’s right to choose:

“The emphasis must be not on the right to abortion but on the right to privacy and reproductive control.” – Ruth Bader Ginsburg[22]

The pro-life side often cites the Declaration of Independence, in which all citizens are promised that “no person shall… be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of the law.”[23] Those who are pro-life believe that life starts at conception and by that definition, a fetus is considered a person.

“…the promises of the Declaration of Independence are [not] just for the strong, the independent, the healthy. They are for everyone—including unborn children.”

– George W. Bush[24]

Figure 5: President George W. Bush signs the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003.

These quotations exhibit different interpretations of the words of the Founding Fathers. While both of the documents are about the rights granted to American citizens, and therefore constitute similar points, they are examined from opposite sides of the argument—from different views.

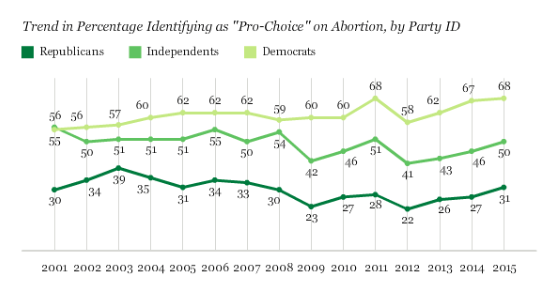

As a highly contentious political topic, legal access to abortion has been at the forefront of political debates since 1973. As demonstrated by the above quotes, there are two clear perspectives on the issue, perspectives that are often affiliated with specific political parties.[25] However, it is also important to recognize that there are a variety of points of view within the two sides.

Figure 6: A graph that represents the views of political party constituents on abortion laws.[26]

Among those who are pro-choice, there is a population that does not believe in abortion; however, they do believe that a woman—not the government—has the right to choose. Hillary Clinton, the 2016 Democratic nominee for President, described this phenomenon as follows:

“I have met thousands and thousands of pro-choice men and women. I have never met anyone who is pro-abortion. Being pro-choice is not being pro-abortion. Being pro-choice is trusting the individual to make the right decision for herself and her family, and not entrusting that decision to anyone wearing the authority of government in any regard.”[27]

There is a general belief that political party defines whether someone is pro-life or pro-choice. With this in mind, it is also important to recognize that political party affiliation does not necessarily imply which perspective someone will take on abortion. While highly correlated, neither is causal.

Systems and Relationships Define U.S. Government

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”– 10th Amendment[28]

The 10th Amendment to the United States Constitution is a provision that leaves any powers not specified as federal powers in the Constitution to be decided by each individual state.

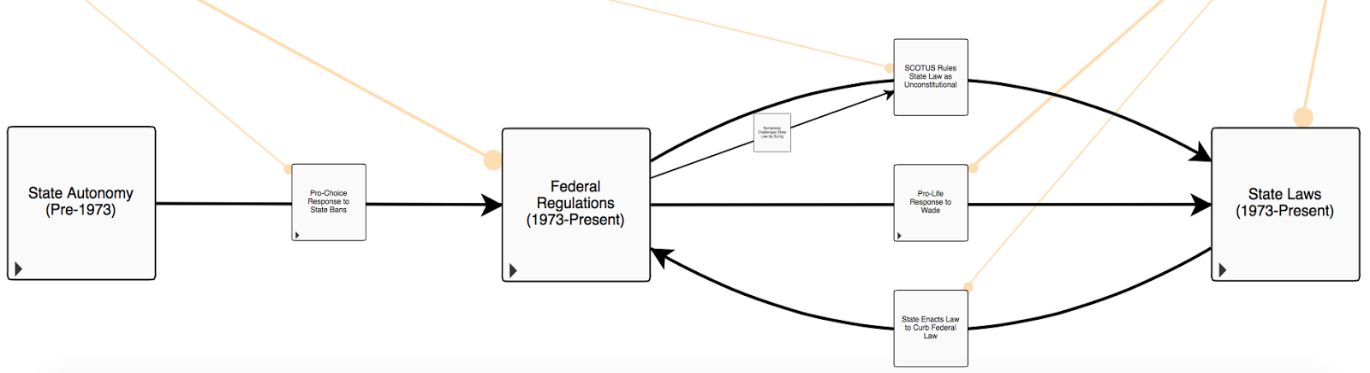

By the Cabreras’ definition, federal policy and state policy would each be parts of the whole American government system. Every law that relates to abortion—whether it be state or federal—fits under the overarching umbrella term of “Abortion Regulations in the United States.”

At the same time, by the Cabreras’ definition, there is a relationship between federal abortion policy and each state’s abortion policy. All of the states that enacted laws regulating abortions in response to the court cases outlined above did so in reaction to decisions (or actions) made by the Supreme Court.

A “State has a legitimate interest in seeing to it that abortion…is performed under circumstances that insure maximum safety for the patient” – Roe v. Wade (1973)[29]

Following the decisions of Roe v. Wade, the majority of states used the above phrase in conjunction with the 10th amendment to justify new laws that would regulate legalized abortion as much as possible.

Figure 7: A close up of the systems and relationships that define abortion regulations in the U.S.

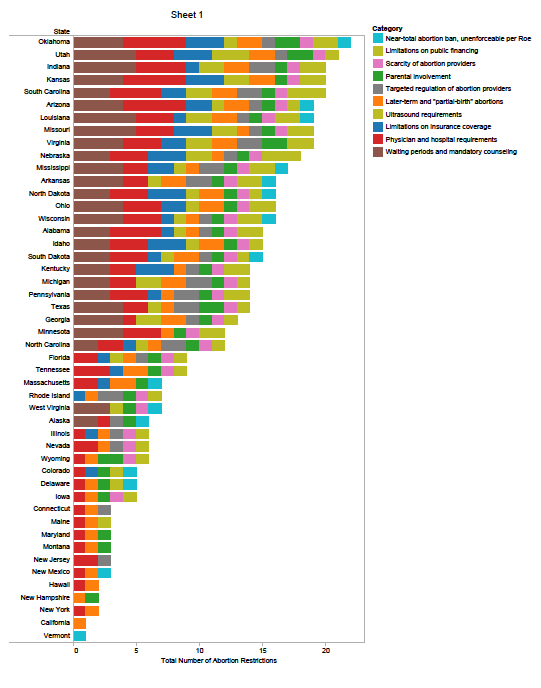

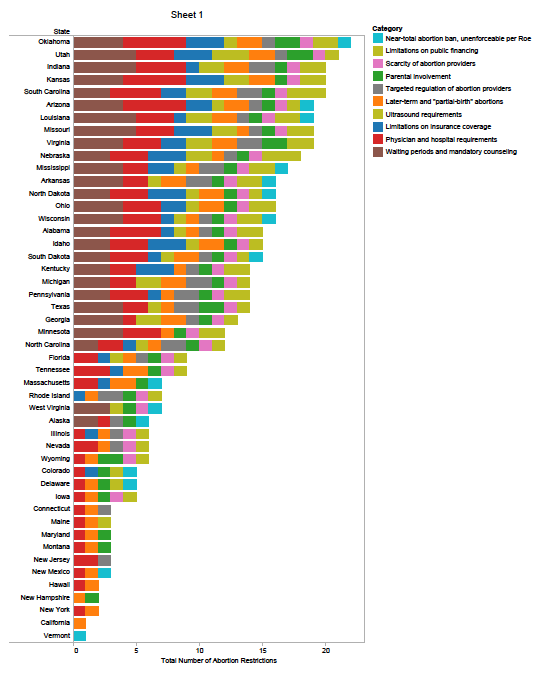

Currently, 49 states and D.C. have some form of abortion regulation. These restrictions can be grouped into ten different categories: (1) a near-total abortion ban, unenforceable per Roe v. Wade, (2) limitations on public financing, (3) scarcity of abortion providers, (4) parental involvement, (5) targeted regulation of abortion providers, (6) later-term and “partial-birth” abortion bans, (7) ultrasound requirements, (8) limitations on insurance coverage, (9) physician and hospital requirements, and (10) mandatory waiting periods and counseling.[30]

15 states have trigger laws[31] that would make abortion illegal at all points in pregnancy if the precedent set by Roe v. Wade was ever overturned.[32]

35 states have enacted limitations on public financing of abortions. These restrictions can limit state funding available to organizations for providing, counseling, or referring women to abortion services – especially for state-run agencies. Additionally, these restrictions can limit the use of public funds for abortions to cases that are a result of rape or incest or that endanger the life of the mother.

32 states and DC have a scarcity of licensed abortion clinics (defined as fewer than 10 abortion clinics in the state) due to the impact of physician, hospital, and licensing regulations.

38 states require that one or both parents be notified in the case that their minor daughter is seeking an abortion. Of these states, 25 require that one or both parents consent to the procedure before it is performed.

27 states require that facilities apply for a license to perform abortions. These licenses can be very tightly monitored and require undergoing a long, arduous process to obtain, depending on the state.

43 states ban abortions after a certain gestational threshold in the pregnancy and/or ban partial-birth abortions. These bans exist because the fetuses undergoing these procedures could be considered viable by the definitions laid down in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

24 states require an ultrasound be performed, and that the pregnant female be offered the opportunity to see the image, before undergoing the procedure.

26 states restrict insurance coverage of abortion procedures by establishing limits for private insurers, limiting coverage for public employees, and allowing insurance companies to opt out of covering the procedure.

43 states require that abortion procedures only be performed by licensed physicians and that, if occurring after a certain point in the pregnancy, the procedures be performed at a hospital. While this point in fetal development varies by state, these requirements can result in women having to travel further away from home to find a location that meets the necessary requirements.

27 states require mandatory waiting periods and counseling sessions for women wishing to have abortions. Many of these states require that a woman set up a separate counseling appointment, so that she has to return to the same location at a later date before being allowed to complete the abortion. Counseling sessions can include descriptions of fetal development, information about fetal pain, and a description of the procedure.[33]

Figure 8: A chart showing the number and types of restrictions on abortion each state has.[34]

Access to Services

As demonstrated by the contentious restrictions of the Texas HB2 law, access to abortion clinics is extremely limited in some parts of the country. While this law was overturned by the Supreme Court’s decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, it was originally enacted in 2013. During the two years it was in play, the HB2 restrictions severely limited the number of locations at which women could obtain abortions in the state of Texas; only 10 of 40+ clinics met the standards. Those 10 clinics were grouped in large metropolitan areas, leaving western Texas and the Rio Grande Valley without any licensed clinics. Currently, there is still a large scarcity of clinics in Texas—the second most populous state in the country.

Figure 9: A representation of the consequences of Texas HB2.

In addition to laws like Texas HB2, recently there has been a movement to “defund Planned Parenthood” –meaning to eliminate the federal funds that support the organization. Planned Parenthood is an organization that provides “high-quality, affordable health care for women, men and young people.”[35]

Figure 10: The Planned Parenthood logo and slogan.

In 2012, Planned Parenthood performed 327,166 abortion procedures; the Center for Disease Control reported that in that year, 699,202 legal abortions were performed in the United States.[36],[37], If both numbers are all inclusive, Planned Parenthood was responsible for providing almost 47% of abortions that year.

In 2015, Planned Parenthood was accused of selling fetal tissue and using government funding (tax dollars) to pay for the abortion procedures it performs. This information was met by national outrage despite Planned Parenthood denying the claims as it is illegal to use public dollars to pay for abortions.

If defunded, Planned Parenthood would not be able to support the same number of women, men, and children as it does today; it is possible some of its locations and/or services would be eliminated without government support. As many states already have a scarcity of abortion clinics, there is a large debate about how defunding Planned Parenthood could cause “undue burdens” on women looking to have an abortion. Additionally, abortions only make up 3% of Planned Parenthood’s annual services; closing clinics would not solely affect the number of abortions provided each year, but would also affect services including family planning and cancer screening.

The policy implications of the increasing number of bills targeting abortions are represented throughout the history of these bills and the court cases used to challenge them. As long as the divide between the pro-choice and pro-life groups continues to exist, it is very improbable that the cyclical pattern of state laws and Supreme Court decisions will end. Examining this debate through the DSRP lens eliminated the bias of each side’s point of view; a new perspective of the debate is needed in order for both sides to clearly understand the other’s argument. Creating a new perspective to frame the debate could, therefore, allow the discourse to continue without the volatility of the political rhetoric and policy cycle.

Bibliography

“abortion.” Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, 2016.

“Abortion ProCon.org.”ProConorg Headlines. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Oct. 2016.

An Overview of Abortion Laws. Guttmacher Institute. N.p., 1 Oct. 2016. Web. 3 Oct. 2016.

Cabrera L, Cabrera D. Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems.

Ithaca: Odyssean Press; 2015.

“Data and Statistics.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, 2016. Web. 2 Oct. 2016.

“George W. Bush Quote.” A-Z Quotes. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Oct. 2016.

Heimlich, R. “States with Anti-Abortion “Trigger” Laws.” Pew Research Center RSS. N.p., 2006. Web. 11

Oct. 2016.

“Hillary Clinton on Abortion.” Hillary Clinton on Abortion. N.p., 22 Jan. 1999. Web. 8 Oct. 2016

Independence Hall Association. “The Declaration of Independence.” Ushistory.org. N.p., 4 July 1995.

Web. 16 Oct. 2016.

Masci, D., Lupu, I.C., Elwood, F. and Davis, E. A History of Key Abortion Rulings of the U.S.

Supreme Court. Pew Research Center’s Religion Public Life Project RSS. N.p., 2013. Web. 1

Oct. 2016.

“‘Partial-Birth Abortion:’ Separating Fact from Spin.” NPR. NPR, 21 Feb. 2006. Web. 16 Oct. 2016.

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern PA. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

Planned Parenthood. Planned Parenthood Services. Fact Sheet. 2012.

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Wikiquote, . 27 Jul 2016, 03:39 UTC. 9 Oct. 2016.

“The Constitution of the United States,” Amendment 10.

“The Constitution of the United States,” Amendment 14.

Webber, A., Moslander, M. “Dozens of new state limits on abortions added in 2012.” Remapping

Debate. N.p., n.d. Web. (2016).

Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. ___ (2016).

Appendix

Appendix A: Abortion Restrictions by State

Source: Webber, A., Moslander, M. “Dozens of new state limits on abortions added in 2012.” Remapping Debate. N.p., n.d. Web. (2016).

Source: Webber, A., Moslander, M. “Dozens of new state limits on abortions added in 2012.” Remapping Debate. N.p., n.d. Web. (2016).

- Second-Year Fellow,Cornell University, College of Human Ecology, Cornell Institute for Public Affairs, Ithaca, NY ↑

- Correspondence: kar285@cornell.edu ↑

- Citing this Case: Reeves, K. (2016). “Choosing a Side: Examining the Abortion Debate.” Cognitive Case Study SEries. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. ↑

- Masci, D., Lupu, I.C., Elwood, F. and Davis, E. A History of Key Abortion Rulings of the U.S. Supreme Court. Pew Research Center’s Religion Public Life Project RSS. N.p., 2013. Web. 1 Oct. 2016. ↑

- “The Constitution of the United States,” Amendment 14. ↑

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↑

- Note: The definition of “viability” has changed as medical advancements are made. At the time of the Roe v. Wade ruling, viability was defined as 7 months or 28 weeks. ↑

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↑

- Parenthood of Southeastern PA. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992). ↑

- “‘Partial-Birth Abortion:’ Separating Fact from Spin.” NPR. NPR, 21 Feb. 2006. Web. 16 Oct. 2016. ↑

- Masci, D., Lupu, I.C., Elwood, F. and Davis, E. A History of Key Abortion Rulings of the U.S. Supreme Court. Pew Research Center’s Religion Public Life Project RSS. N.p., 2013. Web. 1 Oct. 2016. ↑

- Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. ___ (2016). ↑

- Cabrera L, Cabrera D. Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. Ithaca: Odyssean Press; 2015. pp. 52 ↑

- Cabrera L, Cabrera D. Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. Ithaca: Odyssean Press; 2015. pp. 52 ↑

- Cabrera L, Cabrera D. Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. Ithaca: Odyssean Press; 2015. pp. 52 ↑

- Cabrera L, Cabrera D. Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. Ithaca: Odyssean Press; 2015. pp. 52 ↑

- Note: Pro-Choice is defined as supporting the right of a woman to choose to have an abortion; supporting legalized abortion. ↑

- Note: Pro-Life is defined as supporting the right to life of the unborn fetus; opposing legalized abortion. ↑

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↑

- Parenthood of Southeastern PA. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992). ↑

- “Abortion ProCon.org.”ProConorg Headlines. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 Oct. 2016. ↑

- “Ruth Bader Ginsburg.” Wikiquote, . 27 Jul 2016, 03:39 UTC. Web. 6 Oct. 2016. ↑

- Independence Hall Association. “The Declaration of Independence.” Ushistory.org. N.p., 4 July 1995. Web. 16 Oct. 2016. ↑

- “George W. Bush Quote.” A-Z Quotes. N.p., 22 Jan. 2001 Web. 6 Oct. 2016. ↑

- Gallup, Inc. “Americans Choose “Pro-Choice” for First Time in Seven Years.” Gallup.com. N.p., 29 May 2015. Web. 16 Oct. 2016. ↑

- Gallup, Inc. “Americans Choose “Pro-Choice” for First Time in Seven Years.” Gallup.com. N.p., 29 May 2015. Web. 16 Oct. 2016. ↑

- Hillary Clinton on Abortion.” Hillary Clinton on Abortion. N.p., 22 Jan. 1999. Web. 2016 ↑

- “The Constitution of the United States,” Amendment 10. ↑

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↑

- Webber, A., Moslander, M. “Growing Set of State Abortion Restrictions Visualized.” Remapping Debate. N.p., n.d. Web. (2016). ↑

- A Trigger Law is defined as a law that is currently unenforceable but may achieve relevance and enforceability if key chances in circumstance occur. ↑

- Heimlich, R. “States with Anti-Abortion “Trigger” Laws.” Pew Research Center RSS. N.p., 2006. Web. 11 Oct. 2016. ↑

- Webber, A., Moslander, M. “Growing Set of State Abortion Restrictions Visualized.” Remapping Debate. N.p., n.d. Web. (2016). ↑

- Note: A full page, legible version of this chart can be found in the Appendix at the end of this case. ↑

- Planned Parenthood. Planned Parenthood Services. Fact Sheet. 2012. ↑

- Planned Parenthood. Planned Parenthood Services. Fact Sheet. 2012. ↑

- “Data and Statistics.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. Web. 2 Oct. 2016. ↑