Originally published June 8, 2017

By John Foote, Lecturer-Science, Technology and Infrastructure Policy, Cornell Institute for Public Affairs

Edited by Paulina Lucio Maymon

Editors’ Note: The following is the edited transcript of a talk delivered by the author to the Cornell University College of Architecture, Art, and Planning on March 10, 2017, as part of the College’s Russell Van Nest Black Lecture Series.

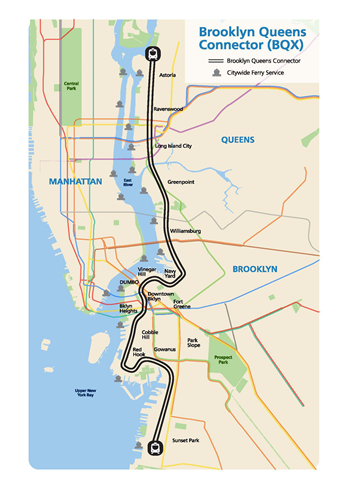

One year ago, a friend told me about a recently unveiled proposal for a new streetcar along the Brooklyn Queens waterfront in New York City. I immediately envisioned a quaint San Francisco-like trolley plying the fast-gentrifying neighborhoods along the East River. I soon learned, however, that this streetcar is a serious, ambitious, multi-billion-dollar transportation project that had the backing of a number of important individuals and organizations in New York.

As I read more about the Brooklyn Queens Connector, commonly called the BQX, I became intrigued by the scope of the project, the motivations of the City in pursuing it, and the complexities associated with implementing it. This past January I had the opportunity to lead a field project involving eleven Cornell graduate students focused on the BQX. This project entailed spending a week in New York City meeting with consultants, stakeholders, and politicians to understand the technical, social, economic and financial dimensions of the BQX. The following discussion comes out of these meetings and the subsequent analysis conducted by the student team.

The idea of reintroducing streetcars to Brooklyn after an absence of sixty years, specifically a streetcar paralleling the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront, was conceived a decade ago by the urban planner Alex Garvin in a report called “Visions for New York” (May 2006). Garvin suggested that one antidote to New York City’s Manhattan-centric transportation system which has resulted in large parts of the city being underserved and underdeveloped is a light rail train running along the waterfront corridor in Brooklyn and Queens.

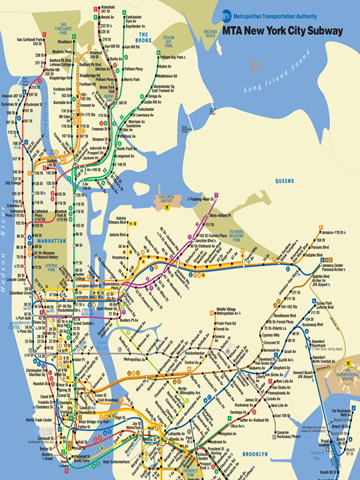

As the above MTA subway map shows, New York City’s subways reflect a classic hub and spoke pattern with lower Manhattan acting as the hub. This layout has served the City well over the last one hundred years given the Borough of Manhattan has been over that time the employment locus of the City. But according to a 2015 study conducted by the Regional Plan Association titled “Overlooked Boroughs,” over the last two decades Brooklyn and Queens have overtaken Manhattan in terms of job and population growth. This, despite the fact as noted in the RPA study, subway service is sparse in Brooklyn and Queens, bus service is slow and infrequent and the commuter rail networks bypass the outer boroughs altogether.

Garvin reintroduced his idea of a light rail train in 2013 in his contribution to “40 Ideas That Could Transform New York” sponsored by the Urban Design Forum. Then in April 2014, Michael Kimmelman, an architectural writer for The New York Times, wrote a piece titled “Imagining a Streetcar Line Along the Brooklyn to Queens Waterfront”, attributing the route to Alex Garvin.

Kimmelman observed that, “it’s easier by subway to get from Long Island City to Midtown, or from Downtown Brooklyn to Wall Street, than it is to get from housing projects in Fort Greene or Long Island City to jobs in Williamsburg, or from much of Red Hook to — well, almost anywhere.” He went on to say that “transit is about more than getting around. It maps a city’s priorities, creating a spine and a future for neighborhoods. It’s about economic as well as social mobility.”

Kimmelman went on to say, “Buses are an obvious solution. Improved bus service is an easier sell, faster to get up and running, and cheaper up front. A bus would be … fine. But where’s the romance? A streetcar is a tangible, lasting commitment to urban change. It invites investment and becomes its own attraction. I’m not talking Ye Olde Trolley. This is transit for New Yorkers who can’t wait another half-century for the next subway station.”

Kimmelman’s article sparked discussion among the real estate developers active along the Brooklyn Queens waterfront corridor, including the developer, Two Trees. Two Trees has been a key player in the renaissance of DUMBO neighborhood of Brooklyn and is currently engaged in transforming the former Domino Sugar factory site in Brooklyn on the East River into a mixed-use community. Under the leadership of Two Trees CEO Jed Walentas, a group composed primarily of representatives of the real estate community was formed to develop and promote Kimmelman’s streetcar idea. This group called itself “Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector” (Friends) and it retained consultants in various disciplines including engineering, planning, and finance to flesh out what such a streetcar would look like, how it would work and plot a proposed route. In the fall of 2015 Friends issued to a glossy and comprehensive two-hundred-page report (referred to as the Friends’ report) describing their idea.

The hope was that Friends’ report would get the attention of the De Blasio Administration, which was just finishing its second year, in order to start a discussion about improving transit along the waterfront. To the Friends’ surprise and delight the report not only caught the attention of the Mayor but also was embraced by him. In his February 2016 State of the City remarks the Mayor said:

Today we take the next great step in connecting New Yorkers to the heart of our New Economy for New York.

We’re now seeing explosive growth on the waterfront in Brooklyn and Queens. The neighborhoods that run along the East River from northern Queens to Sunset Park are home to over 400,000 people, including over 40,000 New York City Housing Authority residents; and major employment hubs like Downtown Brooklyn, the Navy Yard, and the Sunset Park industrial cluster.

So tonight I am announcing the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, a state-of-the-art streetcar that will run from Astoria to Sunset Park and has the potential to generate over $25 billion of economic impact for our city over 30 years.

The BQX has the potential to change the lives of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers.

Following that soaring rhetoric, De Blasio instructed his administration to commence a “rapid assessment” of the project described in the Friends’ report, and in April 2016 the City issued its own report that validated the concept of the BQX. This validation set in motion a long and complicated process to prepare detailed plans for the streetcar, and start the review process that includes a City Environmental Quality Review and the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure.

The stated objectives of the BQX according to the City’s Economic Development Corporation’s website are:

- Provide affordable and convenient transit for communities with limited transportation options;

- Support growing neighborhoods;

- Increase access to quality jobs;

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions; and

- Calm traffic in pursuit of the City’s Vision Zero goal of no traffic fatalities.

The proposed design to achieve these goals is a state-of-the-art-streetcar that will run north-south on fixed rails along a seventeen-mile corridor with stops approximately one-half mile apart. During peak hours, the streetcar will have five- to ten-minute headways (the time between successive streetcars). It will operate in a dedicated right of way to the extent possible, but it will interact with both vehicular and pedestrian traffic at intersections.

Also, it is important to note that the BQX is a City project and not a Metropolitan Transportation Authority project. The MTA which operates the subways and buses in New York City is a state agency and at this point, MTA leadership has expressed little interest in the BQX. During our week in New York, we heard from some observers of the New York City political scene that the BQX is an opportunity for Mayor De Blasio, who has a competitive and contentious relationship with Governor Cuomo, to complete a major piece of transportation infrastructure under the governor’s nose. That said, at some point the mayor and the governor will need to cooperate if the BQX is to become a reality given a critical element of the BQX is an integrated fare system with MTA subway and bus system. This integration will allow the MTA’s MetroCard to be accepted on BQX streetcars and permit free transfers between the BQX and the MTA subway and bus system. There certainly is a way to accomplish this integration—the question is, is there the political motivation to do it?

The Friends, before settling on a streetcar solution, evaluated bus rapid transit and light rail as possible modes. According to the Friend’s report, the streetcar alternative was chosen because it scales well to both expected ridership and the geometry of the route and because of its rider amenities. Streetcars are also fast enough to make a measurable difference in commuters’ travel times. And, urban planners believe that streetcars, because they are a permanent part of the streetscape (as opposed to buses), offer an opportunity to reshape the look and feel of the urban architecture along the corridor.

The projected capital cost of the project today is $2.5 billion. While this estimate has been reviewed by various parties, there are a number of risks that could cause this estimate to increase significantly. Foremost of these risks is the long and complicated construction period, estimated to be five years beginning in 2019, with a number of unknown conditions. One of these unknown conditions is the underground utilities which will need to be relocated as part of the route construction. Another unknown is what is entailed in building two bridges over waterways that are Superfund sites. Operating costs are also a risk; like most transit properties farebox revenues will not cover operating and maintenance costs and therefore the BQX will require an operating subsidy from the City. The amount of this subsidy is largely dependent on ridership which itself is an unknown.

While the mayor has endorsed the project and is devoting significant resources to move it through the review and approval process, not everyone in New York City is a fan of the BQX. Arguments against the BQX include:

- It is an expensive solution in a period of constrained resources;

- It is likely to attract low ridership—25,000 riders daily at the start of operations and growing to 50,000 riders daily (to put this in context, MTA subways carry 5.7 million riders daily);

- It is not part of an overall transportation plan or network, and, prior to its conception, was not on the City’s or the MTA’s priority list of transportation investments;

- It may have the effect of displacing low-income residents by accelerating the increase in property values and rents; and

- It is both a tool and subsidy for real estate developers.

With respect to the last point, one of the questions that crystallized during our week in New York is whether BQX is a transit project or a real estate project. The answer to this question matters, if for no other reason than how it affects the optics of the project. To phrase the question another way, should public dollars be spent to benefit real estate developers?

In our discussions in New York, we heard this question debated various ways. We heard that the BQX will address significant and limiting transit deficiencies in the corridor and will connect people with employment, educational and recreational opportunities. We also heard from some in the community that the real objective of BQX is to promote real estate development along the corridor. People in this camp point to Kimmelman’s 2014 article which describes the Brooklyn Queens streetcar as development-oriented transit.

This real estate orientation is also highlighted in the chapter on costs and benefits in the Friends’ report. As part of the planning of new transportation projects, it is customary to conduct a cost-benefit analysis. The most important benefits are typically those that accrue to the rider—travel time and dollar savings, convenience, and safety—as well as environmental benefits resulting from fewer cars and lessened congestion. The cost-benefit study in the Friends’ report, however, did not measure these benefits but instead calculated the projected increase in real estate values along the corridor. These increases in property values are often seen accompanying transit investments and, in the case of the BQX, the present value of the incremental property taxes realized over a forty-year period was projected to exceed the capital costs of the project.

Most transportation planners would say this is all well and good, but they also would want to know whether the project meets the transit needs of the public as measured by rider benefits and at what monetary and nonmonetary costs. The consultant who prepared the cost-benefit chapter of the Friends’ report makes reference to these rider benefits in a footnote that states: “Increases in property values associated with transportation improvements can be viewed as the capitalized ridership benefits associated with the improvement.”

While the above statement is consistent with classical transport economics which argues there that transportation costs savings (including time) is reflected in the value of real estate, one of the tasks that arose out of our week in New York is to test whether this equation holds for this project. If it does, then asking whether BQX is a transit project or a real estate project is a false choice—it can be both at the same time. That said, it is incumbent on the City to analyze projected ridership of the BQX and establish measures of rider benefits in order to marshal public support for this project. We were told that this analysis is in process.

The charge I gave to the student team was to identify the benefits that would motivate the key decision makers—the Mayor and the six City Councilmen in whose districts the BQX traverses—to greenlight the BQX. I also asked the team to identify the key challenges the project faces and the strategies that could and should be employed to address these challenges. Their findings are below.

First, the benefits: The team determined that the main benefits of the BQX are three:

- The impact the BQX will have on economic growth in the corridor measured primarily in terms of job growth;

- Improved mobility and accessibility in areas of Brooklyn and Queens, specifically the waterfront corridor, that currently have limited transportation options; and

- The positive impact on the streetscape measured in terms of improvements in pedestrian and vehicular safety.

During our week in New York, we began to appreciate the complexities of executing a major public works project, particularly in an environment as challenging as New York City. While there are numerous hurdles facing the implementation of the BQX, the student team agreed that there were four issues that should be addressed as early as possible in the planning stage.

The first issue is characterized by the value-laden word “gentrification”. Anyone who has visited certain parts of Brooklyn and Queens in the last five years can attest to dramatic changes, particularly in the waterfront communities. These changes include new office buildings, condominiums, re-purposed industrial sites, and parks and open space. That said, as we took a bus tour along the entire seventeen-mile alignment, we went through neighborhoods that look much the same as they did fifty years ago.

While the BQX may accelerate the gentrification of the already-changing neighborhoods, it is in these other, more traditional neighborhoods where the BQX could precipitate fundamental changes in demographic and socioeconomic makeup. These changes are due in large part to increasing property values spurred by the BQX and it is in these neighborhoods where there is likely to be community resistance to the project. The team agreed that gentrification should not deter the implementation of the BQX, but that the possible demographic and socio-economic changes brought about by the BQX should motivate planners to be proactive in calling for affordable and inclusionary housing.

The second issue is integration with the MTA allowing BQX to operate as a part of a larger transportation network dominated by MTA subways and buses. This needs to be a consideration in the final alignment of the BQX route so that the streetcar stops are in easy proximity to MTA subway stations and bus lines. Integration also entails a common fare system that supports the existing MetroCard—and free transfers from the BQX to MTA services and vice versa. This fare integration will require cooperation between the City and the MTA.

The third issue is short and long-term traffic and parking disruptions. One of the project’s objectives is to decrease the density of car traffic in the corridor. It is conventional wisdom that, for the BQX to deliver a quality—that is, fast—service, it will need to operate along a dedicated right of way. This will necessarily displace cars and trucks, and this loss of street capacity will have significant effects on traffic. Local businesses and residents in nearby areas may receive a spillover of vehicles that are displaced from the alignment. Further, during construction of the project, vehicular traffic, including buses, will be significantly and adversely affected. The team felt that a carefully constructed, and, even more important, a well-articulated mitigation plan is critical.

The final issue has nothing to do with the physical attributes of the project, and everything to do with the process. As I mentioned earlier, BQX has been actively promoted by the real estate community. While the transportation impacts of the BQX are tangible and significant, the debate is colored by the perception that it is a developer-oriented project.

Further, even though the City has taken on responsibility for the project, including community outreach, the Friends—which has diversified to include a broad representation of stakeholders—continues to actively promote the project. This has led to different and uncoordinated stakeholder engagement strategies being pursued by the City and the Friends, respectively. The team suggests that a more transparent communications approach is required—one that is focused on all of the intended and unintended benefits and costs, associated with the project, including the costs of the mitigation strategies mentioned earlier. And while it would be unrealistic to expect that every resident and every neighborhood in the corridor will benefit equally, if the overall benefits exceed the costs, strategies can be identified to compensate in an appropriate way the people who are left out.

In two years the BQX has made impressive progress, but it still has a long way to go in uncertain times; the review process in New York City is daunting, there is a mayoral election later this year, the governor and the mayor are not speaking with each other, and communities along the corridor are taking closer notice of the project. This last point is perhaps the most important: A project of this size and scope is going to require the people and communities affected to be on board.

The last meeting we had during our week in New York was with Sam Schwartz, a former NYC Traffic Commissioner and now the principal in a transportation engineering firm. Over his forty-five-year career, Gridlock Sam, as he is known, has seen and been involved in hundreds of transportation projects. Based on his experience, Sam offered up a piece of homespun wisdom. It was, “losers yell louder than winners sing.” We took away from the week in New York the realization that there are many questions to be answered before we hear the bell of the BQX.

Acknowledgements—The student team that did much of the hard work that formed the basis for the above talk was composed of the following individuals: Yunie Chang MPA ’18, Carolina Araya Chaves MPA ’18, Joy Das MPA ’18, Daniel De La Hormaza MPA ’18, Jairo Mena-Arce MPA ’18, Molly Warrington MPA ’18, Ashley Pryce MRP ’18, Ingvild Roald MRP ’17, Michael Seo MRP ’17, Jiayun Sun MS-Engr ’17, and Tomohiko Watanabe MPA ’18.